Syrinx (bird anatomy)

[5] Within the avian stem lineage, the transition from a larynx-based sound source to a tracheobronchial syrinx occurred within Dinosauria, at or before the origin of Aves about 66-68 million years ago.

[7] Before this discovery, syringeal components were thought to enter the fossil record infrequently, making it difficult to determine when the shift in vocal organs occurred.

[8] An intact specimen from the late Cretaceous, however, highlights the fossilization potential of the ancestral structure and may indicate that the syrinx is a late-arising feature in avian evolution.

[12] In continuous breathers, such as birds and mammals, the trachea is exposed to fluctuations of wall shear stress during inspiration and expiration.

Distinct airway geometries in Mammalia and Archosauria may have also impacted syrinx evolution: the bronchi in crocodiles and humans, for example, diverge at different angles.

Because sound is produced through the interaction of airflow and the self-oscillation of membranes within the trachea, a mechanism is necessary to abduct structures from the airway to allow for non-vocal respiration.

[6] Therefore, the two pairs of extrinsic muscles present in the ancestral syrinx were likely selected to ensure that the airway did not collapse during non-vocal respiration.

[15] Further fossil data and taxonomical comparisons will be necessary to determine whether structural modifications of the syrinx unrelated to sound, such as respiratory support during continuous breathing or in flight, were exapted in the development of a vocal organ.

While a need for structural support may have given rise to an organ at the tracheobronchial juncture, selection for vocal performance likely played a role in syrinx evolution.

Riede et al. (2019) argue that because birds with deactivated syringeal muscles can breathe without difficulty within a lab setting, vocal pressures must have been central to the morphological shift.

This is a critical distinction between the structures, as the length of the air column above and below a sound source affects the way energy is conveyed from airflow to oscillating tissue.

Thus, acoustic theory predicts that to maximize energy transfer, birds must develop an appropriate length-frequency combination that produces inertance at the input of the trachea.

Riede et al. therefore conclude that the evolution of a simple syrinx may be tied to specific combinations of vocal fold morphology and body size.

Before the origin of Aves and during the late Jurassic period, theropod-lineage dinosaurs underwent stature miniaturization and rapid diversification.

[17] It is possible that during these changes, certain co[6] mbinations of body-size dependent vocal tract length and sound frequencies favored the evolution of the novel syrinx.

[19] With a longer trachea, the avian vocal system shifted to a range in which an overlap between fundamental frequency and first tracheal resonance was possible.

At this point in avian evolution, it may have become advantageous to move the vocal structure upstream to the syringeal position, near the tracheobronchial juncture.

Specifically, long necks facilitate underwater predation, evident in the extant genera Cygnus (swans) and Cormorant (shags).

[10] With bolstered vocal efficiency due to longer necks, the syrinx may have been retained in Aves by sexual selective forces.

[22] While the specific acoustic advantage of the ancestral syrinx remains speculative, it is evident from modern avian diversification that sexual selection often drives vocal evolution.

[24] Birds that exhibit sexual dimorphism in the syrinx can present itself at around 10 days in Pekin ducks (Anas platyrhynchos domestica).

[25] Females have a louder call because the space inside their bulla is not lined with a lot of fat or connective tissue, and the thinner tympaniform membrane takes less effort to vibrate.

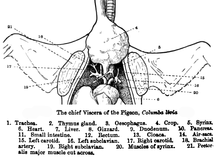

1: last free cartilaginous tracheal ring , 2: Trachea 3: first group of syringeal rings, 4: pessulus , 5: membrana tympaniformis lateralis, 6: membrana tympaniformis medialis, 7: second group of syringeal rings, 8: main bronchus , 9: bronchial cartilage