Students for a Democratic Society

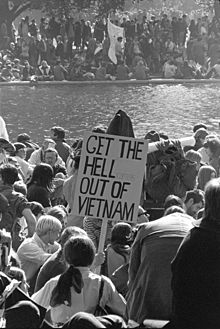

The organization splintered at that convention amidst rivalry between factions seeking to impose national leadership and direction, and disputing "revolutionary" positions on, among other issues, the Vietnam War and Black Power.

Progressive Era Repression and persecution Anti-war and civil rights movements Contemporary SDS developed from the youth branch of a socialist educational organization known as the League for Industrial Democracy (LID).

LID itself descended from an older student organization, the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, founded in 1905 by Upton Sinclair, Walter Lippmann, Clarence Darrow, and Jack London.

The SDS manifesto, known as the Port Huron Statement, was adopted at the organization's first convention in June 1962,[2] based on an earlier draft by staff member Tom Hayden.

[3] The Port Huron Statement decried what it described as "disturbing paradoxes": that the world's "wealthiest and strongest country" should "tolerate anarchy as a major principle of international conduct"; that it should allow "the declaration 'all men are created equal...'" to ring "hollow before the facts of Negro life"; that, even as technology creates "new forms of social organization", it should continue to impose "meaningless work and idleness"; and with two-thirds of mankind undernourished that its "upper classes" should "revel amidst superfluous abundance".

The Statement omitted the LID's standard denunciation of communism: the regret it expressed at the "perversion of the older left by Stalinism" was too discriminating, and its references to Cold War tensions too even handed.

From November 1963 through April 1964, the demonstrations focused on ending the de facto segregation that resulted in the racial categorization of Chester public schools, even after the landmark Supreme Court case Brown v. The Board of Education of Topeka.

[12][13] Conceived in part as a response to the gathering danger of a "white backlash", and with $5,000 from United Automobile Workers union, Tom Hayden promoted an Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP).

[16] Ralph Helstein, president of the United Packinghouse Workers of America, arranged for Hayden and Gitlin to meet with Saul Alinsky who, with 25 years experience in Chicago and across the country, was the acknowledged father of community organizing.

Placing a premium on strong local leadership, structure and accountability, Alinsky's "citizen participation" was something "fundamentally different" from the "participatory democracy" envisaged by Hayden and Gitlin.

The "whole balance of the organization shifted to ERAP headquarters in Ann Arbor",[18] the new national secretary, C. Clark Kissinger cautioned against "the temptation to 'take one generation of campus leadership and run!'

[22][23] However much the volunteers might talk at night about "transforming the system", "building alternative institutions," and "revolutionary potential", credibility on the doorstep rested on their ability to secure concessions from, and thus to develop relations with, the local power structures.

[24] Lyndon B. Johnson's landslide in the November 1964 presidential election swamped considerations of Democratic-primary, or independent candidature, interventions—a path that had been tentatively explored in a Political Education Project.

Local chapters expanded activity across a range of projects, including University reform, community-university relations, and were beginning to focus on the issue of the draft and Vietnam War.

The National Convention in Akron (which FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover reported was attended by "practically every subversive organization in the United States")[27] selected as President Carl Oglesby (Antioch College).

Jane Adams, former Mississippi Freedom Summer volunteer and SDS campus traveler in Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, and Missouri, was elected Interim National Secretary.

Students are going to make the revolution because we have the will.After a three-hour open mike meeting in the Life Sciences building, instead of closing with the civil-rights anthem "We Shall Overcome", the crowd "grabbed hands and sang the chorus to 'Yellow Submarine'".

"[39] Inspired by a leaflet distributed by some poets in San Francisco, and organized by the Rag and the SDS in the belief that "there is nothing wrong with fun", a "Gentle Thursday" event in the fall of 1966 drew hundreds of area residents, bringing kids, dogs, balloons, picnics and music, to the UT West Mall.

It included appearances by Stokley Carmichael, beat-poet Allen Ginsberg, and anti-war protests at the Texas State Capitol during a visit by Vice-President Hubert Humphrey.

After conventional civil rights tactics of peaceful pickets seemed to have failed, the Oakland, California, Stop the Draft Week ended in mass hit and run skirmishes with the police.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), mainly through its secret COINTELPRO (COunter INTELligence PROgram) and other law enforcement agencies were often exposed as having spies and informers in the chapters.

In the spring of 1968, National SDS activists led an effort on the campuses called "Ten Days of Resistance" and local chapters cooperated with the Student Mobilization Committee in rallies, marches, sit-ins and teach-ins, and on April 18 in a one-day strike.

Although herself regarded as "one of the boys", her recollection of those early SDS meetings is of interminable debate driven by young male intellectual posturing and, if a woman commented, of being made to feel as if a child had spoken among adults.

[47] Seeking the "roots of the women's liberation movement" in the New Left, Sara Evans argues that in Hayden's ERAP program this presumption of male agency had been one of the undeclared sources of tension.

While open in acknowledging the debt they believed they owed to SNCC and to the Black Panthers, many were conscious that their poor white, and in some cases southern, backgrounds had limited their acceptance in "the Movement".

But at the first national council meeting after the convention (University of Colorado, Boulder, October 11–13), the Worker Student Alliance had their line confirmed: attempts to influence political parties in the United States fostered an "illusion" that people can have democratic power over system institutions.

The PLP condemned the protest in Chicago not only because there had been the "illusion" that the system could be effectively pressured or lobbied, but because, in their view, the "wild-in-the-streets" resistance estranged "the working masses" and made it more difficult for the left to build a popular base.

[66] At a time when the New Left Notes could describe the SDS as "a confederation of localized conglomerations of people held together by one name",[67] and as events in the country continued to drift, what the PLP-WSA offered was the promise of organizational discipline and of a consistent vision.

To students "just beginning to be aware of their own radicalization and their potential role as the intelligentsia in an American left", the SDS was proposing that the "only really important agents for social change were the industrial workers, or the ghetto blacks, or the Third World revolutionaries."

In alliance with "the Black Liberation Movement", a "white fighting force" would "bring the war home"[73] On October 6, 1969, the Weathermen planted their first bomb, blowing up a statue in Chicago commemorating police officers killed during the 1886 Haymarket Riot.