Sumitro Djojohadikusumo

Returning to Indonesia after the war, he was assigned to the country's diplomatic mission in the United States, where he sought to raise funds and garner international attention in the struggle against Dutch colonialism.

After the handover of sovereignty as a result of the 1949 Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference, in which he took part, he joined the Socialist Party and became Minister for Trade and Industry in the Natsir Cabinet.

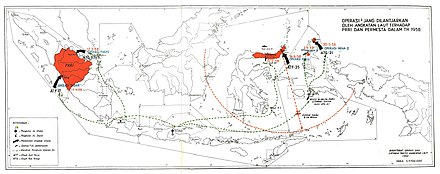

Due to political differences and allegations of corruption, Sumitro fled Jakarta and joined the insurrectionary Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia in the late 1950s.

Considered a leader of the movement, he operated from abroad, liaising with Western foreign intelligence organizations while seeking funds and international support.

He was the eldest child of Margono Djojohadikusumo, a high ranking civil servant in the colonial government of the Dutch East Indies and later founder of Bank Negara Indonesia,[1][2] and Siti Katoemi Wirodihardjo.

[15][16][17] According to British reports, Sumitro had been included in the delegation to provide a good impression for the Dutch government, but he became disillusioned and decided to return to his home country.

[20] By this time Dutch forces under the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration had returned to Indonesia to retake control, but they had managed to hold only several coastal cities at first.

[22][23] Later in 1946 Sumitro was assigned to the Indonesian observer delegation to the United Nations as deputy chief of mission and minister plenipotentiary for economic affairs,[2][24] while he unofficially engaged in fundraising.

"[26] While in the United States, Sumitro also signed a contract with American businessman Matthew Fox to form the Indonesian–American corporation, an agent for bilateral trade of several commodities between the two countries with a ten-year licence.

[24] Previously the Indonesian delegation had been ignored, but the military operation brought Indonesia to the forefront of attention, and after a meeting with Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett, Sumitro gave a press conference which was prominently featured in American media.

The New York Times, for example, published in its entirety a memorandum from Sumitro condemning Dutch actions and calling for the cessation of American aid (i.e. the Marshall Plan) to the Netherlands.

[38] After the handover of sovereignty, Sumitro was appointed as Minister of Trade and Industry in the newly formed Natsir Cabinet as a member of Sutan Sjahrir's Socialist Party of Indonesia (PSI).

Sumitro introduced the "Economic Urgency Plan" which aimed to restore industrial facilities that had been damaged by the Japanese invasion and the subsequent war of independence.

[53] In mid-1951, he also invited Hjalmar Schacht, the former finance minister of Nazi Germany, to Indonesia to research the country's economic and financial situation, and to produce recommendations.

[63] When he first joined the finance ministry, which at that time still included many Dutch officials left from the colonial era, he noted how many of them were skilled administrators who were not qualified in economics.

[83] In a 1952 paper Sumitro indicated the objectives of his policies – to stimulate domestic consumption and investment and improve Indonesia's trade balance – and commented that due to the poor administrative capabilities of the Indonesian government it should avoid direct interventions in the economy.

Aidit rejected Sumitro's argument that poverty was caused by low investment and savings, and instead blamed capitalists, landlords, and foreign companies for engaging in rent-seeking behaviour.

[93] The council was formed by provincial military commanders such as Husein who were dissatisfied with Sukarno's increasing centralization of power, and had been demanding regional autonomy since its formation in late 1956.

[93] Other civilian leaders, such as Masyumi's Sjafruddin Prawiranegara and Burhanuddin Harahap later also escaped prosecution to West Sumatra and joined Sumitro and the Banteng Council.

The meeting was arranged by South Sumatra's military commander Colonel Barlian [id], who hoped to find a compromise between the dissidents and the Jakarta government.

[121] He corresponded with anti-communist military officers during the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, and supported an attempt to revive the banned PSI although many of his former party colleagues viewed him negatively due to his participation in the rebellion.

By the middle of the month, accepting that the tour had been a failure, Sumitro instead warned the students that any attempt to create a political movement would be dealt with "sternly".

[149] By the early 1980s, the Indonesian state-owned enterprises' role in the economy had been scaled down in favour of increased private sector participation to the extent that Sumitro had advised.

When the Asian financial crisis struck Indonesia late in the decade, Sumitro blamed institutional problems and corruption for the impact and called for "immediate and firm action".

[151] Though his influence in government policymaking was diminished, he continued to play a role in politics, supporting the unsuccessful attempt to nominate Emil Salim as vice-president in early 1998.

[156] To accomplish this, Sumitro wrote in support of foreign investments, with caveats on domestic capital and labour participation, human development, and reinvestment of profits within Indonesia.

[157] Though he disliked the enforcement of quotas and restrictions on trade, he acknowledged that it was politically impossible for Indonesia during his time to engage in a complete free-market economic regime.

[174] His critics describe him as a political opportunist, due to his distancing from former Socialist Party members during the Suharto period and his son Prabowo's marriage to Titiek.

[175] Indonesian academic Vedi R. Hadiz [id] noted that although Sumitro's economic thought could not be described as "liberal", he strongly opposed Sukarno's anti-capitalist stance.

[176] Sumitro's role in Indonesia's early formation and his economic policies have prominently featured in the electoral campaigns of his son's political party, Gerindra.