Stereoscopy

The most notable difference is that, in the case of "3D" displays, the observer's head and eye movement do not change the information received about the 3-dimensional objects being viewed.

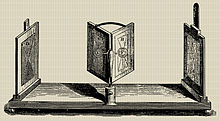

[10] Wheatstone originally used his stereoscope (a rather bulky device)[11] with drawings because photography was not yet available, yet his original paper seems to foresee the development of a realistic imaging method:[12] For the purposes of illustration I have employed only outline figures, for had either shading or colouring been introduced it might be supposed that the effect was wholly or in part due to these circumstances, whereas by leaving them out of consideration no room is left to doubt that the entire effect of relief is owing to the simultaneous perception of the two monocular projections, one on each retina.

But if it be required to obtain the most faithful resemblances of real objects, shadowing and colouring may properly be employed to heighten the effects.

Careful attention would enable an artist to draw and paint the two component pictures, so as to present to the mind of the observer, in the resultant perception, perfect identity with the object represented.

[14] Solving the Correspondence problem in the field of Computer Vision aims to create meaningful depth information from two images.

This "false dimensionality" results from the developed stereoacuity in the brain, allowing the viewer to fill in depth information even when few if any 3D cues are actually available in the paired images.

However, any viewing aid that uses prisms, mirrors or lenses to assist fusion or focus is simply a type of stereoscope, excluded by the customary definition of freeviewing.

An autostereogram is a single-image stereogram (SIS), designed to create the visual illusion of a three-dimensional (3D) scene within the human brain from an external two-dimensional image.

Head-mounted displays may also be coupled with head-tracking devices, allowing the user to "look around" the virtual world by moving their head, eliminating the need for a separate controller.

Performing this update quickly enough to avoid inducing nausea in the user requires a great amount of computer image processing.

Owing to rapid advancements in computer graphics and the continuing miniaturization of video and other equipment these devices are beginning to become available at more reasonable cost.

Additionally, technical data and schematic diagrams may be delivered to this same equipment, eliminating the need to obtain and carry bulky paper documents.

As of 2013, the inclusion of suitable light-beam-scanning means in a contact lens is still very problematic, as is the alternative of embedding a reasonably transparent array of hundreds of thousands (or millions, for HD resolution) of accurately aligned sources of collimated light.

The main drawback of active shutters is that most 3D videos and movies were shot with simultaneous left and right views, so that it introduces a "time parallax" for anything side-moving: for instance, someone walking at 3.4 mph will be seen 20% too close or 25% too remote in the most current case of a 2x60 Hz projection.

Anaglyph 3D is the name given to the stereoscopic 3D effect achieved by means of encoding each eye's image using filters of different (usually chromatically opposite) colors, typically red and cyan.

The advantage of this technology consists above all of the fact that one can regard ChromaDepth pictures also without eyeglasses (thus two-dimensional) problem-free (unlike with two-color anaglyph).

[23] The Pulfrich effect is based on the phenomenon of the human eye processing images more slowly when there is less light, as when looking through a dark lens.

The optics split the images directionally into the viewer's eyes, so the display viewing geometry requires limited head positions that will achieve the stereoscopic effect.

[citation needed] It creates a light field identical to that which emanated from the original scene, with parallax about all axes and a very wide viewing angle.

Unfortunately, this "pure" form requires the subject to be laser-lit and completely motionless—to within a minor fraction of the wavelength of light—during the photographic exposure, and laser light must be used to properly view the results.

Although the original photographic processes have proven impractical for general use, the combination of computer-generated holograms (CGH) and optoelectronic holographic displays, both under development for many years, has the potential to transform the half-century-old pipe dream of holographic 3D television into a reality; so far, however, the large amount of calculation required to generate just one detailed hologram, and the huge bandwidth required to transmit a stream of them, have confined this technology to the research laboratory.

In 2013, a Silicon Valley company, LEIA Inc, started manufacturing holographic displays well suited for mobile devices (watches, smartphones or tablets) using a multi-directional backlight and allowing a wide full-parallax angle view to see 3D content without the need of glasses.

An infrared laser is focused on the destination in space, generating a small bubble of plasma which emits visible light.

This is achieved by using an array of microlenses (akin to a lenticular lens, but an X–Y or "fly's eye" array in which each lenslet typically forms its own image of the scene without assistance from a larger objective lens) or pinholes to capture and display the scene as a 4D light field, producing stereoscopic images that exhibit realistic alterations of parallax and perspective when the viewer moves left, right, up, down, closer, or farther away.

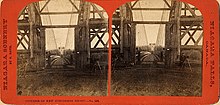

Found in animated GIF format on the web, online examples are visible in the New-York Public Library stereogram collection Archived 25 May 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

The entire scene, including the window, can be moved backwards or forwards in depth, by horizontally sliding the left and right eye views relative to each other.

The images can be cropped creatively to create a stereo window that is not necessarily rectangular or lying on a flat plane perpendicular to the viewer's line of sight.

Other stereo artists include Zoe Beloff, Christopher Schneberger, Rebecca Hackemann, William Kentridge, and Jim Naughten.

[34] The ability to create realistic 3D images from a pair of cameras at roughly human-height gives researchers increased insight as to the nature of the landscapes being viewed.

The same technique can also be applied to any mathematical (or scientific, or engineering) parameter that is a function of two variables, although in these cases it is more common for a three-dimensional effect to be created using a 'distorted' mesh or shading (as if from a distant light source).

3D red cyan

glasses are recommended to view this image correctly.

3D red cyan

glasses are recommended to view this image correctly.

3D red cyan

glasses are recommended to view this image correctly.

3D red cyan

glasses are recommended to view this image correctly.