Orange (fruit)

More recently, artists such as Vincent van Gogh, John Sloan, and Henri Matisse included oranges in their paintings.

[3] The orange contains a number of distinct carpels (segments or pigs, botanically the fruits) inside, typically about ten, each delimited by a membrane and containing many juice-filled vesicles and usually a few pips.

[4][5][6] The fruit is a hesperidium, a modified berry; it is covered by a rind formed by a rugged thickening of the ovary wall.

[15][16] Based on genomic analysis, the relative proportions of the ancestral species in the sweet orange are approximately 42% pomelo and 58% mandarin.

[17] All varieties of the sweet orange descend from this prototype cross, differing only by mutations selected for during agricultural propagation.

[19] In Europe, the Moors introduced citrus fruits including the bitter orange, lemon, and lime to Al-Andalus in the Iberian Peninsula during the Arab Agricultural Revolution.

[20] Large-scale cultivation started in the 10th century, as evidenced by complex irrigation techniques specifically adapted to support orange orchards.

[11] Louis XIV of France had a great love of orange trees and built the grandest of all royal Orangeries at the Palace of Versailles.

[22] At Versailles, potted orange trees in solid silver tubs were placed throughout the rooms of the palace, while the Orangerie allowed year-round cultivation of the fruit to supply the court.

[6] Subsequent expeditions in the mid-1500s brought sweet oranges to South America and Mexico, and to Florida in 1565, when Pedro Menéndez de Avilés founded St Augustine.

[11] Archibald Menzies, the botanist on the Vancouver Expedition, collected orange seeds in South Africa, raised the seedlings on board, and gave them to several Hawaiian chiefs in 1792.

The sweet orange came to be grown across the Hawaiian Islands, but its cultivation stopped after the arrival of the Mediterranean fruit fly in the early 1900s.

The Sanskrit word reached European languages through Persian نارنگ (nārang) and its Arabic derivative نارنج (nāranj).

[25] In several languages, the initial n present in earlier forms of the word dropped off because it may have been mistaken as part of an indefinite article ending in an n sound.

Around 1870, he provided trees to S. B. Parsons, a Long Island nurseryman, who in turn sold them to E. H. Hart of Federal Point, Florida.

They also are called "sweet" oranges in the United States, with similar names in other countries: douce in France, sucrena in Spain, dolce or maltese in Italy, meski in North Africa and the Near East (where they are especially popular), succari in Egypt, and lima in Brazil.

They remain profitable in areas of local consumption, but rapid spoilage renders them unsuitable for export to major population centres of Europe, Asia, or the United States.

A common process is to spray the trees with water so as to cover them with a thin layer of ice, insulating them even if air temperatures drop far lower.

[49] Commercially grown orange trees are propagated asexually by grafting a mature cultivar onto a suitable seedling rootstock to ensure the same yield, identical fruit characteristics, and resistance to diseases throughout the years.

The scion is what determines the variety of orange, while the rootstock makes the tree resistant to pests and diseases and adaptable to specific soil and climatic conditions.

In the United States, laws forbid harvesting immature fruit for human consumption in Texas, Arizona, California and Florida.

[55] Oranges are non-climacteric fruits and cannot ripen internally in response to ethylene gas after harvesting, though they will de-green externally.

[58] The first major pest that attacked orange trees in the United States was the cottony cushion scale (Icerya purchasi), imported from Australia to California in 1868.

He brought back with him specimens of an Australian ladybird, Novius cardinalis (the Vedalia beetle), and within a decade the pest was controlled.

[41] The orange dog caterpillar of the giant swallowtail butterfly, Papilio cresphontes, is a pest of citrus plantations in North America, where it eats new foliage and can defoliate young trees.

[61] As from 2009, 0.87% of the trees in Brazil's main orange growing areas (São Paulo and Minas Gerais) showed symptoms of greening, an increase of 49% over 2008.

[60] Foliar insecticides reduce psyllid populations for a short time, but also suppress beneficial predatory ladybird beetles.

Soil application of aldicarb provided limited control of Asian citrus psyllid, while drenches of imidacloprid to young trees were effective for two months or more.

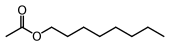

The oil consists of approximately 90% D-limonene, a solvent used in household chemicals such as wood conditioners for furniture and—along with other citrus oils—detergents and hand cleansers.

She writes that Zhao Lingrang's fan painting Yellow Oranges and Green Tangerines pays attention not to the fruit's colour but the shape of the fruit-laden trees, and that Su Shi's poem on the same subject runs "You must remember, / the best scenery of the year, / Is exactly now, / when oranges turn yellow and tangerines green.