Takeminakata

[20] Some of the war banners used by Sengoku daimyō Takeda Shingen (a devotee of the god) for instance contain the inscription Suwa Nangū Hosshō Kamishimo / Jōge Daimyōjin (諏訪南宮法性上下大明神 / 諏方南宮法性上下大明神).

[24] The term has also been interpreted to come from the medieval belief that the Suwa deity was the guardian of the south side of the imperial palace[25] or the Shinto-Buddhist concept that the god is an enlightened being who manifested in our world, which in Buddhist cosmology is the southern continent of Jambudvīpa.

[26] Hosshō, meanwhile, is believed to refer to the concept of the dharmakāya (法性身, hosshōshin), the formless, transcendent ultimate truth that is the source of all buddhas, which are its physical manifestations (nirmāṇakāya).

[b][37]Although it was formerly thought that the Ekotoba's compiler, Suwa (Kosaka) Enchū (1295-1364, a member of a cadet branch of the Suwa clan based in Kyoto) was responsible for excising Takeminakata's defeat out of this retelling in order to portray the deity in a more positive light, [35] Ryōtarō Maeda (2020) put forward the alternative explanation that Enchū may have made use from an anthology of excerpts or florilegium that happened to omit the relevant passage.

Records indicate that during the medieval period, the Kuji Hongi was used by the Department of Divinities or Jingi-kan (in which many Urabe clan members occupied posts) as a go-to source for inquiries regarding the histories of various shrines across the country.

A local legend in Shimoina District (located south of Suwa) for instance claims that Takemikazuchi caught up with the fleeing Takeminakata in the modern village of Toyooka, where they agreed to an armistice and left imprints of their hands on a rock as a sign of their agreement.

[67][68][69] The story relates that Ganigawara, a horse breeder who wielded great authority in the region, held Moriya in contempt for surrendering to Takeminakata and had messengers publicly harass him by calling him a coward.

Mortally wounded by an arrow in the ensuing battle, Ganigawara begs forgiveness from Moriya and entrusts his youngest daughter to Takeminakata, who gives her in marriage to the god Taokihooi-no-Mikoto (手置帆負命) a.k.a.

[73][74] In another legend, a god named Takei-Ōtomonushi (武居大伴主神 or 武居大友主神) swore allegiance to Takeminakata and became the ancestor of a line of priests in the Lower Shrine known as the Takeihōri (武居祝).

[g]Although most sources (such as the Ekotoba above) identify the boy with the semi-legendary priest Arikazu, who is said to have lived in the 9th century (early Heian period) during the reign of Emperor Kanmu (781-806) or his immediate successors Heizei (806-809) or Saga (809-823),[80][81][82][83] two genealogical lists - of disputed historical reliability[84][85] - instead identify the first priest with an individual named Otoei (乙頴) or Kumako (神子 or 熊古), a son of Mase-gimi (麻背君) or Iotari (五百足), head of the Kanasashi clan and kuni no miyatsuko of Shinano during the late 6th century.

A short text attached to a late 15th century copy of an ordinance regulating the Upper Shrine's ritual purity taboos (物忌み monoimi) originally enforced in 1238 and revised in 1317, the Suwa Kamisha monoimi no rei no koto (諏訪上社物忌令之事),[93] relates that 'Takeminakata Myōjin' (武御名方明神) was originally the ruler of a certain Indian kingdom called 'Hadai' (波堤国 Hadai-koku)[k] who survived an insurrection instigated by a rebel named 'Moriya' (守屋 or 守洩) during the king's absence while the latter was out hunting deer.

[112][113] He promises that whoever sets foot at Misayama will not fall into the lower, evil realms of existence (悪趣 akushu); conversely, the god condemns and disowns whoever defiles the hunting grounds by cutting down its trees or digging out the soil.

[p][122]After defeating this frog, Suwa Myōjin then blocked the way to its dwelling - a hole leading to the underwater palace of the dragon god of the sea, the Ryūgū-jō - with a rock and sat on it.

[128]) The frog god itself has been interpreted either as representing the native deities Mishaguji and/or Moriya, with its defeat symbolizing the victory of the cult of Suwa Myōjin over the indigenous belief system,[129][130] or as a symbol of the Buddhist concept of the three poisons (ignorance, greed, and hatred), which Suwa Myōjin, as an incarnation of the bodhisattva Samantabhadra, his esoteric aspect Vajrasattva and the Wisdom King Trailokyavijaya (interpreted as a manifestation of Vajrasattva), is said to destroy.

[131][132] Thus, the deity of Suwa is claimed to be one of the very few kami in Japan who do not leave their shrines during the month of Kannazuki, when most gods are thought to gather at Izumo and thus are absent from most of the country.

[133] A variant of this story transposes the setting from Izumo to the Imperial Palace in Kyoto; in this version, the various kami are said to travel to the ancient capital every New Year's Day to greet the emperor.

[142][143] Conversely, the omiwatari's failure to appear at all (明海 ake no umi) or the cracks forming in an unusual way were held to be a sign of bad luck for the year.

During the medieval period, legends claiming Suwa Myōjin to have appeared and provided assistance to eminent figures such as Empress Jingū[148] or the general Sakanoue no Tamuramaro[149][150][151] during their respective military campaigns circulated.

The Taiheiki recounts a story where a five-colored cloud resembling a serpent (a manifestation of the god) rose up from Lake Suwa and spread away westward to assist the Japanese army against the Mongols.

In the twenty-one shrines of Yoshino the brocade-curtained mirrors moved, the swords of the Temple-treasury put on a sharp edge, and all the shoes offered to the god turned towards the west.

[157] Pre-modern authors such as Motoori Norinaga tended to explain Takeminakata's absence outside of the Kojiki and the Kuji Hongi by conflating the god with certain obscure deities found in other sources thought to share certain similar characteristics (e.g.

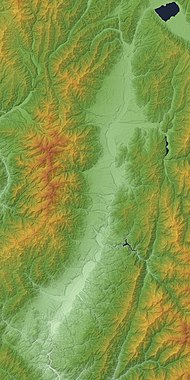

While one theory places this event during the end of the Jōmon period, thus portraying the new arrivals as agrarian Yayoi tribes who came into conflict with indigenous Jōmon hunter-gatherers,[167][168] others instead propose this conflict to have taken place during the late Kofun period (late 6th-early 7th century), when keyhole-shaped burial mounds containing equestrian gear as grave goods - up to this point found mainly in the Shimoina region southwest of Suwa - begin to appear in the Lake Suwa area, replacing the kind of burial that had been common in the region since the early 5th century.

Indeed, the Yamato polity showed strong interest to Shinano because of its suitability as a place for grazing and breeding horses and considered it a strategic base for conquering the eastern regions.

[175] In conjunction with this hypothesis, it is pointed out that in the Nobushige Gejō (believed to be the earliest attestation of this myth), the Suwa deity is said to have descended from heaven bringing with him bells, a mirror, a saddle and a bridle.

[180] Aoki (2012) theorizes that the myth developed somewhere during the late Heian and early Kamakura periods, when the deity of Suwa came to be venerated as a warrior god, and cautions against uncritical application of this story to known archaeological data.

Regarding her parentage for instance, the lore of Kawaai Shrine (川会神社) in Kitaazumi District identifies Yasakatome as the daughter of Watatsumi, god of the sea,[197] which has been seen as hinting to a connection between the goddess and the seafaring Azumi clan (安曇氏).

[198] Another claim originating from sources dating from the Edo period is that Yasakatome was the daughter of Ame-no-yasakahiko (天八坂彦命), a god recorded in the Kuji Hongi as one of the companions of Nigihayahi-no-Mikoto when the latter came down from heaven.

[229] During the medieval period, Buddhist temples and other edifices were erected on the precincts of both shrines, including a stone pagoda called the Tettō (鉄塔 "iron tower") - symbolizing the legendary iron tower in India where, according to Shingon tradition, Nagarjuna was said to have received esoteric teachings from Vajrasattva (who is sometimes identified with Samantabhadra) - and a sanctuary to Samantabhadra (普賢堂 Fugendō), both of which served at the time as the Kamisha's main objects of worship.

[232] Another festival, the Ontōsai (御頭祭) or the Tori no matsuri (酉の祭, so called because it was formerly held on the Day of the Rooster) currently held every April 15, feature the offering of seventy-five stuffed deer heads (a substitute for freshly cut heads of deer used in the past), as well as the consumption of venison and other game such as wild boar or rabbit, various kinds of seafood and other foodstuffs by the priests and other participants in a ritual banquet.

[205] These sacred licenses and chopsticks were distributed to the public both by the priests of the Kamisha as well as wandering preachers associated with the shrine known as oshi (御師), who preached the tale of Suwa Myōjin as Kōga Saburō as well as other stories concerning the god and his benefits.