Kingdom (biology)

The terms flora (for plants), fauna (for animals), and, in the 21st century, funga (for fungi) are also used for life present in a particular region or time.

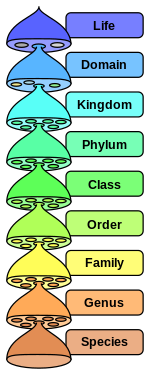

[3] Later two further main ranks were introduced, making the sequence kingdom, phylum or division, class, order, family, genus and species.

[5] Prefixes can be added so subkingdom (subregnum) and infrakingdom (also known as infraregnum) are the two ranks immediately below kingdom.

Linnaeus also included minerals in his classification system, placing them in a third kingdom, Regnum Lapideum.

In 1674, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, often called the "father of microscopy", sent the Royal Society of London a copy of his first observations of microscopic single-celled organisms.

However, by the mid–19th century, it had become clear to many that "the existing dichotomy of the plant and animal kingdoms [had become] rapidly blurred at its boundaries and outmoded".

[8] Haeckel revised the content of this kingdom a number of times before settling on a division based on whether organisms were unicellular (Protista) or multicellular (animals and plants).

[8][9] In the 1960s, Roger Stanier and C. B. van Niel promoted and popularized Édouard Chatton's earlier work, particularly in their paper of 1962, "The Concept of a Bacterium"; this created, for the first time, a rank above kingdom—a superkingdom or empire—with the two-empire system of prokaryotes and eukaryotes.

The remaining two kingdoms, Protista and Monera, included unicellular and simple cellular colonies.

[12] Following publication of Whittaker's system, the five-kingdom model began to be commonly used in high school biology textbooks.

[16] This six-kingdom model is commonly used in recent US high school biology textbooks, but has received criticism for compromising the current scientific consensus.

Technological advances in electron microscopy allowed the separation of the Chromista from the Plantae kingdom.

Moreover, only chromists contain chlorophyll c. Since then, many non-photosynthetic phyla of protists, thought to have secondarily lost their chloroplasts, were integrated into the kingdom Chromista.

[18] As mitochondria were known to be the result of the endosymbiosis of a proteobacterium, it was thought that these amitochondriate eukaryotes were primitively so, marking an important step in eukaryogenesis.

[20][a][21] Cavalier-Smith no longer accepted the importance of the fundamental Eubacteria–Archaebacteria divide put forward by Woese and others and supported by recent research.

In the same way, his paraphyletic kingdom Protozoa includes the ancestors of Animalia, Fungi, Plantae, and Chromista.

The advances of phylogenetic studies allowed Cavalier-Smith to realize that all the phyla thought to be archezoans (i.e. primitively amitochondriate eukaryotes) had in fact secondarily lost their mitochondria, typically by transforming them into new organelles: Hydrogenosomes.

In 2004, a review article by Simpson and Roger noted that the Protista were "a grab-bag for all eukaryotes that are not animals, plants or fungi".

[42] On this basis, the diagram opposite (redrawn from their article) showed the real "kingdoms" (their quotation marks) of the eukaryotes.

), Haptophyta, Cryptophyta (or cryptomonads), and Alveolata Land plants, green algae, red algae, and glaucophytes In this system the multicellular animals (Metazoa) are descended from the same ancestor as both the unicellular choanoflagellates and the fungi which form the Opisthokonta.

The arguments against include the fact that they are obligate intracellular parasites that lack metabolism and are not capable of replication outside of a host cell.

[60][61] Another argument is that their placement in the tree would be problematic, since it is suspected that viruses have various evolutionary origins,[60] and they have a penchant for harvesting nucleotide sequences from their hosts.

[62] One of these comes from the discovery of unusually large and complex viruses, such as Mimivirus, that possess typical cellular genes.