Host–parasite coevolution

A possible result is a geographic mosaic in a parasitised population, as both host and parasite adapt to environmental conditions that vary in space and time.

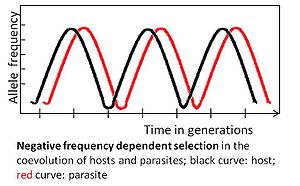

[1] The dynamics of these interactions are summarized in the Red Queen hypothesis, namely that both host and parasite have to change continuously to keep up with each other's adaptations.

[2] Host–parasite coevolution is ubiquitous and of potential importance to all living organisms, including humans, domesticated animals and crops.

Better understanding of coevolutionary adaptations between parasite attack strategies and host immune systems may assist in the development of novel medications and vaccines.

In turn, a rare host genotype may then be favored by selection, its frequency will increase and eventually it becomes common.

At the same time, the mutation confers resistance to malaria, caused by Plasmodium parasites, which are passed off in red blood cells after transmission to humans by mosquitoes.

[7][8] If an allele provides a fitness benefit, its frequency increases within a population – selection is directional or positive.

[1] This mode of selection is likely to occur in interactions between unicellular organisms and viruses due to large population sizes, short generation times, often haploid genomes and horizontal gene transfer, which increase the probability of beneficial mutations arising and spreading through populations.

[3] John N. Thompson's geographic mosaic theory of coevolution hypothesizes spatially divergent coevolutionary selection, producing genetic differentiation across populations.

[9] The model assumes three elements that jointly fuel coevolution:[10][11][12] 1) a selection mosaic among populations 2) coevolutionary hotspots 3) geographic mixing of traits These processes have been intensively studied in a plant, Plantago lanceolata, and its parasite the powdery mildew Podosphaera plantaginis in Åland in south-western Finland.

The mildew's success at overwintering, and the intensity of host-pathogen encounters in summer, strongly vary geographically.

[14][9] The Red Queen hypothesis states that both host and parasite have to change continuously to keep up with each other's adaptations, like the description in Lewis Carroll's fiction.

[15][16] The New Zealand freshwater snail Potamopyrgus antipodarum and its different trematode parasites represent a rather special model system.

This trade-off is supported by coevolutionary experiments, which revealed the decrease of virulence, a constant transmission potential and an increase in the host's lifespan over a period of time.

The bacterium may prevent injection by altering the relevant binding site, e.g. in response to point mutations or deletion of the receptor.

[20] The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis have become established as a model system for studying host–parasite coevolution.

The study demonstrated that parasites were on average most infective with their contemporary hosts,[22] consistent with negative frequency-dependent selection.

[23] Escherichia coli, a Gram-negative proteobacterium, is a common model in biological research, for which comprehensive data on various aspects of its life-history is available.