Paddle steamer

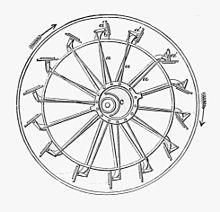

The outer edge of the wheel is fitted with numerous, regularly spaced paddle blades (called floats or buckets).

More advanced paddle-wheel designs feature "feathering" methods that keep each paddle blade closer to vertical while in the water to increase efficiency.

Though the side wheels and enclosing sponsons make them wider than sternwheelers, they may be more maneuverable, since they can sometimes move the paddles at different speeds, and even in opposite directions.

European sidewheelers, such as PS Waverley, connect the wheels with solid drive shafts that limit maneuverability and give the craft a wide turning radius.

Most were built with inclined steam cylinders mounted on both sides of the paddleshaft and timed 90 degrees apart like a locomotive, making them instantly reversing.

The first mention of paddle wheels as a means of propulsion comes from the fourth– or fifth-century military treatise De Rebus Bellicis (chapter XVII), where the anonymous Roman author describes an ox-driven paddle-wheel warship: Animal power, directed by the resources on ingenuity, drives with ease and swiftness, wherever utility summons it, a warship suitable for naval combats, which, because of its enormous size, human frailty as it were prevented from being operated by the hands of men.

[6]Italian physician Guido da Vigevano (circa 1280–1349), planning for a new crusade, made illustrations for a paddle boat that was propelled by manually turned compound cranks.

[7] One of the drawings of the Anonymous Author of the Hussite Wars shows a boat with a pair of paddlewheels at each end turned by men operating compound cranks.

[8] The concept was improved by the Italian Roberto Valturio in 1463, who devised a boat with five sets, where the parallel cranks are all joined to a single power source by one connecting rod, an idea adopted by his compatriot Francesco di Giorgio.

[8] In 1539, Spanish engineer Blasco de Garay received the support of Charles V to build ships equipped with manually-powered side paddle wheels.

From 1539 to 1543, Garay built and launched five ships, the most famous being the modified Portuguese carrack La Trinidad, which surpassed a nearby galley in speed and maneuverability on June 17, 1543, in the harbor of Barcelona.

[9] 19th century writer Tomás González claimed to have found proof that at least some of these vessels were steam-powered, but this theory was discredited by the Spanish authorities.

[10] In 1787, Patrick Miller of Dalswinton invented a double-hulled boat that was propelled on the Firth of Forth by men working a capstan that drove paddles on each side.

[15][16][17][18][19] In Europe from the 1820s, paddle steamers were used to take tourists from the rapidly expanding industrial cities on river cruises, or to the newly established seaside resorts, where pleasure piers were built to allow passengers to disembark regardless of the state of the tide.

Paddle steamer services continued into the mid-20th century, when ownership of motor cars finally made them obsolete except for a few heritage examples.

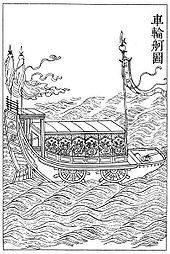

The ancient Chinese mathematician and astronomer Zu Chongzhi (429–500) had a paddle-wheel ship built on the Xinting River (south of Nanjing) known as the "thousand league boat".

A successful paddle-wheel warship design was made in China by Prince Li Gao in 784 AD, during an imperial examination of the provinces by the Tang dynasty (618–907) emperor.

In 1816 Pierre Andriel, a French businessman, bought in London the 15 hp (11 kW) paddle steamer Margery (later renamed Elise) and made an eventful London-Le Havre-Paris crossing, encountering heavy weather on the way.

One of the first screw-driven warships, HMS Rattler (1843), demonstrated her superiority over paddle steamers during numerous trials, including one in 1845 where she pulled a paddle-driven sister ship backwards in a tug of war.

[30] At the start of the First World War, the Royal Navy requisitioned more than fifty pleasure paddle steamers for use as auxiliary minesweepers.

[31] The large spaces on their decks intended for promenading passengers proved to be ideal for handling the minesweeping booms and cables, and the paddles allowed them to operate in coastal shallows and estuaries.

[32] In the Second World War, some thirty pleasure paddle steamers were again requisitioned;[31] an added advantage was that their wooden hulls did not activate the new magnetic mines.

More than twenty paddle steamers were used as emergency troop transports during the Dunkirk Evacuation in 1940,[31] where they were able to get close inshore to embark directly from the beach.

[33] One example was PS Medway Queen, which saved an estimated 7,000 men over the nine days of the evacuation, and claimed to have shot down three German aircraft.

[31] A number of paddle steamers participated in various roles in the Normandy landings in 1944 and supported the Allied advance along the coast of the Belgium and Holland.

Right: Detail of a steamer