Stephen A. Douglas

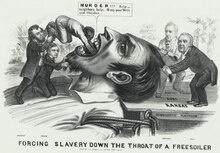

Though Douglas had hoped the Kansas–Nebraska Act would ease sectional tensions, it elicited a strong reaction in the North and helped fuel the rise of the anti-slavery Republican Party.

During the Lincoln–Douglas debates, Douglas articulated the Freeport Doctrine, which held that territories could effectively exclude slavery despite the Supreme Court's ruling in the 1857 case of Dred Scott v. Sandford.

Years later he said, "I found my mind liberalized and my opinions enlarged when I got on these broad prairies, with only the heavens to bound my vision, instead of having them circumscribed by the little ridges that surrounded the valley where I was born."

During one of his first campaign appearances outside of Illinois, Douglas denounced high tariff rates, saying that they constituted "an act for the oppression and plunder of the American laborer for the benefit of a few large capitalists".

[19] Douglas strongly supported the annexation of Texas, and in May 1846 he voted to declare war on Mexico after U.S. and Mexican forces clashed near the Rio Grande River.

[28] He also descends from Wilbore's son, Samuel Wilbur, Jr. who was mentioned by name in the Royal Charter of 1663, and who, with Porter, was an original purchaser of the Pettaquamscutt lands that became the town of South Kingstown, Rhode Island.

[36] The compromise faced strong opposition from Northerners like William Seward, who favored the Wilmot Proviso and attacked the fugitive slave provision, and Southerners like John C. Calhoun, who opposed the creation of new free states.

[40] Douglas' role in passing the compromise gave him the stature of a national leader, and he enjoyed the support of the Young America movement, which favored expansionary policies.

[43] Returning to the Senate in late 1853, Douglas initially sought to avoid taking center stage in national debates, but he once again became involved in sectional disputes stemming from the issue of slavery in the territories.

In order to provide for western expansion and the completion of a transcontinental railroad, Douglas favored incorporating parts of the vast unorganized territory located west of the Missouri River and east of the Rocky Mountains.

Opponents of popular sovereignty attacked its supposed fairness; Abraham Lincoln claimed that Douglas "has no very vivid impression that the Negro is human; and consequently has no idea that there can be any moral question in legislating about him".

Buchanan dominated in the South, but Frémont won several Northern states and Douglas ally William Alexander Richardson lost the 1856 Illinois gubernatorial election.

[56] Shortly after Buchanan took office, the Supreme Court issued the Dred Scott decision, which declared that slavery could not be legally excluded from the federal territories.

Though the ruling was unpopular with many in the North, Douglas urged Americans to respect it, saying "whoever resists the final decision of the highest judicial tribunal aims a deadly blow at our whole republican system of government."

He approved of another aspect of the ruling, which held that African-Americans could not be citizens, stating that the Founding Fathers "referred to the white race alone, and not the African, when they declared men to have been created free and equal".

Those police regulations can only be established by the local legislature; and if the people are opposed to slavery, they will elect representatives to that body who will by unfriendly legislation effectually prevent the introduction of it into their midst."

[65] Lincoln disclaimed the radical-for-the-time views on racial equality attributed to him by Douglas, arguing only for the right of African Americans to personal liberty and to earn their own livings.

"[69] According to the Springfield Republican, in 1857 Douglas "was, next to General Cass, the richest man in public life"; by the end of 1859, after extravagant political spending and disappointing investments, he was near bankrupt.

"Two months ago [before John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry] he seemed to have more political power and popularity than any other American; everybody was talking about him, and his chances for the Presidency were hopefully discussed by his friends, and reluctantly conceded by his enemies—but now ... the Southern Democracy have ceased to fear him; and the Northern to worship him."

Douglas helped defeat an attempt to pass a federal slave code, but saw his own bill to establish agricultural land-grant colleges vetoed by Buchanan.

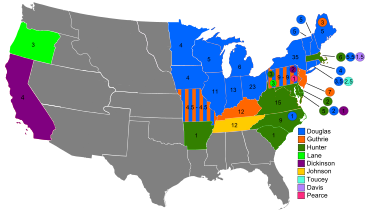

[74] After a contentious battle over the inclusion of popular sovereignty or a federal slave code in the party platform, several Southern delegations walked out of the convention.

The convention subsequently held several rounds of presidential balloting, and while Douglas received by far the most support of any of the candidates, he fell well short of the necessary two-thirds majority of delegates.

[75] In the weeks leading up to second Democratic convention, a group of former Whigs and Know Nothings formed the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell for president.

[citation needed] The 1860 Republican National Convention passed over the initial front-runner, William Seward, and nominated Douglas' old opponent, Abraham Lincoln.

[85] [James Buchanan] remarked to him [Douglas] that it was very perilous for a public man to put himself in opposition to his party—and that he must take the liberty of reminding him of the fate of Rives and Tallmadge, who rebelled against the policy of Gen. Jackson.

He joined a special committee of thirteen senators, led by John J. Crittenden, which sought a legislative solution to the growing sectional tensions between the North and South.

The next day, on June 4, Secretary of War Simon Cameron issued a circular to Union armies, announcing "the death of a great statesman ... a man who nobly discarded party for his country".

[citation needed] Graham Peck finds that while several scholars have said that Douglas was personally opposed to slavery despite owning a plantation in Mississippi, none has presented "extensive arguments to justify their conclusion".

"[102] However, though he "privately deplored slavery and was opposed to its expansion (and, indeed, in 1860 was widely regarded in both North and South as an antislavery candidate), he felt that its discussion as a moral question would place it on a dangerous level of abstraction.

Numerous places have been named after him: counties in Colorado, Georgia,[107] Illinois, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, Oregon, South Dakota, Washington and Wisconsin.