Kingdom of the Suebi

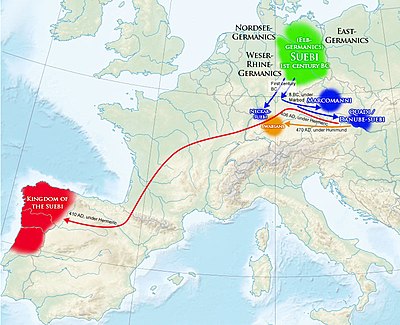

It is speculated that these Suevi are the same group as the Quadi, who are mentioned in early writings as living north of the middle Danube, in what is now lower Austria and western Slovakia,[3][4] and who played an important part in the Germanic Wars of the 2nd century, when, allied with the Marcomanni, they fought fiercely against the Romans under Marcus Aurelius.

Additionally it has been pointed out that the lack of mention of the Suevi could mean that they were not per se an older distinct ethnic group, but the result of a recent ethnogenesis, with many smaller groups—among them part of the Quadi and Marcomanni—coming together during the migration from the Danube valley to the Iberian Peninsula.

Gerontius responded by stirring up the barbarians in Gaul against Constantine, convincing them to mobilize again, and, in the summer of 409, the Vandals, Alans, and Suevi began pushing south towards Hispania.

[17] Hydatius writes that upon entering Hispania, the barbarian peoples, and even the Roman soldiers, spent 409–410 in a frenzy, plundering food and goods from the cities and countryside, which caused a famine that, according to Hydatius, forced the locals to resort to cannibalism: "[driven] by hunger human beings devoured human flesh; mothers too feasted upon the bodies of their own children whom they had killed and cooked with their own hands.

Many scholars believe that the reference to "lot" may be to the sortes, "allotments," which barbarian federates received from the Roman government, which suggests that the Suevi and the other invaders had signed a treaty with Maximus.

Soon Braga would become their capital, and their domain later expanded into Astorga, and in the region of Lugo and in the valley of the Minho river,[23] with no evidence suggesting that the Suevi inhabited any other cities in the province prior to 438.

In 438 Hermeric became ill. Having annexed the entirety of the former Roman province of Gallaecia, he made peace with the local population,[25] and retired, leaving his son Rechila as king of the Sueves.

In the same year he campaigned in Baetica, defeating in open battle the Romanae militiae dux Andevotus by the banks of the Genil river, capturing a large treasure.

Rechila continued with the expansion of the kingdom, and by 440 he fruitfully besieged and forced the surrender of a Roman official, count Censorius, in the strategic city of Mértola.

In 446, the Romans dispatched to the provinces of Baetica and Carthaginensis the magister utriusque militiae Vitus, who, assisted by a large number of Goths, attempted to subdue the Suevi and restore imperial administration in Hispania.

Theodoric continued his war on the Suevi for three months, but in April 459 he returned to Gaul, alarmed by the political and military movements of the new emperor, Majorian, and of the magister militum Ricimer—a half-Sueve, maybe a kinsman of Rechiar[43]—while his allies and the rest of the Goths sacked Astorga, Palencia and other places, on their way back to the Pyrenees.

In 460 Maldras was killed, after a reign of four years during which he plundered Sueves and Romans alike, in Lusitania and in the south of Gallaecia past the valley of the Douro river.

As a response, the Goths sent their army to punish the Suevi who dwelt in the outskirts of the city and nearby regions, but their campaign was revealed by some locals, whom Hydatius considered traitors.

In the south Frumar succeeded Maldras and his faction, but his death in 464 closed a period of internal dissent among the Sueves, and permanent conflict with the native Gallaecian population.

[65] Most of what is known about the settlement comes from ecclesiastical sources; records from the 572 Second Council of Braga refer to a diocese called the Britonensis ecclesia ("British church") and an episcopal see called the sedes Britonarum ("See of the Britons"), while the administrative and ecclesiastical document usually known as Divisio Theodemiri or Parochiale suevorum, attribute to them their own churches and the monastery Maximi, likely the monastery of Santa Maria de Bretoña.

The first Orthodox Council held in the Kingdom, it was almost entirely devoted to the condemnation of Priscillianism, making no mention at all of Arianism, and only once reproving clerics for adorning his clothes and for wearing granos, a Germanic word implying either pigtails, long beard, moustache, or a Suebian knot, a custom declared pagan.

Martin was a cultivated man, praised by Isidore of Seville, Venantius Fortunatus and Gregory of Tours, who led the Sueves to Catholicism and who promoted the cultural and political renaissance of the kingdom.

Notably, of the twelve assistant bishops, five were Sueves (Nitigius of Lugo, Wittimer of Ourense, Anila of Tui, Remisol of Viseu, Adoric of Idanha-a-Velha), and one was a Briton, Mailoc.

Under siege, Hermenegild's rebellion became dependent on the support offered by the Eastern Roman Empire, which controlled much of the southern coastal regions of Hispania since Justinian I, and by the Sueves.

After exchanging presents, Miro returned to Gallaecia, where he was laid to bed some days later, dying soon after, due to "the bad waters of Spain", according to Gregory of Tours.

In the words of John of Biclaro:[82] "King Liuvigild devastates Gallaecia and deprives Audeca of the totality of the Kingdom; the nation of the Sueves, their treasure and fatherland are conduced to his own power and turned into a province of the Goths."

During the campaign, the Franks of king Guntram attacked Septimania, maybe trying to help the Sueves,[83] at the same time sending ships to Gallaecia which were intercepted by Liuvigild's troops, who took their cargo and killed or enslaved most of their crews.

This same year, 585, a man named Malaric rebelled against the Goths and reclaimed the throne, but he was finally defeated and captured by the generals of Liuvigild, who took him in chains to the Visigothic king.

[89] The last mention of the Sueves as a separate people dates to a 10th-century gloss in a Spanish codex:[90] "hanc arbor romani pruni vocant, spani nixum, uuandali et goti et suebi et celtiberi ceruleum dicunt" ("This tree is called plum-tree by the Romans; nixum by the Spaniards; the Vandals, the Sueves, the Goths, and the Celtiberians call it ceruleum"), but in this context Suebi probably meant simply Gallaeci.

Again, they become important players during the reign of Miro, in the last third of the 6th century, when they allied with other Catholic powers—the Franks and the Eastern Romans—in support of Hermenegild, and against the Visigothic king Liuvigild.

Through much of his life he was forced to stay in isolated Roman communities, constantly threatened by the Suevi and Vandals,[93] though we also know that he travelled on several occasions outside of Hispania, for learning or as ambassador, and that he maintained correspondence with other bishops.

In his narration, Sueves and Vandals, after a violent entrance into Hispania, resume a pacific life, while many poor locals joined them, fleeing from Roman taxes and impositions.

[7] For the mid-fifth century we have also chapter 44 of Jordanes' Getica, which narrates the defeat of the Suevi king Rechiar at the hands of the Roman foederati troops commanded by the Visigoths.

The ending of the Chronicle of Hydatius, in 469, marks the beginning of a period of obscurity in the history of the Sueves, who don't re-emerge into historical light until the mid-sixth century, when we have plenty of sources.

Distinguishing between loanwords from Gothic or Suevic is difficult, but there is a series of words, characteristic of Galicia and northern half of Portugal, which are attributed either to the Suebi[105][106] or to the Goths, although no major Visigothic immigration into Gallaecia is known before the 8th century.