Strabo

[4] Strabo wrote that "great promises were made in exchange for these services", and as Persian culture endured in Amaseia even after Mithridates and Tigranes were defeated, scholars have speculated about how the family's support for Rome might have affected their position in the local community, and whether they might have been granted Roman citizenship as a reward.

He journeyed to Egypt and Kush, as far west as coastal Tuscany and as far south as Ethiopia in addition to his travels in Asia Minor and the time he spent in Rome.

Travel throughout the Mediterranean and Near East, especially for scholarly purposes, was popular during this era and was facilitated by the relative peace enjoyed throughout the reign of Augustus (27 BC – AD 14).

[5] The latest passage to which a date can be assigned is his reference to the death in AD 23 of Juba II, king of Maurousia (Mauretania), who is said to have died "just recently".

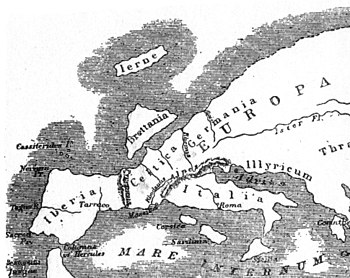

It is an encyclopaedic chronicle and consists of political, economic, social, cultural, and geographic descriptions covering almost all of Europe and the Mediterranean: Britain and Ireland, the Iberian Peninsula, Gaul, Germania, the Alps, Italy, Greece, Northern Black Sea region, Anatolia, Middle East, Central Asia and North Africa.

[8] The first of Strabo's major works, Historical Sketches (Historica hypomnemata), written while he was in Rome (c. 20 BC), is nearly completely lost.

The first chapter of his education took place in Nysa (modern Sultanhisar, Turkey) under the master of rhetoric Aristodemus, who had formerly taught the sons of the Roman general who had taken over Pontus.

[n 5] At around the age of 21, Strabo moved to Rome, where he studied philosophy with the Peripatetic Xenarchus, a highly respected tutor in Augustus's court.

The final noteworthy mentor to Strabo was Athenodorus Cananites, a philosopher who had spent his life since 44 BC in Rome forging relationships with the Roman elite.

He travelled extensively, as he says: "Westward I have journeyed to the parts of Etruria opposite Sardinia; towards the south from the Euxine [Black Sea] to the borders of Ethiopia; and perhaps not one of those who have written geographies has visited more places than I have between those limits.

[12] Alexandria itself features extensively in the last book of Geographica, which describes it as a thriving port city with a highly developed local economy.

But while he acknowledges and even praises Roman ascendancy in the political and military sphere, he also makes a significant effort to establish Greek primacy over Rome in other contexts."

In Europe, Strabo was the first to connect the Danube (which he called Danouios) and the Istros – with the change of names occurring at "the cataracts," the modern Iron Gates on the Romanian/Serbian border.

[citation needed] Charles Lyell, in his Principles of Geology, wrote of Strabo:[18] He notices, amongst others, the explanation of Xanthus the Lydian, who said that the seas had once been more extensive, and that they had afterwards been partially dried up, as in his own time many lakes, rivers, and wells in Asia had failed during a season of drought.

Strabo commented on fossil formation mentioning Nummulite (quoted from Celâl Şengör):[1]One extraordinary thing which I saw at the pyramids must not be omitted.

Some assume that these ashes were the result of thunderbolts and subterranean explosions, and do not doubt that the legendary story of Typhon takes place in this region.