Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik

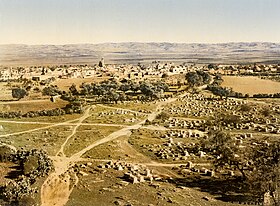

Lydda was at least partly destroyed and its inhabitants may have been forcibly relocated to Ramla, which developed into an economic hub, became home to many Muslim scholars, and remained the commercial and administrative center of Palestine until the 11th century.

Although he continued his predecessors' militarist policies, expansion largely stopped under Sulayman, partly due to effective resistance along the Central Asian frontiers and the collapse of Arab military leadership and organization there after Qutayba's death.

Sulayman's appointee over the eastern Caliphate, his confidant Yazid, invaded the southern Caspian coast in 716, but withdrew and settled for a tributary arrangement after being defeated by the local Iranian rulers.

The siege of Constantinople and the coinciding of his reign with the approaching centennial of the Hijra (start of the Islamic calendar), led contemporary Arab poets to view Sulayman in messianic terms.

[17] He established a strong relationship with Raja ibn Haywa al-Kindi, a local, Yamani-affiliated religious scholar who had previously supervised the construction of Abd al-Malik's Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.

[17] Sulayman resented the influence of al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, the viceroy of Iraq and the eastern parts of the Caliphate, over al-Walid,[18] and cultivated ties with his opponents.

[22] Hisham further noted "Yazid ... stayed with him [Sulayman], teaching him how to dress well, making delicious dishes for him, and giving him large presents".

[26] According to the historian Nimrod Luz, this was likely due to a lack of available space for wide-scale development and agreements dating to the Muslim conquest in the 630s that, at least formally, precluded him from confiscating desirable property within the city.

[29] In a tradition recorded by the historian Ibn Fadlallah al-Umari (d. 1347), a determined local Christian cleric refused Sulayman's requests for plots in the middle of Lydda.

[30] The historian Moshe Sharon holds that Lydda was "too Christian in ethos for the taste of the Umayyad rulers", particularly following the Arabization and Islamization reforms instituted by Abd al-Malik.

[32] In choosing the site, Sulayman utilized the strategic advantages of Lydda's vicinity while avoiding the physical constraints of an already-established urban center.

[36] From early on, Ramla developed economically as a market town for the surrounding area's agricultural products, and as a center for dyeing, weaving and pottery.

[37] Sulayman built an aqueduct in the city called al-Barada, which transported water to Ramla from Tel Gezer, about 10 kilometers (6 mi) to the southeast.

[43] According to an 8th-century Arabic source,[44] Sulayman ordered the construction of several public buildings there, including a bathhouse, at the same time that al-Walid was developing the Temple Mount (Haram al-Sharif).

[1][52] It is unclear whether these changes were the result of resentment and suspicion toward previous opponents of his accession, a means to ensure control over the provinces by appointing loyal officials, or a policy to end the rule of strong, old-established governors.

[54] Wellhausen held that Sulayman, from the time he was governor of Palestine, "may have been persuaded" that the rule of al-Hajjaj engendered hatred among the Iraqis toward the Umayyads rather than fostering their loyalty.

[56] A protege of al-Hajjaj, Qutayba ibn Muslim, whose relations with Sulayman had been antagonistic, was confirmed in his post by the Caliph, but remained wary that his dismissal was pending.

[58] Meanwhile, al-Hajjaj's kinsman and leader of the conquest of Sind, Muhammad ibn al-Qasim, did not revolt against Sulayman, but was nonetheless dismissed, summoned to Wasit, and tortured to death.

[1] The Caliph directed Yazid to relocate to Khurasan and leave lieutenant governors in the Iraqi garrison towns of Kufa, Basra and Wasit, while entrusting Iraq's fiscal affairs to his own appointee, a mawla (pl.

The assassination order was carried out by some of the leading Arab commanders in al-Andalus, including Abd al-Aziz's top lieutenant Habib ibn Abi Ubayd al-Fihri.

[1] On the eastern front, in Transoxiana, further conquests were not achieved for a quarter century after Qutayba's death, during which time the Arabs began to lose territory in the region.

[69][70] Yazid defeated the Chöl Turks north of the river Atrek, and secured control of Jurjan by founding a city there (modern Gonbad-e Kavus).

[72] Yazid's initial success was reversed by Tabaristan's ruler, Farrukhan the Great, and his coalition from neighboring Daylam, Gilan, and Jurjan in later confrontations that year.

[80][81] Aided by a prolonged period of instability in Byzantium,[80][82] by 712, the Byzantine defensive system began to show signs of collapse, as Arab raids penetrated ever deeper into Asia Minor.

[1] Being too ill to lead the campaign in person,[86] he dispatched his half-brother Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik to besiege the Byzantine capital from the land, with orders to remain until the city was conquered or he was recalled by the Caliph.

Nevertheless, the goal of conquering Constantinople was effectively abandoned, and the frontier between the two empires stabilized along the line of the Taurus and Anti-Taurus Mountains, over which both sides continued to launch regular raids and counter-raids during the next centuries.

[98] Raja counseled Sulayman to choose his paternal cousin and adviser, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, describing him as a "worthy, excellent man and a sincere Muslim".

[98] Sulayman's nomination of Umar over his own brothers defied the general assumptions among the Umayyad family that the office of the caliph would be restricted to the household of Abd al-Malik.

[106] Several Islamic traditional sources credited Sulayman for reversing al-Hajjaj's measures against non-Arab, Muslim converts by allowing the return to Basra of either the urban mawali who had supported the anti-Umayyad revolt of Ibn al-Ash'ath in 700–701, or the Iraqi peasants who converted to Islam and moved to Basra to avoid the jizya (poll tax designated for non-Muslims).

[113] In contrast to contemporary poetry, the Islamic tradition considers Sulayman to have been cruel and unjust, his overtures to the pious stemming from the guilt of his immoral conduct.

) in the year seven and ninety"

.

) in the year seven and ninety"

.