Superhero

Some superheroes (for example, Batman and Iron Man) derive their status from advanced technology they create and use, while others (such as Superman and Spider-Man) possess non-human or superhuman biology or use and practice magic to achieve their abilities (such as Captain Marvel and Doctor Strange).

Antecedents of the archetype include mythological characters such as Gilgamesh, Hanuman, Perseus, Odysseus, David, and demigods like Heracles, all of whom were blessed with extraordinary abilities, which later inspired the superpowers that became a fundamental aspect of modern-day superheroes.

[21] In August 1937, in a letter column of the pulp magazine Thrilling Wonder Stories, the word superhero was used to define the title character of the comic strip Zarnak, by Max Plaisted.

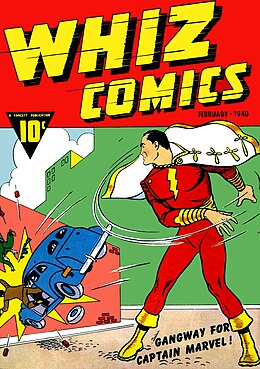

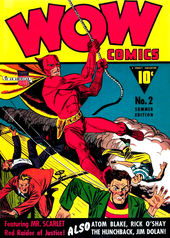

[22][23] In the 1930s, the trends converged in some of the earliest superpowered costumed heroes, such as Japan's Ōgon Bat (1931) and Prince of Gamma (early 1930s), who first appeared in kamishibai (a kind of hybrid media combining pictures with live storytelling),[24][25] Mandrake the Magician (1934),[26][27][28] Olga Mesmer (1937)[29] and then Superman (1938) and Captain Marvel (1939) at the beginning of the Golden Age of Comic Books, whose span, though disputed, is generally agreed to have started with Superman's launch.

[45] Modeled from the myth of the Amazons of Greek mythology, she was created by psychologist William Moulton Marston, with help and inspiration from his wife Elizabeth and their mutual lover Olive Byrne.

Being built from an incomplete robot originally intended for military purposes, Astro Boy possessed amazing powers such as flight through thrusters in his feet and the incredible mechanical strength of his limbs.

[48] Created by Kōhan Kawauchi, he followed up its success with the tokusatsu superhero shows Seven Color Mask (1959) and Messenger of Allah (1960), both starring a young Sonny Chiba.

Typically the superhero supergroups featured at least one (and often the only) female member, much like DC's flagship superhero team the Justice League of America (whose initial roster included Wonder Woman as the token female); examples include the Fantastic Four's Invisible Girl, the X-Men's Jean Grey (originally known as Marvel Girl), the Avengers' Wasp, and the Brotherhood of Mutants' Scarlet Witch (who later joined the Avengers) with her brother, Quicksilver.

1966 saw the debut of the sci-fi/horror series Ultra Q created by Eiji Tsuburaya this would eventually lead to the sequel Ultraman, spawning a successful franchise which pioneered the Kyodai Hero subgenre where the superheroes would be as big as giant monsters (kaiju) that they fought.

The 1970s would see more anti-heroes introduced into Superhero fiction such examples included the debut of Shotaro Ishinomori's Skull Man (the basis for his later Kamen Rider) in 1970, Go Nagai's Devilman in 1972 and Gerry Conway and John Romita's Punisher in 1974.

The ideas of second-wave feminism, which spread through the 1960s into the 1970s, greatly influenced the way comic book companies would depict as well as market their female characters: Wonder Woman was for a time revamped as a mod-dressing martial artist directly inspired by the Emma Peel character from the British television series The Avengers (no relation to the superhero team of the same name),[53] but later reverted to Marston's original concept after the editors of Ms. magazine publicly disapproved of the character being depowered and without her traditional costume;[54] Supergirl was moved from being a secondary feature on Action Comics to headline Adventure Comics in 1969; the Lady Liberators appeared in an issue of The Avengers as a group of mind-controlled superheroines led by Valkyrie (actually a disguised supervillainess) and were meant to be a caricatured parody of feminist activists;[55] and Jean Grey became the embodiment of a cosmic being known as the Phoenix Force with seemingly unlimited power in the late 1970s, a stark contrast from her depiction as the weakest member of her team a decade ago.

[56] Female supporting characters who were successful professionals or hold positions of authority in their own right also debuted in the pages of several popular superhero titles from the late 1950s onward: Hal Jordan's love interest Carol Ferris was introduced as the Vice-President of Ferris Aircraft and later took over the company from her father; Medusa, who was first introduced in the Fantastic Four series, is a member of the Inhuman Royal Family and a prominent statesperson within her people's quasi-feudal society; and Carol Danvers, a decorated officer in the United States Air Force who would become a costumed superheroine herself years later.

In subsequent decades, popular characters like Dazzler, She-Hulk, Elektra, Catwoman, Witchblade, Spider-Girl, Batgirl and the Birds of Prey became stars of long-running eponymous titles.

[68] In 1972, Mego Corporation, an American toy company, attempted to register the mark "World's Greatest Superheroes" in connection with its line of action figures.

[74] Now, the two publishers jointly own numerous trademarks for figurines (see Spider-Man, Batman), movies, TV shows, magazines, merchandise, cardboard stand-up figures, playing cards, erasers, pencils, notebooks, cartoons, and many more.

[74] For instance, the companies filed a trademark application as joint owners for the mark "SUPER HEROES" for a series of animated motion pictures in 2009 (Reg.

[77] In 2019, the companies pursued a British law student named Graham Jules who was attempting to publish a self-help book titled Business Zero to Superhero.

Courts have noted that determining whether a term has become generic is a highly factual inquiry not suitable for resolution without considering evidence like dictionary definitions, media usage, and consumer surveys.

Beginning in the 1960s with the civil rights movement in the United States, and increasingly with the rising concern over political correctness in the 1980s, superhero fiction centered on cultural, ethnic, national, racial and language minority groups (from the perspective of US demographics) began to be produced.

Women are presented differently than their male counterparts, typically wearing revealing clothing that showcases their curves and cleavage and showing a lot of skin in some cases.

[102][103] The female characters in comic books are used to satisfy male desire for the "ideal" woman (small waist, large breasts, toned, athletic body).

[105] Wonder Woman has been subject to a long history of suppression as a result of her strength and power, including American culture's undoing of the Lynda Carter television series.

In 1989, the Monica Rambeau incarnation of Captain Marvel was the first female black superhero from a major publisher to get her own title in a special one-shot issue.

[111] In 1973, Shang-Chi became the first prominent Asian superhero to star in an American comic book (Kato had been a secondary character of the Green Hornet media franchise series since its inception in the 1930s.[112]).

The X-Men, in particular, were revived in 1975 with a line-up of characters drawn from several nations, including the Kenyan Storm, German Nightcrawler, Soviet/Russian Colossus, Irish Banshee, and Japanese Sunfire.

Her self-titled comic book series became a cultural phenomenon, with extensive media coverage by CNN, the New York Times and The Colbert Report, and embraced by anti-Islamophobia campaigners in San Francisco who plastered over anti-Muslim bus adverts with Kamala stickers.

[114] Other such successor-heroes of color include James "Rhodey" Rhodes as Iron Man and to a lesser extent Riri "Ironheart" Williams, Ryan Choi as the Atom, Jaime Reyes as Blue Beetle and Amadeus Cho as Hulk.

Examples include the Mikaal Tomas incarnation of Starman in 1998; Colossus in the Ultimate X-Men series; Renee Montoya in DC's Gotham Central series in 2003; the Kate Kane incarnation of Batwoman in 2006; Rictor and Shatterstar in an issue of X-Factor in 2009; the Golden Age Green Lantern Alan Scott is reimagined as openly gay following The New 52 reboot in 2011;[117][118] and in 2015, a younger time displaced version of Iceman in an issue of All-New X-Men.

[119] Many new openly gay, lesbian and bisexual characters have since emerged in superhero fiction, such as Gen13's Rainmaker, Apollo and Midnighter of The Authority, and Wiccan and Hulkling of the Young Avengers.

[124] An animated short The Ambiguously Gay Duo parodies comic book superheroes and features Ace and Gary (Stephen Colbert, Steve Carell).