Symmetric difference

The symmetric difference of the sets A and B is commonly denoted by

It can be viewed as a form of addition modulo 2.

The power set of any set becomes an abelian group under the operation of symmetric difference, with the empty set as the neutral element of the group and every element in this group being its own inverse.

The symmetric difference is equivalent to the union of both relative complements, that is:[1] The symmetric difference can also be expressed using the XOR operation ⊕ on the predicates describing the two sets in set-builder notation: The same fact can be stated as the indicator function (denoted here by

) of the symmetric difference, being the XOR (or addition mod 2) of the indicator functions of its two arguments:

The symmetric difference can also be expressed as the union of the two sets, minus their intersection: In particular,

; the equality in this non-strict inclusion occurs if and only if

Consequently, assuming intersection and symmetric difference as primitive operations, the union of two sets can be well defined in terms of symmetric difference by the right-hand side of the equality The symmetric difference is commutative and associative: The empty set is neutral, and every set is its own inverse: Thus, the power set of any set X becomes an abelian group under the symmetric difference operation.

(More generally, any field of sets forms a group with the symmetric difference as operation.)

Sometimes the Boolean group is actually defined as the symmetric difference operation on a set.

[4] In the case where X has only two elements, the group thus obtained is the Klein four-group.

Equivalently, a Boolean group is an elementary abelian 2-group.

Consequently, the group induced by the symmetric difference is in fact a vector space over the field with 2 elements Z2.

If X is finite, then the singletons form a basis of this vector space, and its dimension is therefore equal to the number of elements of X.

From the property of the inverses in a Boolean group, it follows that the symmetric difference of two repeated symmetric differences is equivalent to the repeated symmetric difference of the join of the two multisets, where for each double set both can be removed.

In particular: This implies triangle inequality:[5] the symmetric difference of A and C is contained in the union of the symmetric difference of A and B and that of B and C. Intersection distributes over symmetric difference: and this shows that the power set of X becomes a ring, with symmetric difference as addition and intersection as multiplication.

Further properties of the symmetric difference include: The symmetric difference can be defined in any Boolean algebra, by writing This operation has the same properties as the symmetric difference of sets.

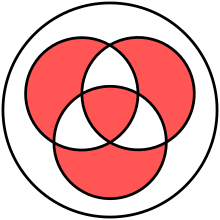

The symmetric difference of a collection of sets contains just elements which are in an odd number of the sets in the collection:

Evidently, this is well-defined only when each element of the union

is contributed by a finite number of elements of

, given solely in terms of intersections of elements of

As long as there is a notion of "how big" a set is, the symmetric difference between two sets can be considered a measure of how "far apart" they are.

First consider a finite set S and the counting measure on subsets given by their size.

Now consider two subsets of S and set their distance apart as the size of their symmetric difference.

If μ is a σ-finite measure defined on a σ-algebra Σ, the function is a pseudometric on Σ. dμ becomes a metric if Σ is considered modulo the equivalence relation X ~ Y if and only if

One may define an equivalence relation on measurable sets by letting

" is a partial order on the family of subsets of

The Hausdorff distance and the (area of the) symmetric difference are both pseudo-metrics on the set of measurable geometric shapes.

When the Hausdorff distance between them becomes smaller, the area of the symmetric difference between them becomes larger, and vice versa.

By continuing these sequences in both directions, it is possible to get two sequences such that the Hausdorff distance between them converges to 0 and the symmetric distance between them diverges, or vice versa.