T. W. Robertson

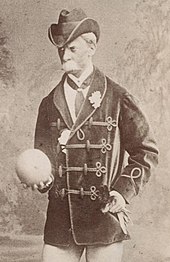

Thomas William Robertson (9 January 1829 – 3 February 1871) was an English dramatist and stage director known for his development of naturalism in British theatre.

Their naturalistic style and treatment of contemporary social issues was in strong contrast to the melodramas and exaggerated theatricality to which the public had been accustomed, and Robertson's plays were box-office and critical successes.

Among later theatrical figures influenced by Robertson's Prince of Wales's plays and productions were W. S. Gilbert, Arthur Wing Pinero, Bernard Shaw and Harley Granville-Barker.

[1] He came from a long-established theatrical family, active on the English stage since the early 18th century,[2] and was the eldest son of William Shaftoe Robertson and his wife, Margharetta Elisabetta (née Marinus), a Danish-born actress.

[3] Many of Robertson's large family of siblings went on the stage, including his brothers Frederick and Edward, and his sisters Fanny, Elizabeth and Margaret, the last subsequently famous as Madge Kendal.

When he was about 15 his schooling ceased and he rejoined the company full-time,[7] not only as an actor, but also, according to his biographer Michael R. Booth, "as a scene painter, songwriter, playwright, prompter, and stage-manager".

In addition to writing and adapting plays he contributed stories, essays, and verses to many magazines: dramatic criticisms to several newspapers: and ephemeral work to numerous comic journals".

[10] In 1851 Robertson had a new play presented in the West End, A Night's Adventure, a comic drama set in the time of the Jacobite rising of 1745.

[12] He worked as a prompter at the Olympic Theatre,[1] tried unsuccessfully to join the army, and travelled to Paris with a company giving a season of English plays there.

[16] Robertson's farcical sketch The Cantab, staged as an after-piece at the Strand Theatre in February 1861, attracted the attention of a Bohemian literary set, and led to his becoming a member of the Savage, Arundel and Reunion Clubs, where, in the words of his biographer Joseph Knight, "he enlarged his observation of human nature, and whence he drew some curious types".

The actor was at the height of his popularity, and although the notices paid more attention to his performance than to Robertson's writing,[18] the success of the production advanced the author's career.

His next, the comedy Ours, was first given in August 1866 at the Prince of Wales's, Liverpool, under his personal direction with a cast that included Wilton, Squire Bancroft (her future husband and partner) and John Hare.

[8] In the same year Robertson adapted Alfred de Musset's 1834 play On ne badine pas avec l'amour for his sister Madge.

[34] In late 1868 Robertson adapted Émile Augier's comedy L'Aventurière, presented at the Haymarket as Home, with Sothern in the lead role, and Ada Cavendish as Mrs Pinchbeck, in January 1869.

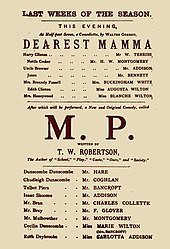

He continued to write, and 1870 saw the production of Progress (adapted from Sardou) at the Globe, The Nightingale, a drama, at the Adelphi Theatre and his final work for the Prince of Wales's – M. P.. Robertson was an early beneficiary of improved financial terms for playwrights; the practice of payment by royalties was not widespread until the 1880s, but the management of the Prince of Wales's had paid him £1 a night for Society in 1865, and by the time of this final piece his nightly fee had risen to £5.

More than a thousand people attended the funeral, including the entire company of the Prince of Wales's, led by Marie Wilton, who placed a chaplet of flowers on the coffin.

[11][39] The plays were notable for what the critic Thomas Purnell dubbed their "cup and saucer" realism, treating contemporary British subjects in settings that were recognisable, unlike the oversized acting in Victorian melodramas that were popular at the time.

[40] Shaw was mistaken in supposing everyone was delighted: some critics wrote that there was nothing in Robertson's plays but commonplace life represented without a trace of wit and sparkle, and absurdly realistic.

[41] More typical was the comment by a correspondent in The Era shortly after Robertson's death, asking who else could "successfully break, as he did, the trammels of conventionalism, and show us upon the stage living, breathing figures of flesh and blood, who walk, talk, act and think as tangible men and women really do in this work-a-day world of ours".

In a 1972 study Errol Durbach suggests that "the 'revolution' had been initiated in France years before by Scribe and Sardou, those forerunners of the bourgeois domestic theatre and the well-made play".

Dion Boucicault had been a forerunner, directing spectacular productions of his own plays, but Robertson applied the directorial precept to English domestic drama for the first time.

[45] Unlike Boucicault he did not act in his plays but applied himself exclusively to directing (or as it was called at the time "stage management")[n 7] and in that capacity he could focus on ensemble and balance.