Sumerian language

It is a local language isolate that was spoken solely in ancient Mesopotamia, a region that is modern-day Iraq and parts of Southeast Turkey and Northeast Syria.

It corresponds mostly to the last part of the Early Dynastic period (ED IIIb) and specifically to the First Dynasty of Lagash, from where the overwhelming majority of surviving texts come.

There is a wealth of texts greater than from any preceding time – besides the extremely detailed and meticulous administrative records, there are numerous royal inscriptions, legal documents, letters and incantations.

[18] In spite of the dominant position of written Sumerian during the Ur III dynasty, it is controversial to what extent it was actually spoken or had already gone extinct in most parts of its empire.

[5][20] Nonetheless, it seems clear that by far the majority of scribes writing in Sumerian in this point were not native speakers and errors resulting from their Akkadian mother tongue become apparent.

[20][24] The Old Babylonian period, especially its early part,[10] has produced extremely numerous and varied Sumerian literary texts: myths, epics, hymns, prayers, wisdom literature and letters.

[51] Attempts have been made without success to link Sumerian with a range of widely disparate groups such as Indo-European, Austroasiatic,[52] Dravidian ,[53] Uralic,[54][55][56][57] Sino-Tibetan,[58] and Turkic (the last being promoted by Turkish nationalists as part of the Sun language theory[59][60]).

Over the long period of bi-lingual overlap of active Sumerian and Akkadian usage the two languages influenced each other, as reflected in numerous loanwords and even word order changes.

[69] Depending on the context, a cuneiform sign can be read either as one of several possible logograms, each of which corresponds to a word in the Sumerian spoken language, as a phonetic syllable (V, VC, CV, or CVC), or as a determinative (a marker of semantic category, such as occupation or place).

Credit for being first to scientifically treat a bilingual Sumerian-Akkadian text belongs to Paul Haupt, who published Die sumerischen Familiengesetze (The Sumerian family laws) in 1879.

[78] Friedrich Delitzsch published a learned Sumerian dictionary and grammar in the form of his Sumerisches Glossar and Grundzüge der sumerischen Grammatik, both appearing in 1914.

Piotr Michalowski's essay (entitled, simply, "Sumerian") in the 2004 The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages has also been recognized as a good modern grammatical sketch.

The consonants in parentheses are reconstructed by some scholars based on indirect evidence; if they existed, they were lost around the Ur III period in the late 3rd millennium BC.

[118] In earlier scholarship, somewhat different views were expressed and attempts were made to formulate detailed rules for the effect of grammatical morphemes and compounding on stress, but with inconclusive results.

[131] Consistent syllabic spelling was employed when writing down the Emesal dialect (since the usual logograms would have been read in Emegir by default), for the purpose of teaching the language and often in recording incantations.

A further oft-mentioned and paradoxical problem for the study of Sumerian is that the most numerous and varied texts written in the most phonetically explicit and precise orthography are only dated to periods when the scribes themselves were no longer native speakers and often demonstrably had less-than-perfect command of the language they were writing in; conversely, for much of the time during which Sumerian was still a living language, the surviving sources are few, unvaried and/or written in an orthography that is more difficult to interpret.

Finally, there is a third construction in which the possessive pronoun 𒁉 -bi is added after the numeral, which gives the whole phrase a definite meaning: 𒌉𒐈𒀀𒁉 dumu eš5-a-bi: "the three children" (lit.

[249][250] The Sumerian verb also makes a binary distinction according to a category that some regard as tense (past vs present-future), others as aspect (perfective vs imperfective), and that will be designated as TA (tense/aspect) in the following.

[286] Proposed explanations of the choice of conjugation prefix usually revolve around the subtleties of spatial grammar, information structure (focus[287]), verb valency, and, most recently, voice.

The use of the personal affixes for subjects and direct objects can be summarized as follows:[392] animate Examples for TA and pronominal agreement: (ḫamṭu is rendered with past tense, marû with present): The verbal stem itself can also express grammatical distinctions within the categories number and tense-aspect.

Unlike the enclitic, it typically uses the normal stem 𒈨 -me- in the 3rd person singular (𒁀𒊏𒈨 ba-ra-me "should not be"), except for the form prefixed with ḫa-, which is 𒃶𒅎 ḫe2-em or 𒃶𒀀𒀭 ḫe2-am3.

[464][465][466] According to them, too, a passive is formed by removing the ergative participant and the verbal marker that agrees with it, but the verb is not inflected as an intransitive one: instead, it has a personal prefix, which refers to the "logical object": {e i-b-řu} or {e ba-b-řu} "the house is being built".

[467] Critics have argued that most alleged examples of the construction are actually instances of the pre-stem personal prefix referring to the directive participant in an intransitive verb, at least before the Old Babylonian period.

The dependent may be: An older obsolete pattern was right-headed instead: A participle may be the head of the compound, preceded by a dependent: There are a few cases of nominalized finite verbs, too: 𒁀𒍗 ba-uš4 "(who) has died" > "dead" Abstract nouns are formed as compounds headed by the word 𒉆 nam- "fate, status": 𒌉 dumu "child" > 𒉆𒌉 nam-dumu "childhood", 𒋻 tar "cut, decide" > 𒉆𒋻 nam-tar "fate".

Alternatively, it has been contended that it must have been originally a regional dialect, since instances of apparent Emesal-like forms are attested in the area of late 3rd millennium Lagash,[534] and some loanwords into Akkadian appear to come from Emesal rather than Emegir.

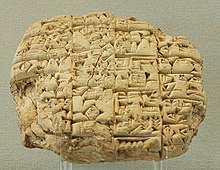

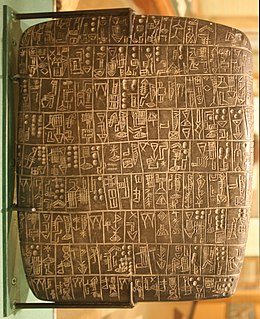

As used for the Sumerian language, the cuneiform script was in principle capable of distinguishing at least 16 consonants,[553][554] transliterated as as well as four vowel qualities, a, e, i, u. á 𒀉 é 𒂍 í=IÁ 𒐊, ì=NI 𒉌 ú 𒌑, ù 𒅇 á 𒀉 é 𒂍 í=IÁ 𒐊, ì=NI 𒉌 ú 𒌑, ù 𒅇 bá=PA 𒉺, bà=EŠ 𒌍 bé=BI 𒁉, bè=NI 𒉌 bí=NE 𒉈, bì=PI 𒉿 bú=KASKAL 𒆜, bù=PÙ 𒅤 áb 𒀖 éb=TUM 𒌈 íb=TUM 𒌈 úb=ŠÈ 𒂠 dá=TA 𒋫 dé 𒌣, dè=NE 𒉈 dí=TÍ 𒄭 dú=TU 𒌅, dù=GAG 𒆕, du4=TUM 𒌈 ád 𒄉 íd=A.ENGUR 𒀀𒇉 úd=ÁŠ 𒀾 gá 𒂷 gé=KID 𒆤, gè=DIŠ 𒁹 gí=KID 𒆤, gì=DIŠ 𒁹, gi4 𒄄, gi5=KI 𒆠 gú 𒄘, gù=KA 𒅗, gu4 𒄞, gu5=KU 𒆪, gu6=NAG 𒅘, gu7 𒅥 ág 𒉘 ég=E 𒂊 íg=E 𒂊 ḫá=ḪI.A 𒄭𒀀, ḫà=U 𒌋, ḫa4=ḪI 𒄭 ḫé=GAN 𒃶 ḫí=GAN 𒃶 áḫ=ŠEŠ 𒋀 úḫ 𒌔 ká 𒆍, kà=GA 𒂵 ké=GI 𒄀 kí=GI 𒄀 kú=GU7 𒅥, kù 𒆬, ku4 𒆭 lá=LAL 𒇲, là=NU 𒉡 lé=NI 𒉌 lí=NI 𒉌 lú 𒇽 ál=ALAM 𒀩 él=IL 𒅋 íl 𒅍 úl=NU 𒉡 má 𒈣 mé=MI 𒈪, mè 𒀞/𒅠 mí=MUNUS 𒊩, mì=ME 𒈨 mú=SAR 𒊬 ám=ÁG 𒉘 ím=KAŠ4 𒁽 úm=UD 𒌓 ná 𒈿, nà=AG 𒀝, na4 ("NI.UD") 𒉌𒌓 né=NI 𒉌 ní=IM 𒉎 nú=NÁ 𒈿 én 𒋙𒀭, èn=LI 𒇷 in4=EN 𒂗, in5=NIN 𒊩𒌆 ún=U 𒌋 pá=BA 𒁀, pà=PAD3 𒅆𒊒 pé=BI 𒁉 pí=BI 𒁉, pì=BAD 𒁁 pú=TÚL 𒇥, pù 𒅤 ép=TUM 𒌈 íp=TUM 𒌈 úp=ŠÈ 𒂠 rá=DU 𒁺 ré=URU 𒌷, rè=LAGAB 𒆸 rí=URU 𒌷 rì=LAGAB 𒆸 rú=GAG 𒆕, rù=AŠ 𒀸 ár=UB 𒌒 ír=A.IGI 𒀀𒅆 úr 𒌫 sá=DI 𒁲, sà=ZA 𒍝, sa4 ("ḪU.NÁ") 𒄷𒈾 sé=ZI 𒍣 sí=ZI 𒍣 sú=ZU 𒍪, sù=SUD 𒋤, su4 𒋜 és=EŠ 𒂠 ís=EŠ 𒂠 ús=UŠ 𒍑, us₅ 𒇇 šá=NÍG 𒐼, šà 𒊮 šé, šè 𒂠 ší=SI 𒋛 šú 𒋙, šù=ŠÈ 𒂠, šu4=U 𒌋 áš 𒀾 éš=ŠÈ 𒂠 íš=KASKAL 𒆜 úš=BAD 𒁁 tá=DA 𒁕 té=TÍ 𒊹 tí 𒊹, tì=DIM 𒁴, ti4=DI 𒁲 tú=UD 𒌓, tù=DU 𒁺 át=GÍR gunû 𒄉 út=ÁŠ 𒀾 zá=NA4 𒉌𒌓 zé=ZÍ 𒍢 zí 𒍢, zì 𒍥 zú=KA 𒅗 éz=EŠ 𒂠 íz=IŠ 𒅖 úz=UŠ 𒍑, ùz 𒍚 This text was inscribed on a small clay cone c. 2400 BC.

(RIME 1.09.05.01)[555] 𒀭𒂗𒆤den-lil2𒈗lugal𒆳𒆳𒊏kur-kur-ra𒀊𒁀ab-ba𒀭𒀭𒌷𒉈𒆤dig̃ir-dig̃ir-re2-ne-ke4𒅗inim𒄀𒈾𒉌𒋫gi-na-ni-ta𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄈𒋢dnin-g̃ir2-su𒀭𒇋𒁉dšara2-bi𒆠ki𒂊𒉈𒋩e-ne-sur𒀭𒂗𒆤 𒈗 𒆳𒆳𒊏 𒀊𒁀 𒀭𒀭𒌷𒉈𒆤 𒅗 𒄀𒈾𒉌𒋫 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄈𒋢 𒀭𒇋𒁉 𒆠 𒂊𒉈𒋩den-lil2 lugal kur-kur-ra ab-ba dig̃ir-dig̃ir-re2-ne-ke4 inim gi-na-ni-ta dnin-g̃ir2-su dšara2-bi ki e-ne-sur"Enlil, king of all the lands, father of all the gods, by his firm command, fixed the border between Ningirsu and Šara.

"𒈨𒁲me-silim𒈗lugal𒆧𒆠𒆤kiški-ke4𒅗inim𒀭𒅗𒁲𒈾𒋫dištaran-na-ta𒂠eš2𒃷gana2𒁉𒊏be2-ra𒆠𒁀ki-ba𒈾na𒉈𒆕bi2-řu2𒈨𒁲 𒈗 𒆧𒆠𒆤 𒅗 𒀭𒅗𒁲𒈾𒋫 𒂠 𒃷 𒁉𒊏 𒆠𒁀 𒈾 𒉈𒆕me-silim lugal kiški-ke4 inim dištaran-na-ta eš2 gana2 be2-ra ki-ba na bi2-řu2"Mesilim, king of Kiš, at the command of Ištaran, measured the field and set up a stele there.

"𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄈𒋢dnin-g̃ir2-su𒌨𒊕ur-sag𒀭𒂗𒆤𒇲𒆤den-lil2-la2-ke4𒅗inim𒋛𒁲𒉌𒋫si-sa2-ni-ta𒄑𒆵𒆠𒁕ummaki-da𒁮𒄩𒊏dam-ḫa-ra𒂊𒁕𒀝e-da-ak𒀭𒊩𒌆𒄈𒋢 𒌨𒊕 𒀭𒂗𒆤𒇲𒆤 𒅗 𒋛𒁲𒉌𒋫 𒄑𒆵𒆠𒁕 𒁮𒄩𒊏 𒂊𒁕𒀝dnin-g̃ir2-su ur-sag den-lil2-la2-ke4 inim si-sa2-ni-ta ummaki-da dam-ḫa-ra e-da-ak"Ningirsu, warrior of Enlil, at his just command, made war with Umma.

"𒅗inim𒀭𒂗𒆤𒇲𒋫den-lil2-la2-ta𒊓sa𒌋šu4𒃲gal𒉈𒌋bi2-šu4𒅖𒇯𒋺𒁉SAḪAR.DU6.TAKA4-bi𒂔𒈾eden-na𒆠ki𒁀𒉌𒍑𒍑ba-ni-us2-us2𒅗 𒀭𒂗𒆤𒇲𒋫 𒊓 𒌋 𒃲 𒉈𒌋 𒅖𒇯𒋺𒁉 𒂔𒈾 𒆠 𒁀𒉌𒍑𒍑inim den-lil2-la2-ta sa šu4 gal bi2-šu4 SAḪAR.DU6.TAKA4-bi eden-na ki ba-ni-us2-us2"At Enlil's command, he threw his great battle net over it and heaped up burial mounds for it on the plain.