Structural coloration

For example, peacock tail feathers are pigmented brown, but their microscopic structure makes them also reflect blue, turquoise, and green light, and they are often iridescent.

The most brilliant blue coloration known in any living tissue is found in the marble berries of Pollia condensata, where a spiral structure of cellulose fibrils produces Bragg's law scattering of light.

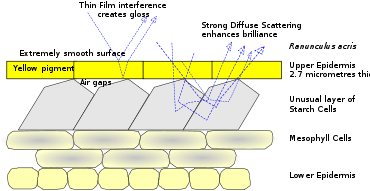

The bright gloss of buttercups is produced by thin-film reflection by the epidermis supplemented by yellow pigmentation, and strong diffuse scattering by a layer of starch cells immediately beneath.

Structural coloration has potential for industrial, commercial and military applications, with biomimetic surfaces that could provide brilliant colours, adaptive camouflage, efficient optical switches and low-reflectance glass.

[4][5] In his 1892 book Animal Coloration, Frank Evers Beddard (1858–1925) acknowledged the existence of structural colours: The colours of animals are due either solely to the presence of definite pigments in the skin, or … beneath the skin; or they are partly caused by optical effects due to the scattering, diffraction or unequal refraction of the light rays.

[9] Structural coloration is responsible for the blues and greens of the feathers of many birds (the bee-eater, kingfisher and roller, for example), as well as many butterfly wings, beetle wing-cases (elytra) and (while rare among flowers) the gloss of buttercup petals.

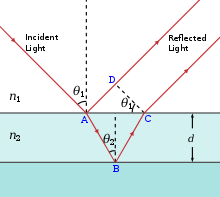

[11] Iridescence, as explained by Thomas Young in 1803, is created when extremely thin films reflect part of the light falling on them from their top surfaces.

A diffraction grating constructed of layers of chitin and air gives rise to the iridescent colours of various butterfly wing scales as well as to the tail feathers of birds such as the peacock.

Another way to produce a diffraction grating is with tree-shaped arrays of chitin, as in the wing scales of some of the brilliantly coloured tropical Morpho butterflies (see drawing).

[16] In Parides sesostris, the emerald-patched cattleheart butterfly,[17] photonic crystals are formed of arrays of nano-sized holes in the chitin of the wing scales.

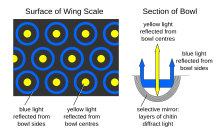

[19][20] Selective mirrors to create interference effects are formed of micron-sized bowl-shaped pits lined with multiple layers of chitin in the wing scales of Papilio palinurus, the emerald swallowtail butterfly.

[10] Crystal fibres, formed of hexagonal arrays of hollow nanofibres, create the bright iridescent colours of the bristles of Aphrodita, the sea mouse, a non-wormlike genus of marine annelids.

[22] Deformed matrices, consisting of randomly oriented nanochannels in a spongelike keratin matrix, create the diffuse non-iridescent blue colour of Ara ararauna, the blue-and-yellow macaw.

[10][23] Spiral coils, formed of helicoidally stacked cellulose microfibrils, create Bragg reflection in the "marble berries" of the African herb Pollia condensata, resulting in the most intense blue coloration known in nature.

[24] The berry's surface has four layers of cells with thick walls, containing spirals of transparent cellulose spaced so as to allow constructive interference with blue light.

Pollia produces a stronger colour than the wings of Morpho butterflies, and is one of the first instances of structural coloration known from any plant.

The curved petals form a paraboloidal dish which directs the sun's heat to the reproductive parts at the centre of the flower, keeping it some degrees Celsius above the ambient temperature.

[28] In this structural coloration mechanism, light rays that travel by different paths of total internal reflection along an interface interfere to generate iridescent colour.

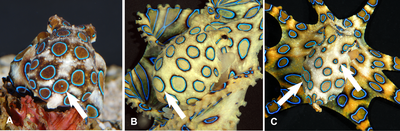

[10] Blue-ringed octopuses spend much of their time hiding in crevices whilst displaying effective camouflage patterns with their dermal chromatophore cells.

In 2010, the dressmaker Donna Sgro made a dress from Teijin Fibers' Morphotex, an undyed fabric woven from structurally coloured fibres, mimicking the microstructure of Morpho butterfly wing scales.

A direct parallel would be to create active or adaptive military camouflage fabrics that vary their colours and patterns to match their environments, just as chameleons and cephalopods do.

[10] The surface of the compound eye of the housefly is densely packed with microscopic projections that have the effect of reducing reflection and hence increasing transmission of incident light.

[38] Antireflective biomimetic surfaces using the "moth-eye" principle can be manufactured by first creating a mask by lithography with gold nanoparticles, and then performing reactive-ion etching.