Stratification (water)

Stratification is a barrier to the vertical mixing of water, which affects the exchange of heat, carbon, oxygen and nutrients.

Stratification occurs in several kinds of water bodies, such as oceans, lakes, estuaries, flooded caves, aquifers and some rivers.

The driving force in stratification is gravity, which sorts adjacent arbitrary volumes of water by local density, operating on them by buoyancy and weight.

Once a body of water has reached a stable state of stratification, and no external forces or energy are applied, it will slowly mix by diffusion until homogeneous in density, temperature and composition, varying only due to minor effects of compressibility.

Among these are heat input from the sun, which warms the upper volume, making it expand slightly and decreasing the density, so this tends to increase or stabilise stratification.

Mass movement of water between latitudes is affected by coriolis forces, which impart motion across the current direction, and movement towards or away from a land mass or other topographic obstruction may leave a deficit or excess which lowers or raises the sea level locally, driving upwelling and downwelling to compensate.

Downwelling also occurs in anti-cyclonic regions of the ocean where warm rings spin clockwise, causing surface convergence.

Stratified layers act as a barrier to the mixing of water, which impacts the exchange of heat, carbon, oxygen and other nutrients.

[1] This means that the differences in density of the layers in the oceans increase, leading to larger mixing barriers and other effects.

[1] Increasing stratification is predominantly affected by changes in ocean temperature; salinity only plays a role locally.

[1] An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea.

Vertical mixing determines how much the salinity and temperature will change from the top to the bottom, profoundly affecting water circulation.

Vertical mixing occurs at three levels: from the surface downward by wind forces, the bottom upward by turbulence generated at the interface between the estuarine and oceanic water masses, and internally by turbulent mixing caused by the water currents which are driven by the tides, wind, and river inflow.

River water dominates in this system, and tidal effects have a small role in the circulation patterns.

As a velocity difference develops between the two layers, shear forces generate internal waves at the interface, mixing the seawater upward with the freshwater.

[citation needed] As tidal forcing increases, the control of river flow on the pattern of circulation in the estuary becomes less dominating.

Turbulent eddies mix the water column, creating a mass transfer of freshwater and seawater in both directions across the density boundary.

If tidal currents at the mouth of an estuary are strong enough to create turbulent mixing, vertically homogeneous conditions often develop.

[10] Fjords are usually examples of highly stratified estuaries; they are basins with sills and have freshwater inflow that greatly exceeds evaporation.

A slow import of seawater may flow over the sill and sink to the bottom of the fjord (deep layer), where the water remains stagnant until flushed by an occasional storm.

In shallow lakes, stratification into epilimnion, metalimnion, and hypolimnion often does not occur, as wind or cooling causes regular mixing throughout the year.

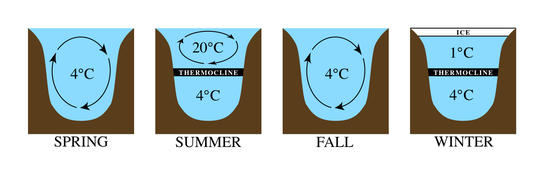

[19] Recent research suggests that seasonally ice-covered dimictic lakes may be described as "cryostratified" or "cryomictic" according to their wintertime stratification regimes.

[20] Karst caves which drain into the sea may have a halocline separating the fresh water from the seawater underneath which can be visible even when both layers are clear due to the difference in refractive indices.

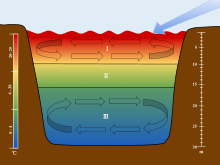

I. The Epilimnion

II. The Metalimnion

III. The Hypolimnion