Blockbuster (entertainment)

The term has also come to refer to any large-budget production intended for "blockbuster" status, aimed at mass markets with associated merchandising, sometimes on a scale that meant the financial fortunes of a film studio or a distributor could depend on it.

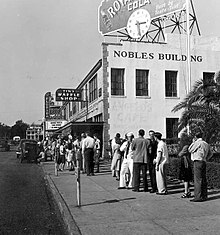

Another explanation is that trade publications would often advertise the popularity of a film by including illustrations showing long queues often extending around the block, but in reality the term was never used in this way.

According to Prince, Kurosawa became "a mentor figure" to a generation of emerging American filmmakers who went on to develop the Hollywood blockbuster format in the 1970s, such as Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola.

[10] Alongside other films from the New Hollywood era, George Lucas's 1973 hit American Graffiti is often cited for helping give birth to the summer blockbuster.

[12][13][14][15][16][17] Some examples of summer blockbusters from the 2000s include Ice Age (2002),[18] Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003), The Da Vinci Code (2006), Transformers (2007) and Iron Man (2008)[19]—all of which founded successful franchises—and originals like Shrek (2001),[20] The Day After Tomorrow (2004) and Pixar's Finding Nemo (2003), WALL-E (2008) and Up (2009).

Several established franchises continued to spawn successful entries with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 (2011), X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014), Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017), Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018) and Frozen II (2019) and Pixar's Toy Story 3 (2010) and Incredibles 2 (2018) alongside animated originals Zootopia (2016) and Inside Out (2015).

This view is taken, for example, by film journalist Peter Biskind, who wrote that all studios wanted was another Jaws, and as production costs rose, they were less willing to take risks, and therefore based blockbusters on the "lowest common denominators" of the mass market.

[42] Peter Biskind's book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls argues that the New Hollywood movement marked a significant shift towards independently produced and innovative works by a new wave of directors, but that this shift began to reverse itself when the commercial success of Jaws and Star Wars led to the realization by studios of the importance of blockbusters, advertising and control over production (even though the success of The Godfather was said to be the precursor to the blockbuster phenomenon).