Mass (liturgy)

Fortescue (1910) cites older, "fanciful" etymological explanations, notably a latinization of Hebrew matzâh (מַצָּה) "unleavened bread; oblation", a derivation favoured in the 16th century by Reuchlin and Luther, or Greek μύησις "initiation", or even Germanic mese "assembly".

[a] The French historian Du Cange in 1678 reported "various opinions on the origin" of the noun missa "Mass", including the derivation from Hebrew matzah (Missah, id est, oblatio), here attributed to Caesar Baronius.

[10] Thus, De divinis officiis (9th century)[11] explains the word as "a mittendo, quod nos mittat ad Deo" ("from 'sending', because it sends us towards God"),[12] while Rupert of Deutz (early 12th century) derives it from a "dismissal" of the "enmities which had been between God and men" ("inimicitiarum quæ erant inter Deum et homines").

[14] The Catholic Church sees the Mass or Eucharist as "the source and summit of the Christian life", to which the other sacraments are oriented.

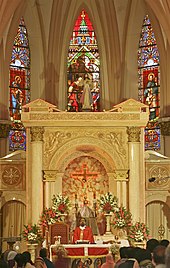

The ordained celebrant (priest or bishop) is understood to act in persona Christi, as he recalls the words and gestures of Jesus Christ at the Last Supper and leads the congregation in praise of God.

[18][19] In a 1993 letter to Bishop Johannes Hanselmann of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) affirmed that "a theology oriented to the concept of succession [of bishops], such as that which holds in the Catholic and in the Orthodox church, need not in any way deny the salvation-granting presence of the Lord [Heilschaffende Gegenwart des Herrn] in a Lutheran [evangelische] Lord's Supper".

[20] The Decree on Ecumenism, produced by Vatican II in 1964, records that the Catholic Church notes its understanding that when other faith groups (such as Lutherans, Anglicans, and Presbyterians) "commemorate His death and resurrection in the Lord's Supper, they profess that it signifies life in communion with Christ and look forward to His coming in glory".

[19] Within the fixed structure outlined below, which is specific to the Roman Rite, the Scripture readings, the antiphons sung or recited during the entrance procession or at Communion, and certain other prayers vary each day according to the liturgical calendar.

Of the options offered for the Introductory Rites, that preferred by liturgists would bridge the praise of the opening hymn with the Glory to God which follows.

If there are three readings, the first is from the Old Testament (a term wider than "Hebrew Scriptures", since it includes the Deuterocanonical Books), or the Acts of the Apostles during Eastertide.

On all Sundays and Holy Days of Obligation, and preferably at all Masses, a homily or sermon that draws upon some aspect of the readings or the liturgy itself, is then given.

With the liturgical renewal following the Second Vatican Council, numerous other Eucharistic prayers have been composed, including four for children's Masses.

Central to the Eucharist is the Institution Narrative, recalling the words and actions of Jesus at his Last Supper, which he told his disciples to do in remembrance of him.

[32] Since the early church an essential part of the Eucharistic prayer has been the epiclesis, the calling down of the Holy Spirit to sanctify our offering.

[33] The priest concludes with a doxology in praise of God's work, at which the people give their Amen to the whole Eucharistic prayer.

The priest introduces it with a short phrase and follows it up with a prayer called the embolism, after which the people respond with another doxology.

The sign of peace is exchanged and then the "Lamb of God" ("Agnus Dei" in Latin) litany is sung or recited while the priest breaks the host and places a piece in the main chalice; this is known as the rite of fraction and commingling.

Blessed are those called to the supper of the Lamb," to which all respond: "Lord, I am not worthy that you should enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed."

[36] Singing by all the faithful during the Communion procession is encouraged "to express the communicants' union in spirit"[37] from the bread that makes them one.

Luther composed as a replacement a revised Latin-language rite, Formula missae, in 1523, and the vernacular Deutsche Messe in 1526.

The bishops and pastors of the larger Lutheran bodies have strongly encouraged this restoration of the weekly Mass.

The various Eucharistic liturgies used by national churches of the Anglican Communion have continuously evolved from the 1549 and 1552 editions of the Book of Common Prayer, both of which owed their form and contents chiefly to the work of Thomas Cranmer, who in about 1547 had rejected the medieval theology of the Mass.

[46] In the 1552 revision, this was made clear by the restructuring of the elements of the rite while retaining nearly all the language so that it became, in the words of an Anglo-Catholic liturgical historian (Arthur Couratin) "a series of communion devotions; disembarrassed of the Mass with which they were temporarily associated in 1548 and 1549".