Water resources

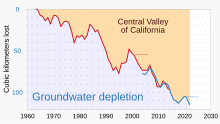

[2] The remaining unfrozen freshwater is found mainly as groundwater, with only a small fraction present above ground or in the air.

Humans often increase runoff quantities and velocities by paving areas and channelizing the stream flow.

Brazil is estimated to have the largest supply of fresh water in the world, followed by Russia and Canada.

[6] A unit of rock or an unconsolidated deposit is called an aquifer when it can yield a usable quantity of water.

Throughout the course of a river, the total volume of water transported downstream will often be a combination of the visible free water flow together with a substantial contribution flowing through rocks and sediments that underlie the river and its floodplain called the hyporheic zone.

Reuse may include irrigation of gardens and agricultural fields or replenishing surface water and groundwater.

Modern interest in desalination mostly focuses on cost-effective provision of fresh water for human use.

[24][23] A 2021 study proposed hypothetical portable solar-powered atmospheric water harvesting devices.

Irrigation helps to grow crops, maintain landscapes, and revegetate disturbed soils in dry areas and during times of below-average rainfall.

In addition to these uses, irrigation is also employed to protect crops from frost,[28] suppress weed growth in grain fields, and prevent soil consolidation.

Drainage, which involves the removal of surface and sub-surface water from a given location, is often studied in conjunction with irrigation.

Micro-irrigation is a system that distributes water under low pressure through a piped network and applies it as a small discharge to each plant.

It involves artificially raising the water table to moisten the soil below the root zone of plants.

Hydroelectric power derives energy from the force of water flowing downhill, driving a turbine connected to a generator.

Heat from the sun evaporates water, which condenses as rain in higher altitudes and flows downhill.

[29] These include drinking water, bathing, cooking, toilet flushing, cleaning, laundry and gardening.

With the growing uncertainties of global climate change and the long-term impacts of past management actions, this decision-making will be even more difficult.

As a result, alternative management strategies, including participatory approaches and adaptive capacity are increasingly being used to strengthen water decision-making.

As with other resource management, this is rarely possible in practice so decision-makers must prioritise issues of sustainability, equity and factor optimisation (in that order!)

[54] IWRM is a paradigm that emerged at international conferences in the late 1900s and early 2000s, although participatory water management institutions have existed for centuries.

This concept aims to promote changes in practices which are considered fundamental to improved water resource management.

IWRM was a topic of the second World Water Forum, which was attended by a more varied group of stakeholders than the preceding conferences and contributed to the creation of the GWP.

[58] The third World Water Forum recommended IWRM and discussed information sharing, stakeholder participation, and gender and class dynamics.

[55] Operationally, IWRM approaches involve applying knowledge from various disciplines as well as the insights from diverse stakeholders to devise and implement efficient, equitable and sustainable solutions to water and development problems.

As such, IWRM is a comprehensive, participatory planning and implementation tool for managing and developing water resources in a way that balances social and economic needs, and that ensures the protection of ecosystems for future generations.

Some of the cross-cutting conditions that are also important to consider when implementing IWRM are: Political will and commitment, capacity development, adequate investment, financial stability and sustainable cost recovery, monitoring and evaluation.

IWRM practices depend on context; at the operational level, the challenge is to translate the agreed principles into concrete action.

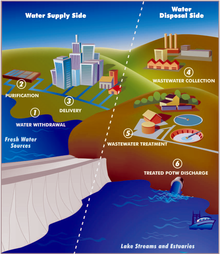

IUWM seeks to change the impact of urban development on the natural water cycle, based on the premise that by managing the urban water cycle as a whole; a more efficient use of resources can be achieved providing not only economic benefits but also improved social and environmental outcomes.

One approach is to establish an inner, urban, water cycle loop through the implementation of reuse strategies.

Accounting for flows in the pre- and post-development systems is an important step toward limiting urban impacts on the natural water cycle.