Sutton Hoo helmet

[17][18] The preferred candidate, with some exceptions when the burial was thought to have taken place later,[19][20] has been Rædwald;[21] his kingdom, East Anglia, is believed to have had its seat at Rendlesham, 4+1⁄4 miles (6.8 kilometres) upriver from Sutton Hoo.

[22][23] The case for Rædwald, by no means conclusive, rests on the dating of the burial, the abundance of wealth and items identified as regalia, and, befitting a king who kept two altars, the presence of both Christian and pagan influences.

[21] In their respective works Flores Historiarum and Chronica Majora, the thirteenth-century historians Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris appear to place Tytila's death, and Rædwald's presumed concurrent succession to the throne, in 599.

[28][29] In any event, Rædwald would have ascended to power by at least 616, around when Bede records him as raising an army on behalf of Edwin of Northumbria and defeating Æthelfrith in a battle on the east bank of the River Idle.

[87] The so-called wand or rod, surviving only as a 96 mm (3.8 in) gold and garnet strip with a ring at the top, associated mountings, and traces of organic matter that may have been wood, ivory, or bone, has no discernible use but as a symbol of office.

[89] Its delicate ornamentation, including a carved head with a modified eye that parallels the possible allusion to Odin on the helmet,[90] suggests that it too was a ceremonial object, and it has been tentatively identified as a sceptre.

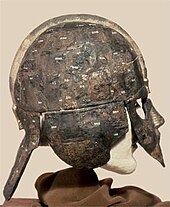

[190][191] Excepting the portions covered by the eyebrows and dragon head,[151] or adorned with silver or niello,[note 11] the nose and mouth piece was heavily gilded,[183][189] which is suggested by the presence of mercury to have been done with the fire-gilding method.

[196][note 12] Gilding on the dexter eyebrow was "reddish in colour" against the "yellowish" hue of the sinister,[198] while the latter contains both trace amounts of mercury and a tin corrosion product which are absent from its counterpart.

The sixth fragment is placed in the middle row of the dexter cheek guard, on the panel closest to the face mask;[216][217] the generally symmetrical nature of the helmet implies the design's position on the opposite side as well.

[277] Fragment (a) for example shows groups of parallel raised lines running in correspondence "with changes of angle or direction in the modelled surface, which on the analogy of the Sutton Hoo and other rider scenes in Vendel art, strongly suggest the body of a horse.

[293] As it is older than the man with whom it was buried, the helmet may have been an heirloom,[294][284] symbolic of the ceremonies of its owner's life and death;[295][296][297] it may further be a progenitor of crowns, known in Europe since around the twelfth century,[298][299] indicating both a leader's right to rule and his connection with the gods.

[313] Helmets are relatively common in Beowulf, an Anglo-Saxon poem focused on royals and their aristocratic milieu,[314][315][316] but rarely found today; only six are currently known, despite the excavation of thousands of graves from the period.

[340] At the same time, the helmet shares "consistent and intimate" parallels with those characterised in the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf,[341] and, like the Sutton Hoo ship-burial as a whole,[342] has had a profound impact on modern understandings of the poem.

"[492] Its appearance is substantially more similar to the Staffordshire helmet, which, while still undergoing conservation, has "a pair of cheek pieces cast with intricate gilded interlaced designs along with a possible gold crest and associated terminals.

[581] Unlike on the Sutton Hoo helmet, the Valsgärde 7 rider and fallen warrior design was made with two dies, so that those on both dexter and sinister sides are seen moving towards the front, and they contain some "differing and additional elements.

[595] The neck guard similarly assumes leather hinges,[596][note 20] and with its solid iron construction—like the one-piece cap, unique among Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian helmets[598]—is even more closely aligned with the Roman examples,[599] if longer than was typical.

Ymb þæs helmes hrof heafodbeorge wirum bewunden wala utan heold, þæt him fela laf frecne ne meahton scurheard sceþðan, þonne scyldfreca ongean gramum gangan scolde.

"[520][302] The discovery has led many Old English dictionaries to define wala within the "immediate context" of Beowulf, including as a "ridge or comb inlaid with wires running on top of helmet from front to back," although doing so "iron[s] out the figurative language" intended in the poem.

"[409] In Beowulf, "a poem about kings and nobles, in which the common people hardly appear,"[330] compounds such as "battle-mask" (beadogriman[673]), "war-mask" (heregriman[674]), "mask-helm" (grimhelmas[675]), and "war-head" (wigheafolan[676]) indicate the use of visored helmets.

[12] The discovery was recorded in the diary of C. W. Phillips as follows: Friday, 28 July 1939: "The crushed remains of an iron helmet were found four feet [1.2 m] east of the shield boss on the north side of the central deposit.

"[687] Despite scant time to examine the fragments,[688][689] they were termed "elaborate"[690] and "magnificent";[691] "crushed and rotted"[692] and "sadly broken" such that it "may never make such an imposing exhibit as it ought to do,"[693] it was nonetheless thought the helmet "may be one of the most exciting finds.

[694][693][695][696][697] Under the common law in effect at the time, gold and silver that had been hidden and later rediscovered, with the original ownership undetermined, was declared treasure trove, and thus the property of the crown.

[716] Throughout World War II the Sutton Hoo artefacts, along with other treasures from the British Museum such as the Elgin Marbles,[717][718] were stored in the tunnel connecting the Aldwych and Holborn tube stations.

[722] His job was to restore and conserve the finds from the Sutton Hoo ship-burial, including what Bruce-Mitford called "the real headaches – notably the crushed shield, helmet and drinking horns".

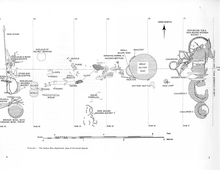

[733] An artistic reconstruction created in 1966 by the British Museum and the Archaeology Division of the Ordnance Survey, under the direction of C. W. Phillips,[756][757] attempted to solve some of these problems, showing a larger cap, a straighter face mask, smaller eye openings, the terminal dragon heads at opposite ends, and the rearrangement of some of the pressblech panels.

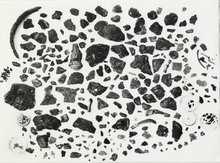

Among other objectives were to survey the burial mound and its surrounding environment, to relocate the ship impression (from which a plaster cast was ultimately taken[761][762][763]) and excavate underneath, and to search the strata from the 1939 dumps for any fragments that may have been originally missed.

[764][765][766] The first excavation had effectively been a rescue dig under the threat of impending war,[767][768] creating the danger that fragments of objects might have been inadvertently discarded;[765][769] a gold mount from the burial was already known to have nearly met that fate.

[804][805] Although termed "masterful" and "universally acclaimed" by contemporaries,[806][777] the current reconstruction of the Sutton Hoo helmet left "a number of minor problems unsolved"[618] and contains several slight inaccuracies.

[814][815] The museum provided a general blueprint of the design[619] along with electrotypes of the decorative elements—nose and mouth piece, eyebrows, dragon heads, and pressblech foils—leaving the Master of the Armouries A. R. Duffy, along with his assistant H. Russell Robinson and senior conservation officer armourers E. H. Smith and A. Davis to complete the task.

[618][816] A number of differences in construction were observed, such as a solid crest, lead solder used to back the decorative effects, and the technique employed to inlay the silver, although the helmet hewed closely to the original design.