Stress (biology)

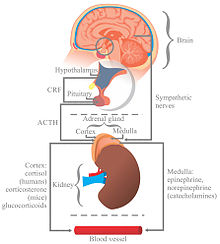

[4] The SAM and HPA axes are regulated by several brain regions, including the limbic system, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, hypothalamus, and stria terminalis.

[6] The International Classification of Diseases includes a group of mental and behavioral disorders which have their aetiology in reaction to severe stress and the consequent adaptive response.

[7][8] Chronic stress, and a lack of coping resources available, or used by an individual, can often lead to the development of psychological issues such as delusions,[9] depression and anxiety.

Studies have also shown that psychological stress may directly contribute to the disproportionately high rates of coronary heart disease morbidity and mortality and its etiologic risk factors.

[18] Physiological stress represents a wide range of physical responses that occur as a direct effect of a stressor causing an upset in the homeostasis of the body.

On the other hand, an organism's attempt at restoring conditions back to or near homeostasis, often consuming energy and natural resources, can also be interpreted as stress.

[30] Biology primarily attempts to explain major concepts of stress using a stimulus-response paradigm, broadly comparable to how a psychobiological sensory system operates.

The central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) plays a crucial role in the body's stress-related mechanisms.

The sympathetic nervous system becomes primarily active during a stress response, regulating many of the body's physiological functions in ways that ought to make an organism more adaptive to its environment.

The ANS directly innervates tissue through the postganglionic nerves, which is controlled by preganglionic neurons originating in the intermediolateral cell column.

The ANS receives inputs from the medulla, hypothalamus, limbic system, prefrontal cortex, midbrain and monoamine nuclei.

The fight or flight response to emergency or stress involves mydriasis, increased heart rate and force contraction, vasoconstriction, bronchodilation, glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, lipolysis, sweating, decreased motility of the digestive system, secretion of the epinephrine and cortisol from the adrenal medulla, and relaxation of the bladder wall.

[35] ANS related mechanisms are thought to contribute to increased risk of cardiovascular disease after major stressful events.

[37] The secretion of ACTH into systemic circulation allows it to bind to and activate Melanocortin receptor, where it stimulates the release of steroid hormones.

Steroid hormones bind to glucocorticoid receptors in the brain, providing negative feedback by reducing ACTH release.

Generally, the amygdala stimulates, and the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus attenuate, HPA axis activity; however, complex relationships do exist between the regions.

The sympathetic nervous system innervates various immunological structures, such as bone marrow and the spleen, allowing for it to regulate immune function.

[43][44] A 2024 review reported that the global estimated lifetime prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults is approximately 3.9%.

[4] Persistent stress that is not resolved through coping or adaptation, deemed distress, may lead to anxiety or withdrawal (depression) behavior.

He argued that cognitive processes of appraisal are central in determining whether a situation is potentially threatening, constitutes a harm/loss or a challenge, or is benign.

His theories of a universal non-specific stress response attracted great interest and contention in academic physiology and he undertook extensive research programs and publication efforts.

[61] While the work attracted continued support from advocates of psychosomatic medicine, many in experimental physiology concluded that his concepts were too vague and unmeasurable.

A broad biopsychosocial concept of stress and adaptation offered the promise of helping everyone achieve health and happiness by successfully responding to changing global challenges and the problems of modern civilization.

He argued that all people have a natural urge and need to work for their own benefit, a message that found favor with industrialists and governments.

By the late 1970s, stress had become the medical area of greatest concern to the general population, and more basic research was called for to better address the issue.

There was also renewed laboratory research into the neuroendocrine, molecular, and immunological bases of stress, conceived as a useful heuristic not necessarily tied to Selye's original hypotheses.

The US military became a key center of stress research, attempting to understand and reduce combat neurosis and psychiatric casualties.

[63] PTSD was considered a severe and ongoing emotional reaction to an extreme psychological trauma, and as such often associated with soldiers, police officers, and other emergency personnel.

By the 1990s, "stress" had become an integral part of modern scientific understanding in all areas of physiology and human functioning, and one of the great metaphors of Western life.

It came to cover a huge range of phenomena from mild irritation to the kind of severe problems that might result in a real breakdown of health.

hypothalamus =

amygdala =

hippocampus/ fornix =

pons=

pituitary gland=