Stern–Gerlach experiment

In quantum physics, the Stern–Gerlach experiment demonstrated that the spatial orientation of angular momentum is quantized.

In the original experiment, silver atoms were sent through a spatially-varying magnetic field, which deflected them before they struck a detector screen, such as a glass slide.

The screen revealed discrete points of accumulation, rather than a continuous distribution,[1] owing to their quantized spin.

Historically, this experiment was decisive in convincing physicists of the reality of angular-momentum quantization in all atomic-scale systems.

[2][3][4] After its conception by Otto Stern in 1921, the experiment was first successfully conducted with Walther Gerlach in early 1922.

[1][5][6] The Stern–Gerlach experiment involves sending silver atoms through an inhomogeneous magnetic field and observing their deflection.

The laws of classical physics predict that the collection of condensed silver atoms on the plate should form a thin solid line in the same shape as the original beam.

However, the inhomogeneous magnetic field caused the beam to split in two separate directions, creating two lines on the metallic plate.

The results show that particles possess an intrinsic angular momentum that is closely analogous to the angular momentum of a classically spinning object, but that takes only certain quantized values.

The experiment is normally conducted using electrically neutral particles such as silver atoms.

This avoids the large deflection in the path of a charged particle moving through a magnetic field and allows spin-dependent effects to dominate.

If it moves through a homogeneous magnetic field, the forces exerted on opposite ends of the dipole cancel each other out and the trajectory of the particle is unaffected.

Each particle would be deflected by an amount proportional to the dot product of its magnetic moment with the external field gradient, producing some density distribution on the detector screen.

[9] Although some discrete quantum phenomena, such as atomic spectra, were observed much earlier, the Stern–Gerlach experiment allowed scientists to directly observe separation between discrete quantum states for the first time.

If the experiment is conducted using charged particles like electrons, there will be a Lorentz force that tends to bend the trajectory in a circle.

This force can be cancelled by an electric field of appropriate magnitude oriented transverse to the charged particle's path.

Therefore, the measurement yields only the squared magnitudes of the constants, which are interpreted as probabilities.

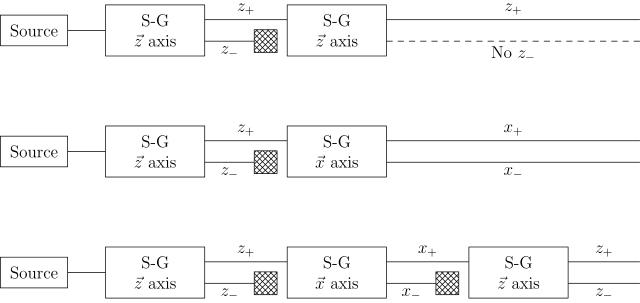

If we link multiple Stern–Gerlach apparatuses (the rectangles containing S-G), we can clearly see that they do not act as simple selectors, i.e. filtering out particles with one of the states (pre-existing to the measurement) and blocking the others.

In the figure below, x and z name the directions of the (inhomogenous) magnetic field, with the x-z-plane being orthogonal to the particle beam.

[11] The Stern–Gerlach experiment was conceived by Otto Stern in 1921 and performed by him and Walther Gerlach in Frankfurt in 1922.

[10] At the time of the experiment, the most prevalent model for describing the atom was the Bohr-Sommerfeld model,[12][13] which described electrons as going around the positively charged nucleus only in certain discrete atomic orbitals or energy levels.

The Stern–Gerlach experiment was meant to test the Bohr–Sommerfeld hypothesis that the direction of the angular momentum of a silver atom is quantized.

[14] The experiment was first performed with an electromagnet that allowed the non-uniform magnetic field to be turned on gradually from a null value.

[1] When the field was null, the silver atoms were deposited as a single band on the detecting glass slide.

Note that the experiment was performed several years before George Uhlenbeck and Samuel Goudsmit formulated their hypothesis about the existence of electron spin in 1925.

[18] However, in 1926 the non-relativistic scalar Schrödinger equation had incorrectly predicted the magnetic moment of hydrogen to be zero in its ground state.

To correct this problem Wolfgang Pauli considered a spin-1/2 version of the Schrödinger equation using the 3 Pauli matrices which now bear his name, which was later shown by Paul Dirac in 1928 to be a consequence of his relativistic Dirac equation.

In the early 1930s Stern, together with Otto Robert Frisch and Immanuel Estermann improved the molecular beam apparatus sufficiently to measure the magnetic moment of the proton, a value nearly 2000 times smaller than the electron moment.

In 1931, theoretical analysis by Gregory Breit and Isidor Isaac Rabi showed that this apparatus could be used to measure nuclear spin whenever the electronic configuration of the atom was known.

[22] The Stern–Gerlach experiment was the first direct evidence of angular-momentum quantization in quantum mechanics,[23] and it strongly influenced later developments in modern physics: