Strategy of the Roman military

Such a reactive policy, whilst possibly more efficient than the maintenance of a standing army, does not indicate the close ties between long-term political goals and military organization demanded by grand strategy.

In the Empire, as the need for and size of the professional army grew, the possibility arose for the expansion of the concept of a grand strategy to encompass the management of the resources of the entire Roman state in the conduct of warfare: great consideration was given in the Empire to diplomacy and the use of the military to achieve political goals, both through warfare and also as a deterrent.

Vegetius once wrote that "every plan... is to be considered, every expedient tried and every method taken before matters are brought to this last extremity [general engagements]... Good officers decline general engagements where the odds are too great, and prefer the employment of stratagem and finesse to destroy the enemy as much as possible... without exposing their own forces.".

During this period, and for much of the Empire, it can be argued that the Romans did follow a grand strategy calling for limited direct operational engagement.

When a campaign did go badly wrong, operational strategy varied greatly as the circumstances dictated, from naval actions to sieges, assaults of fortified positions and open battle.

However, the preponderance of Roman campaigns exhibit a preference for direct engagement in open battle and, where necessary, the overcoming of fortified positions via military engineering.

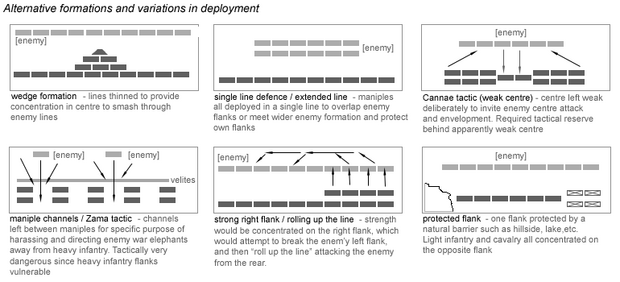

Roman armies of the Republic and early empire worked from a set tactical 'handbook', a military tradition of deploying forces that provided for few variations and was ignored or elaborated only on occasion.

At the end of a day's march, the Romans would typically establish a strong field camp called a castra, complete with palisade and a deep ditch, providing a basis for supply storage, troop marshalling and defence.

The soldiers were long-term service professionals whose interest lay in gaining a large pension and an allocation of land on retirement from the army, rather than in seeking glory on the battlefield as a warrior.

These war machines, a form of ancient artillery, launched arrows and large stones towards the enemy, proving most effective against close-order formations and structures.