Holy Crown of Hungary

According to popular tradition, St Stephen I held up the crown before his death (in the year 1038) to consecrate it and his kingdom to the Virgin Mary.

According to the most accepted theory, in the publications of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and the Hungarian Catholic Episcopal Conference,[7] the Holy Crown consists of three parts: the lower abroncs (rim, hoop), the corona graeca; the upper keresztpántok (cross straps), the corona latina; and the uppermost cross, tilted at an angle.

According to "Hartvik’s legend", St. Stephen sent Archbishop Astrik of Esztergom to Rome to acquire a crown from the "Pope", who is not named.

Hartvik’s legend appeared in liturgical books and breviaries in Hungary around 1200, naming the then-existing Pope Sylvester II.

Also, the "Greater Legend" of St Stephen, written around 1083, makes no mention of the Crown's Roman provenance: "in the fifth year after the death of his father...they brought a Papal letter of blessing...and the Lord’s favoured one, Stephen, was chosen to be king, and was anointed with oil and auspiciously crowned with the diadem of royal honour".

Another document giving doubtful evidence is by Thietmar von Merseburg (died 1018): he wrote that Holy Roman Emperor Otto III consented to Stephen's coronation, and that the Pope sent his blessings, but there is no mention of a crown.

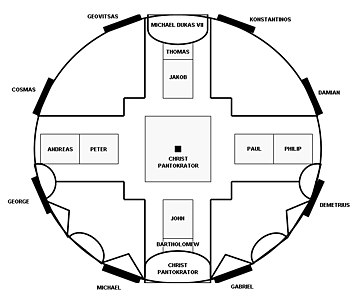

The Holy Crown was made of gold and decorated with nineteen enamel "pantokrator" pictures (Greek meaning "master of all") as well as semi-precious stones, genuine pearls, and almandine.

The two aquamarine stones with cut surfaces on the back of the diadem were added as replacements by King Matthias II (1608–1619).

On the rim to the right and left of Jesus are pictures of the archangels Michael and Gabriel, followed by half-length images of the Saints George and Demetrius, and Cosmas and Damian.

The enamel plaques on the circular band, the panel depicting Christ Pantokrator, and the picture of Emperor Michael were all affixed to the crown using different techniques.

The enamel pictures that become outdated were removed, since either represented earlier historical figures or were not appropriate for the Hungarian queen according to court protocol.

[13] This view is confirmed by the fact that Grand Prince Géza is depicted on the corona gracea without a crown, although carrying a royal sceptre.

They may have decorated a reliquary box or a portable altar given to István I by the pope, or possibly the treasure binding of a book.

The picture of the apostles (Peter, Paul, James, John, Andrew, Philip, Bartholomew, Thomas), however, based on their style, cannot be dated to around 1000.

There are twelve pearls on the central panel and a total of seventy-two altogether on the corona latina, symbolising the number of Christ's disciples (Acts 10.1).

Éva Kovács and Zsuzsa Lovag suggested that the corona latina was originally a large Byzantine liturgical asterisk from a Greek monastery in Hungary.

Before Queen Isabella handed over the regalia to Ferdinand in 1551, she broke the cross off the crown’s peak for her son, John Sigismund.

[This quote needs a citation] Later, the cross became the property of Sigismund Bathory who, persuaded by his confessor, bestowed it on Emperor Rudolf II.

This was reported by an Italian envoy in Prague who also told the Isabella-John Sigismund story.” She also notes that “Several small fragments of the True Cross were in possession of the Arpad dynasty.

Éva Kovács further notes in this regard the early use of the patriarchal or double-barred cross and crown in the ancient Hungarian royal coat of arms.

On the seals of Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor, and Rudolph III of Burgundy, the rulers are holding identically shaped sceptres.

Later, the crown was housed in one of three locations: Visegrád (in Pest county); Pozsony (present-day Bratislava, Slovakia); or Buda.

Lajos Kossuth took the crown and the coronation jewels with him after the collapse of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and buried them in a wooden box in a willow forest, near Orsova in Transylvania (today Orşova, Romania).

After undergoing extensive historical research to verify the crown as genuine, it was returned to the people of Hungary by order of U.S. President Jimmy Carter on 6 January 1978.

The very large coronation mantle remains in a glass inert gas vault at the National Museum due to its delicate, faint condition.

Unlike the crown and accompanying insignia, the originally red coloured mantle is considered to date back to Stephen I, and was made circa 1030.

Old records describe the robe as handiwork of the queen and her sisters and the mantle's middle back bears the king's only known portrait (which shows his crown was not the currently existing one).

It contains a solid rock crystal ball decorated with engraved lions, a rare product of the 10th-century Fatimid caliphate.

[24] A lance claimed to have belonged to King Stephen I, and seen in the Mantle portrait, was reportedly obtained by the Holy Roman Emperor circa 1100.