Susie King Taylor

Beyond her aptitude in nursing the wounded of the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry Regiment, Taylor was the first Black woman to self-publish her memoirs.

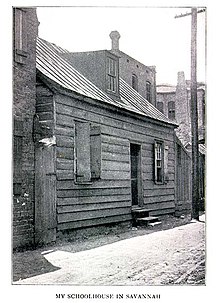

Susie Baker attended school with about 25 to 30 children for another two years, after which she would find instruction from another free woman of color, Mrs. Mathilda Beasley.

Susie Baker became friends with a white playmate named Katie O’Connor, who attended a Savannah convent school.

Lastly, Susie would be educated by the son of Dolly Reed's white landlord until he was called to military duty for the Confederacy: James Blouis, our landlord's son, was attending the High School, and was very fond of grandmother, so she asked him to give me a few lessons, which he did until the middle of 1861, when the Savannah Volunteer Guards, to which he and his brother belonged, were ordered to the front under General Barton.

In the first battle of Manassas, his brother Eugene was killed, and James deserted over to the Union side, and at the close of the war went to Washington, D.C., where he has since resided.

As a youngster, Susie Baker wrote town passes that gave some amount of security to Black people who were out on the street after the curfew bell was rung at nine o’clock each night.

Despite being exposed to secessionist propaganda that attempted to paint all people from the North as wanting to further subjugate the Black population, young Susie Baker soon saw the importance of supporting the Union in the war.

[citation needed] In late August 1862, Captain Charles T. Trowbridge came to St. Simon's Island by order of General David Hunter, a noted abolitionist.

[10] In her memoir published in 1902, Susie King Taylor shared many of the gruesome sights she encountered during the war and expresses her willingness to help the wounded.

[6] In a letter to Susie from Colonel C. T. Trowbridge, an officer of the 33rd regiment, he mentions that she is unable to acquire a federal pension, as she was an army nurse.

[6] In February 1862, she wrote about assisting a male nurse in the same military company during the war: Edward Davis had contracted varioloid, a form of smallpox that sometimes occurs when one is vaccinated against the disease.

Taylor visited the hospital at Camp Shaw in Beaufort, South Carolina where Barton worked, and would help tend the wounded and sick.

[1] After the American Civil War ended and the Reconstruction era began, Susie and her husband Edward King left the 33rd regiment and returned to Savannah.

[5] In September 1866, just months before the birth of his child with Susie, Edward King died in a docking accident while he worked as a longshoreman.

Susie placed her baby in her mother's care and took the only job available—as a domestic servant to Mr. and Mrs. Charles Green, a wealthy white family.

[7] In 1870, she traveled with the Greens to Boston for the summer, and while there, she won a prize for her excellent cooking at the fundraiser the ladies held to raise funds to build a new Episcopal church.

[6] During the Reconstruction era, Taylor became a civil rights activist after witnessing much discrimination in the South, where Jim Crow and the Ku Klux Klan mocked and terrorized African Americans.

[14] In October 2021, Boston mayor Kim Janey dedicated a new memorial headstone inscribed with Ms. Taylor's name and likeness.

[15] In 2018, Taylor was elected posthumously to the Georgia Women of Achievement Hall of Fame (HOF) for her contributions to education, freedom, and humanity during her lifetime.

Erected in 2019 near the Midway First Presbyterian Church by the Georgia Historical Society, the official state marker commemorates Taylor's lifelong contributions to formal education, literature, and medicine.

[16] The Susie King Taylor Women's Institute and Ecology Center was established in 2015 in Midway by historian Hermina Glass-Hill.