Stress–strain analysis

In simple terms we can define stress as the force of resistance per unit area, offered by a body against deformation.

Stress analysis is a primary task for civil, mechanical and aerospace engineers involved in the design of structures of all sizes, such as tunnels, bridges and dams, aircraft and rocket bodies, mechanical parts, and even plastic cutlery and staples.

Typically, the starting point for stress analysis are a geometrical description of the structure, the properties of the materials used for its parts, how the parts are joined, and the maximum or typical forces that are expected to be applied to the structure.

The analysis may consider forces that vary with time, such as engine vibrations or the load of moving vehicles.

The term stress analysis is used throughout this article for the sake of brevity, but it should be understood that the strains, and deflections of structures are of equal importance and in fact, an analysis of a structure may begin with the calculation of deflections or strains and end with calculation of the stresses.

In stress analysis one normally disregards the physical causes of forces or the precise nature of the materials.

With very rare exceptions (such as ferromagnetic materials or planet-scale bodies), internal forces are due to very short range intermolecular interactions, and are therefore manifested as surface contact forces between adjacent particles — that is, as stress.

In principle, that means determining, implicitly or explicitly, the Cauchy stress tensor at every point.

[3] The external forces may be body forces (such as gravity or magnetic attraction), that act throughout the volume of a material;[4] or concentrated loads (such as friction between an axle and a bearing, or the weight of a train wheel on a rail), that are imagined to act over a two-dimensional area, or along a line, or at single point.

The same net external force will have a different effect on the local stress depending on whether it is concentrated or spread out.

In civil engineering applications, one typically considers structures to be in static equilibrium: that is, are either unchanging with time, or are changing slowly enough for viscous stresses to be unimportant (quasi-static).

In mechanical and aerospace engineering, however, stress analysis must often be performed on parts that are far from equilibrium, such as vibrating plates or rapidly spinning wheels and axles.

In structural design applications, one usually tries to ensure the stresses are everywhere well below the yield strength of the material.

The basic stress analysis problem can be formulated by Euler's equations of motion for continuous bodies (which are consequences of Newton's laws for conservation of linear momentum and angular momentum) and the Euler-Cauchy stress principle, together with the appropriate constitutive equations.

External forces that are specified as line loads (such as traction) or point loads (such as the weight of a person standing on a roof) introduce singularities in the stress field, and may be introduced by assuming that they are spread over small volume or surface area.

When the applied loads cause permanent deformation, one must use more complicated constitutive equations, that can account for the physical processes involved (plastic flow, fracture, phase change, etc.)

That is, the deformations caused by internal stresses are linearly related to the applied loads.

Such built-in stress may occur due to many physical causes, either during manufacture (in processes like extrusion, casting or cold working), or after the fact (for example because of uneven heating, or changes in moisture content or chemical composition).

Stress analysis is simplified when the physical dimensions and the distribution of loads allow the structure to be treated as one- or two-dimensional.

For orthotropic materials such as wood, whose stiffness is symmetric with respect to each of three orthogonal planes, nine coefficients suffice to express the stress–strain relationship.

In any case, for two- or three-dimensional domains one must solve a system of partial differential equations with specified boundary conditions.

Analytical (closed-form) solutions to the differential equations can be obtained when the geometry, constitutive relations, and boundary conditions are simple enough.

The design factor (a number greater than 1.0) represents the degree of uncertainty in the value of the loads, material strength, and consequences of failure.

The limit stress, for example, is chosen to be some fraction of the yield strength of the material from which the structure is made.

The purpose of maintaining a factor of safety on yield strength is to prevent detrimental deformations that would impair the use of the structure.

{\displaystyle {\text{maximum allowable stress}}={\frac {\text{ultimate tensile strength}}{\text{factor of safety}}}}

When a structural element is subjected to tension or compression its length will tend to elongate or shorten, and its cross-sectional area changes by an amount that depends on the Poisson's ratio of the material.

The surface of the ellipsoid represents the locus of the endpoints of all stress vectors acting on all planes passing through a given point in the continuum body.

However, numerical analysis and analytical methods allow only for the calculation of the stress tensor at a certain number of discrete material points.

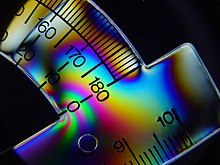

To graphically represent in two dimensions this partial picture of the stress field different sets of contour lines can be used:[6]