Necessity and sufficiency

In logic and mathematics, necessity and sufficiency are terms used to describe a conditional or implicational relationship between two statements.

[4][5][6] In ordinary English (also natural language) "necessary" and "sufficient" indicate relations between conditions or states of affairs, not statements.

In data analytics, necessity and sufficiency can refer to different causal logics,[7] where necessary condition analysis and qualitative comparative analysis can be used as analytical techniques for examining necessity and sufficiency of conditions for a particular outcome of interest.

Similarly, in order for human beings to live, it is necessary that they have air.

[9] One can also say S is a sufficient condition for N (refer again to the third column of the truth table immediately below).

If P is sufficient for Q, then knowing P to be true is adequate grounds to conclude that Q is true; however, knowing P to be false does not meet a minimal need to conclude that Q is false.

Similarly, a necessary and sufficient condition for invertibility of a matrix M is that M has a nonzero determinant.

Another facet of this duality is that, as illustrated above, conjunctions (using "and") of necessary conditions may achieve sufficiency, while disjunctions (using "or") of sufficient conditions may achieve necessity.

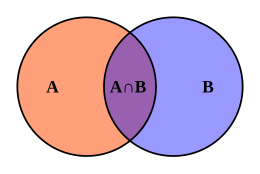

For a third facet, identify every mathematical predicate N with the set T(N) of objects, events, or statements for which N holds true; then asserting the necessity of N for S is equivalent to claiming that T(N) is a superset of T(S), while asserting the sufficiency of S for N is equivalent to claiming that T(S) is a subset of T(N).

Psychologically speaking, necessity and sufficiency are both key aspects of the classical view of concepts.

Under the classical theory of concepts, how human minds represent a category X, gives rise to a set of individually necessary conditions that define X.

[10] This contrasts with the probabilistic theory of concepts which states that no defining feature is necessary or sufficient, rather that categories resemble a family tree structure.

To say that P is necessary and sufficient for Q is to say two things: One may summarize any, and thus all, of these cases by the statement "P if and only if Q", which is denoted by

For example, in graph theory a graph G is called bipartite if it is possible to assign to each of its vertices the color black or white in such a way that every edge of G has one endpoint of each color.

And for any graph to be bipartite, it is a necessary and sufficient condition that it contain no odd-length cycles.

Thus, discovering whether a graph has any odd cycles tells one whether it is bipartite and conversely.

A philosopher[11] might characterize this state of affairs thus: "Although the concepts of bipartiteness and absence of odd cycles differ in intension, they have identical extension.

Because, as explained in previous section, necessity of one for the other is equivalent to sufficiency of the other for the first one, e.g.