Normal (geometry)

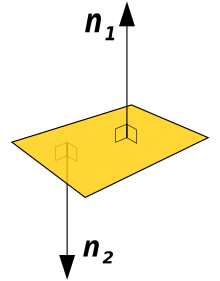

Multiplying a normal vector by −1 results in the opposite vector, which may be used for indicating sides (e.g., interior or exterior).

The concept of normality generalizes to orthogonality (right angles).

The concept has been generalized to differentiable manifolds of arbitrary dimension embedded in a Euclidean space.

is the set of vectors which are orthogonal to the tangent space at

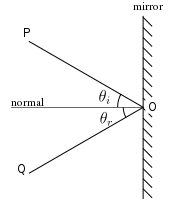

The normal is often used in 3D computer graphics (notice the singular, as only one normal will be defined) to determine a surface's orientation toward a light source for flat shading, or the orientation of each of the surface's corners (vertices) to mimic a curved surface with Phong shading.

The foot of a normal at a point of interest Q (analogous to the foot of a perpendicular) can be defined at the point P on the surface where the normal vector contains Q.

The normal distance of a point Q to a curve or to a surface is the Euclidean distance between Q and its foot P. The normal direction to a space curve is: where

is the tangent vector, in terms of the curve position

: For a convex polygon (such as a triangle), a surface normal can be calculated as the vector cross product of two (non-parallel) edges of the polygon.

real variables, then a normal to S is by definition a normal to a tangent plane, given by the cross product of the partial derivatives

since the gradient at any point is perpendicular to the level set

an upward-pointing normal can be found either from the parametrization

Since a surface does not have a tangent plane at a singular point, it has no well-defined normal at that point: for example, the vertex of a cone.

In general, it is possible to define a normal almost everywhere for a surface that is Lipschitz continuous.

The normal to a (hyper)surface is usually scaled to have unit length, but it does not have a unique direction, since its opposite is also a unit normal.

For an oriented surface, the normal is usually determined by the right-hand rule or its analog in higher dimensions.

If the normal is constructed as the cross product of tangent vectors (as described in the text above), it is a pseudovector.

perpendicular to the transformed tangent plane

The inverse transpose is equal to the original matrix if the matrix is orthonormal, that is, purely rotational with no scaling or shearing.

Alternatively, if the hyperplane is defined as the solution set of a single linear equation

The definition of a normal to a surface in three-dimensional space can be extended to

A hypersurface may be locally defined implicitly as the set of points

At these points a normal vector is given by the gradient:

The normal line is the one-dimensional subspace with basis

A differential variety defined by implicit equations in the

By the implicit function theorem, the variety is a manifold in the neighborhood of a point where the Jacobian matrix has rank

The normal (affine) space at a point

and generated by the normal vector space at

These definitions may be extended verbatim to the points where the variety is not a manifold.

Thus the normal affine space is the plane of equation