Steppe Route

Hippocrates reflected on the impact of climatic changes, on subsistence, and advanced the idea of their influence on the organisation of human communities, as an explanation to populations migration.

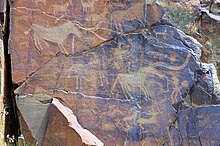

In the absence of discovered written language records from early Eurasian nomads, it is difficult to determine how they referred to themselves, and the various earliest cultures along the Steppe Road are mostly identified by distinctive burial arrangements and delicate artifacts.

The nomadic practices of herding and simultaneously farming, in which horse-riding warfare practised by an elite played a central role[7] spread in the area from around 1000 BCE.

French historian Fernand Braudel saw the presence of pastoral nomads as a disruptive force often interrupting periods of slow historical processes, allowing for rapid change and cultural oscillation.

Newly studied archaeological sites such as Berel[10] in Kazakhstan, an elite burial ground of the Pazyryk culture located near the borders with Russia, Mongolia, and China at the junction of the Altai and Tarbagatai mountains along the Kara-Kaba River, showed that much work still needs to be performed to better understand the communities bordering this intercultural transportation route and to assess unexcavated sites in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan.

The work confirmed that the semi-nomadic groups of the late fourth and early third centuries BCE, known to Herodotus as the Arimaspians, were not only breeding horses for trade.

Fossils excavated in Mount Carmel, Israel in 2002, show that Homo sapiens arrived earlier than previously thought at the gate of the Steppe Route 194,000–177,000 years ago and possibly interbred with Neanderthals who inhabited some parts of Eurasia.

Pastoralism introduced a major leap in social development and prepared the necessary base for the creation of ancient semi-nomadic states along the Eurasian Steppe Route.

[13] The analysis of carbon and nitrogen isotopes in skeletal collagen of these same human remains has helped to classify their dietary background and to characterize the economy of the steppe communities.

The earliest evidence for riding comes from the Sredny Stog communities of eastern Ukraine and from south Russia with the domestication of the Bactrian camel[17] dating to c. 4000 BCE.

[18] In western Eurasia, the revolutionary introduction of writing, dated to the same period, apparently originated to serve accounting needs but developed with the Sumerian concern to leave messages for the afterlife.

[19][20] In Inner China, which represented about half of the territory of the modern Chinese state (i.e., excluding Manchuria, Mongolia, Xinjiang and the Qinghai-Tibet plateau,[21] there have been discoveries of tortoise-shell carvings of Jiahu symbols dating back to c. 6200-6600 BCE.

[22] Writing and accounting likely started independently in various areas of Eurasia, including the Mediterranean Basin and Mesopotamia, but they appear to have spread relatively rapidly along the Steppe Route.

The dual use of a prehistoric cavalry and metal weapons probably laid the framework of a much more militarized and possibly more hostile environment, triggering the migration of the most peaceful - or weakest - Homo sapiens populations to more remote parts of the Steppe route.

[25] Economic prosperity led to an exceptional richness of artistic expression that was to be found in the smaller forms, particularly in painted ceramics, small carved objects, ornaments inspired by wildlife, and funerary gifts.

During this time, Karasuk-style bronzeware spread not only to the Upper Xiajadian, but also to North Korea, the Liaoning area, and the far eastern region of Russia (Primorisky).

Slow-moving groups following a heavy chariot with four solid wheels led by hunters and fishermen were gradually replaced or enslaved by herdsmen from the steppes and semi-deserts.

Nomads rode small horses and knew how to fight from horseback, primarily with a bow that was the distinctive weapon from the steppe and sometimes even with a sword or a saber when the rider was more affluent.

[9] Members of these mobile, energetic and resourceful communities used light war-chariots with wheels having a diameter up to one meter with 10 spokes and drawn by horses,[30] The pattern spread in many different directions and strengthened an already-robust system of vigorous and widespread exchanges within and sometimes beyond the inner Eurasian steppes.

[2] Various artifacts, including glassware, excavated from tombs in the Korean kingdom of Silla were similar to those found in the Mediterranean part of the Roman Empire, showing that exchange did take place between the two extremities of the steppe road.

[17] The influences that had traveled along the Steppe Route from the Mediterranean to the Korean Peninsula can be seen in similar techniques, styles, cultures, religions, and even disease patterns.