Stoichiometry

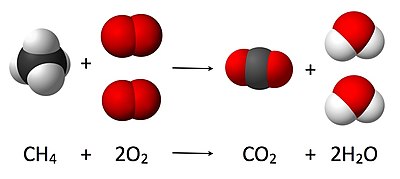

The numbers in front of each quantity are a set of stoichiometric coefficients which directly reflect the molar ratios between the products and reactants.

Stoichiometry measures these quantitative relationships, and is used to determine the amount of products and reactants that are produced or needed in a given reaction.

The term stoichiometry was first used by Jeremias Benjamin Richter in 1792 when the first volume of Richter's Anfangsgründe der Stöchyometrie oder Meßkunst chymischer Elemente (Fundamentals of Stoichiometry, or the Art of Measuring the Chemical Elements) was published.

[1] The term is derived from the Ancient Greek words στοιχεῖον stoikheîon "element"[2] and μέτρον métron "measure".

The number of molecules per mole in a substance is given by the Avogadro constant, exactly 6.02214076×1023 mol−1 since the 2019 revision of the SI.

For example, to find the amount of NaCl (sodium chloride) in 2.00 g, one would do the following: In the above example, when written out in fraction form, the units of grams form a multiplicative identity, which is equivalent to one (g/g = 1), with the resulting amount in moles (the unit that was needed), as shown in the following equation, Stoichiometry is often used to balance chemical equations (reaction stoichiometry).

For example, the two diatomic gases, hydrogen and oxygen, can combine to form a liquid, water, in an exothermic reaction, as described by the following equation: Reaction stoichiometry describes the 2:1:2 ratio of hydrogen, oxygen, and water molecules in the above equation.

For example, in the reaction the amount of water that will be produced by the combustion of 0.27 moles of CH3OH is obtained using the molar ratio between CH3OH and H2O of 2 to 4.

Now that the moles of Ag produced is known to be 0.5036 mol, we convert this amount to grams of Ag produced to come to the final answer: This set of calculations can be further condensed into a single step: For propane (C3H8) reacting with oxygen gas (O2), the balanced chemical equation is: The mass of water formed if 120 g of propane (C3H8) is burned in excess oxygen is then Stoichiometry is also used to find the right amount of one reactant to "completely" react with the other reactant in a chemical reaction – that is, the stoichiometric amounts that would result in no leftover reactants when the reaction takes place.

Percent yield, then, is expressed in the following equation: If 170.0 g of lead(II) oxide is obtained, then the percent yield would be calculated as follows: Consider the following reaction, in which iron(III) chloride reacts with hydrogen sulfide to produce iron(III) sulfide and hydrogen chloride: The stoichiometric masses for this reaction are: Suppose 90.0 g of FeCl3 reacts with 52.0 g of H2S.

The mass of HCl produced is 60.7 g. By looking at the stoichiometry of the reaction, one might have guessed FeCl3 being the limiting reactant; three times more FeCl3 is used compared to H2S (324 g vs 102 g).

In lay terms, the stoichiometric coefficient of any given component is the number of molecules and/or formula units that participate in the reaction as written.

In more technically precise terms, the stoichiometric number in a chemical reaction system of the i-th component is defined as or where

The convention is to assign negative numbers to reactants (which are consumed) and positive ones to products, consistent with the convention that increasing the extent of reaction will correspond to shifting the composition from reactants towards products.

Since any chemical component can participate in several reactions simultaneously, the stoichiometric number of the i-th component in the k-th reaction is defined as so that the total (differential) change in the amount of the i-th component is Extents of reaction provide the clearest and most explicit way of representing compositional change, although they are not yet widely used.

The accessible region of the hyperplane depends on the amounts of each chemical species actually present, a contingent fact.

As a consequence, extrema for the ξs will not occur unless an experimental system is prepared with zero initial amounts of some products.

Moles are most commonly used, but it is more suggestive to picture incremental chemical reactions in terms of molecules.

The Ns and ξs are reduced to molar units by dividing by the Avogadro constant.

Often the stoichiometry matrix is combined with the rate vector, v, and the species vector, x to form a compact equation, the biochemical systems equation, describing the rates of change of the molecular species: Gas stoichiometry is the quantitative relationship (ratio) between reactants and products in a chemical reaction with reactions that produce gases.

Often, but not always, the standard temperature and pressure (STP) are taken as 0 °C and 1 bar and used as the conditions for gas stoichiometric calculations.

Gas stoichiometry calculations solve for the unknown volume or mass of a gaseous product or reactant.

The ideal gas law can be re-arranged to obtain a relation between the density and the molar mass of an ideal gas: and thus: where: In the combustion reaction, oxygen reacts with the fuel, and the point where exactly all oxygen is consumed and all fuel burned is defined as the stoichiometric point.

Likewise, if the combustion is incomplete due to lack of sufficient oxygen, fuel remains unreacted.

Diesel engines, in contrast, run lean, with more air available than simple stoichiometry would require.