Synchronous condenser

The condenser’s installation and operation are identical to large electric motors and generators (some generators are actually designed to be able to operate as synchronous condensers with the prime mover disconnected[2]).

Increasing the device's field excitation results in its furnishing reactive power (measured in units of var) to the system.

Synchronous condensers are an alternative to capacitor banks and static VAR compensators for power-factor correction in power grids.

[3] One advantage is that the amount of reactive power from a synchronous condenser can be continuously adjusted.

[1] Additionally, synchronous condensers are more tolerant of power fluctuations and severe drops in voltage.

[3] However, synchronous machines have higher energy losses than static capacitor banks.

There is no explosion hazard as long as the hydrogen concentration is maintained above 70%, typically above 91%.

[4] A syncon can be 8 metres long and 5 meters tall, weighing 170 tonnes.

The inertial response of the machine and its inductance can help stabilize a power system during rapid fluctuations of loads such as those created by short circuits or electric arc furnaces.

[7][3] A rotating coil [8] in a magnetic field tends to produce a sine-wave voltage.

Note that mechanical torque (produced by a motor, required by a generator) corresponds only to the real power.

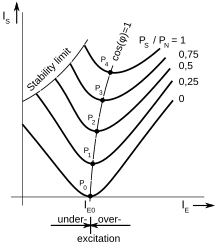

As the mechanical load on a synchronous motor increases, the stator current

When over-excited, the motor runs with leading power factor (and supplies vars to the grid) and when under-excited with lagging power factor (and absorbs vars from the grid).

As in a synchronous motor, the stator of the machine is connected to a three-phase supply of voltage

(assumed to be constant), and this creates a rotating magnetic field within the machine.

In normal operation the rotor magnet follows the stator field at synchronous speed.

If the machine is considered to be ideal, with no mechanical, magnetic, or electrical losses, its equivalent circuit will be an AC generator in series with the winding inductance

Both transformers and induction motors draw lagging (magnetising) currents from the line.

This improves the plant power factor and reduces the reactive current required from the grid.

A synchronous condenser provides stepless automatic power-factor correction with the ability to produce up to 150% additional vars.

They will not produce excessive voltage levels and are not susceptible to electrical resonances.

Because of the rotating inertia of the synchronous condenser, it can provide limited voltage support during very short power drops.

Rotating synchronous condensers were introduced in 1930s[2] and were common in 1950s, but due to high costs were eventually displaced in new installations by the static var compensators (SVCs).

The reactive power produced by a capacitor bank is in direct proportion to the square of its terminal voltage, and if the system voltage decreases, the capacitors produce less reactive power, when it is most needed,[2] while if the system voltage increases the capacitors produce more reactive power, which exacerbates the problem.

In contrast, with a constant field, a synchronous condenser naturally supplies more reactive power to a low voltage and absorbs more reactive power from a high voltage, plus the field can be controlled.

A PLC based controller with PF controller and regulator will allow the system to be set to meet a given power factor or can be set to produce a specified amount of reactive power.

[9] In addition to purpose-built units, existing steam or combustion turbines can be retrofit for use as a syncon.

Using purely electric startup methods, the syncon relies on the starter motor to provide an initial startup, and the generator or auxiliary motor provide the system with the necessary rotational inertia to produce reactive power.

With the SSS clutch retrofit, the existing turbine setup is largely reused.

The generator thus uses grid energy to keep spinning, to provide leading or lagging reactive power as needed.