Sympatry

Such speciation may be a product of reproductive isolation – which prevents hybrid offspring from being viable or able to reproduce, thereby reducing gene flow – that results in genetic divergence.

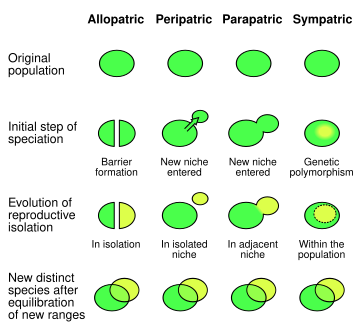

[3] Allopatric populations isolated from one another by geographical factors (e.g., mountain ranges or bodies of water) may experience genetic—and, ultimately, phenotypic—changes in response to their varying environments.

[citation needed] The lack of geographic isolation as a definitive barrier between sympatric species has yielded controversy among ecologists, biologists, botanists, and zoologists regarding the validity of the term.

Others question the ability of sympatry to result in complete speciation: until recently, many researchers considered it nonexistent, doubting that selection alone could create disparate, but not geographically separated, species.

In 2003, biologist Karen McCoy suggested that sympatry can act as a mode of speciation only when "the probability of mating between two individuals depend[s] [solely] on their genotypes, [and the genes are] dispersed throughout the range of the population during the period of reproduction".

[4] In essence, sympatric speciation does require very strong forces of natural selection to be acting on heritable traits, as there is no geographic isolation to aid in the splitting process.

As speciation progresses, isolating mechanisms – such as gametic incompatibility that renders fertilization of the egg impossible – are selected for in order to increase the reproductive divide between the two populations.

It is also apparent in the differences in levels of prezygotic isolation (by factors that prevent formation of a viable zygote) in both sympatric and allopatric populations.

In sympatry, reinforcement increases species discrimination and sexual adaptation in order to avoid maladaptive hybridization and encourage speciation.

However, Coyne and Orr found equal levels of postzygotic isolation among sympatric and allopatric species pairs in closely related Drosophila.

In the North Pacific, three whale populations – called "transient", "resident", and "offshore" – demonstrate partial sympatry, crossing paths with relative frequency.

[10] The parasitic great spotted cuckoo (Clamator glandarius) and its magpie host, both native to Southern Europe, are completely sympatric species.

For example, great spotted cuckoos and their magpie hosts in Hoya de Gaudix, southern Spain, have lived in sympatry since the early 1960s, while species in other locations have more recently become sympatric.

This active isolation of individual populations helps maintain the genetic purity of the fungal colony, and this mechanism may lead to sympatric speciation within a shared habitat.