Sharia

Over time with the necessities brought by sociological changes, on the basis of interpretative studies legal schools have emerged, reflecting the preferences of particular societies and governments, as well as Islamic scholars or imams on theoretical and practical applications of laws and regulations.

[29] A related term al-qānūn al-islāmī (القانون الإسلامي, Islamic law), which was borrowed from European usage in the late 19th century, is used in the Muslim world to refer to a legal system in the context of a modern state.

[56][5][57] It continued some aspects of pre-Islamic laws and customs of the lands that fell under Muslim rule in the aftermath of the early conquests and modified others, aiming to meet the practical need of establishing Islamic norms of behavior and adjudicating disputes arising in the community.

[6][11] Classical Islamic jurisprudence refers how to elaborate and interpret religious sources that are considered reliable within the framework of "procedural principles" within its context such as linguistic and "rhetorical tools" to derive judgments for new situations by taking into account certain purposes and mesalih.

[6] The theory of Twelver Shia jurisprudence parallels that of Sunni schools with some differences, such as recognition of reason (ʿaql) as a source of law in place of qiyas and extension of the notion of sunnah to include traditions of the imams.

[108] They were first clearly articulated by al-Ghazali (d. 1111), who argued that Maqāṣid and maslaha was God's general purpose in revealing the divine law, and that its specific aim was preservation of five essentials of human well-being: religion, life, intellect, offspring, and property.

[112] While the latter view was held by a minority of classical jurists, in modern times it came to be championed in different forms by prominent scholars who sought to adapt Islamic law to changing social conditions by drawing on the intellectual heritage of traditional jurisprudence.

[15] The classical process of ijtihad combined these generally recognized principles with other methods, which were not adopted by all legal schools, such as istihsan (juristic preference), istislah (consideration of public interest) and istishab (presumption of continuity).

[citation needed] A special religious decision, which is "specific to" a person, group, institution, event, situation, belief and practice in different areas of life, and usually includes the approval/disapproval of a judgment, is called fatwa.

[5][149] Mustafa Öztürk points out some another developments in the Islamic creed, leading changes in ahkam such as determining the conditions of takfir according to theologians; First Muslims believed that God lived in the sky as Ahmad Ibn Hanbal says: "Whoever says that Allah is everywhere is a heretic, an infidel, should be invited to repent, but if he does not, be killed."

[172] Students specializing in law would complete a curriculum consisting of preparatory studies, the doctrines of a particular madhhab, and training in legal disputation, and finally write a dissertation, which earned them a license to teach and issue fatwas.

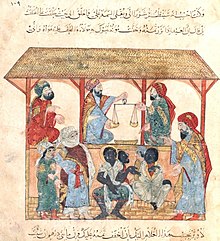

The ulema (religious scholars) were involved in management of communal affairs and acted as representatives of the Muslim population vis-à-vis the ruling dynasties, who before the modern era had limited capacity for direct governance.

This conception was reinforced by the historical practice of Sharia courts, where peasants "almost always" won cases against oppressive landowners, and non-Muslims often prevailed in disputes against Muslims, including such powerful figures as the governor of their province.

In the traditional Islamic context, a concise text like Al-Hidayah would be used as a basis for classroom commentary by a professor, and the doctrines thus learned would be mediated in court by judicial discretion, consideration of local customs and availability of different legal opinions that could fit the facts of the case.

Like the British in India, colonial administrations typically sought to obtain precise and authoritative information about indigenous laws, which prompted them to prefer classical Islamic legal texts over local judicial practice.

This, together with their conception of Islamic law as a collection of inflexible rules, led to an emphasis on traditionalist forms of Sharia that were not rigorously applied in the pre-colonial period and served as a formative influence on the modern identity politics of the Muslim world.

For example, the 1979 reform of Egyptian family law, promulgated by Anwar Sadat through presidential decree, provoked an outcry and was annulled in 1985 by the supreme court on procedural grounds, to be later replaced by a compromise version.

[5] In practice, Islamization campaigns have focused on a few highly visible issues associated with the conservative Muslim identity, particularly women's hijab and the hudud criminal punishments (whipping, stoning and amputation) prescribed for certain crimes.

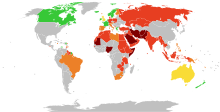

[209] Several countries, including Iran, Pakistan, Sudan, and some Nigerian states have incorporated hudud rules into their criminal justice systems, which, however, retained fundamental influences of earlier Westernizing reforms.

[5][26] In practice, these changes were largely symbolic, and aside from some cases brought to trial to demonstrate that the new rules were being enforced, hudud punishments tended to fall into disuse, sometimes to be revived depending on the local political climate.

In mixed legal systems, Sharia rules are allowed to influence some national laws, which are codified and may be based on European or Indian models, and the central legislative role is played by politicians and modern jurists rather than the ulema (traditional Islamic scholars).

[337] Representatives of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation have petitioned the United Nations to condemn "defamation of religions" because "Unrestricted and disrespectful freedom of opinion creates hatred and is contrary to the spirit of peaceful dialogue".

[371] Public attitudes toward homosexuality in the Muslim world turned more negative starting from the 19th century through the gradual spread of Islamic fundamentalist movements such as Salafism and Wahhabism,[372][373][374] and under the influence of sexual notions prevalent in Europe at that time.

[378][379] In recent decades, prejudice against LGBT individuals in the Muslim world has been exacerbated by increasingly conservative attitudes and the rise of Islamist movements, resulting in Sharia-based penalties enacted in several countries.

[379] The death penalty for homosexual acts is currently a legal punishment in Brunei, Iran, Mauritania, some northern states in Nigeria, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, parts of Somalia, and Yemen, all of which have Sharia-based criminal laws.

[Quran 4:11][79] Jonathan A.C. Brown says: The vast majority of the ulama across the Sunni schools of law inherited the Prophet's unease over domestic violence and placed further restrictions on the evident meaning of the 'Wife Beating Verse'.

Darimi, a teacher of both Tirmidhi and Muslim bin Hajjaj as well as a leading early scholar in Iran, collected all the Hadiths showing Muhammad's disapproval of beating in a chapter entitled 'The Prohibition on Striking Women'.

A thirteenth-century scholar from Granada, Ibn Faras, notes that one camp of ulama had staked out a stance forbidding striking a wife altogether, declaring it contrary to the Prophet's example and denying the authenticity of any Hadiths that seemed to permit beating.

[390][391] According to some interpretations, Sharia condones certain forms of domestic violence against women, when a husband suspects nushuz (disobedience, disloyalty, rebellion, ill conduct) in his wife only after admonishing and staying away from the bed does not work.

[426][427] According to Bernard Lewis, "[a]t no time did the classical jurists offer any approval or legitimacy to what we nowadays call terrorism"[428] and the terrorist practice of suicide bombing "has no justification in terms of Islamic theology, law or tradition".