TWA Flight 800

On July 17, 1996, at approximately 8:31 p.m. EDT, twelve minutes after takeoff, the Boeing 747-100 serving the flight exploded and crashed into the Atlantic Ocean near East Moriches, New York, United States.

Accident investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) traveled to the scene, arriving the following morning[2]: 313 amid speculation that a terrorist attack was the cause of the crash.

3 (treated as a minimum equipment list item) because of technical problems with the thrust reverser sensors during the landing of TWA 881 at JFK, before Flight 800's departure.

To continue the pressure fueling, a TWA mechanic overrode the automatic VSO by pulling the volumetric fuse and an overflow circuit breaker.

[2]: 31 TWA 800 was scheduled to depart JFK for Charles de Gaulle Airport around 7:00 p.m., but the flight’s pushback was delayed until 8:02 p.m. by a disabled piece of ground equipment and a passenger/baggage mismatch.

[15]: 4 [16][17] The last recorded radar transponder return from the airplane was recorded by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) radar site at Trevose, Pennsylvania, at 8:31:12 p.m.[2]: 3 Thirty-eight seconds later, David McClaine, the captain of Eastwind Airlines Flight 507, a Boeing 737-221 registered N221US (which had suffered a near-crash of its own a month prior)[18] reported to Boston ARTCC that he "just saw an explosion out here", adding, "we just saw an explosion up ahead of us here ... about 16,000 feet [4,900 m] or something like that, it just went down… into the water.

[19] Many witnesses in the vicinity of the crash stated that they saw or heard explosions, accompanied by a large fireball(s) over the ocean, and observed debris, some of which was burning while falling into the water.

They searched for survivors but found none,[2]: 86 making TWA 800 the second-deadliest aircraft accident in United States history at that time, only exceeded by American Airlines Flight 191.

Notable passengers included:[22] In addition, 16 students and five adult chaperones from the French Club of the Montoursville Area High School in Pennsylvania were on board.

Remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), side-scan sonar and laser line-scanning equipment were employed to search for and investigate underwater debris fields.

[2]: 71–74 Pieces of wreckage were transported by boat to shore and then by truck to leased hangar space at the former Grumman Aircraft facility in Calverton, New York for storage, examination, and reconstruction.

[39][40][41] Many grieving relatives became angry because of TWA's delayed confirmation of the passenger list,[36] conflicting information from agencies and officials[42]: 1 and mistrust of the recovery operation's priorities.

[43]: 2 Although NTSB vice chairman Robert Francis stated that all bodies were retrieved as soon as they were spotted and that wreckage was recovered only if divers believed that victims were hidden underneath,[43]: 2 many families were suspicious that investigators were not truthful or were withholding information.

[34]: 3 [44]: 4 The International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, an invited party to the NTSB investigation, criticized the undocumented removal by FBI agents of wreckage from the hangar where it was stored.

"[2]: 257 A review of recorded data from long-range and airport surveillance radars revealed multiple contacts of airplanes or objects in TWA 800's vicinity at the time of the accident.

[2]: 94 Further, review of the Islip radar data for similar summer days and nights in 1999 indicated that the 30-knot track was consistent with normal commercial fishing, recreational, and cargo-vessel traffic.

[2]: 118 Further examination of the airplane structure, seats, and other interior components found no damage typically associated with a high-energy explosion of a bomb or missile warhead ("severe pitting, cratering, petalling or hot-gas washing").

[2]: 258 The NTSB considered the possibility that the explosive residue was the result of contamination from the aircraft's use in transporting troops during the Gulf War in 1991 or its use in a dog-training explosive-detection exercise about one month before the accident.

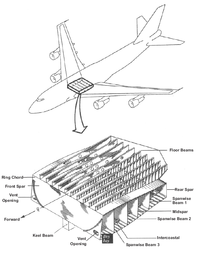

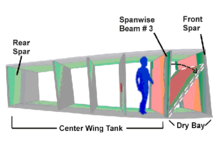

[2]: 137 To better determine whether a fuel-air vapor explosion in the CWT would generate sufficient pressure to break apart the fuel tank and lead to the destruction of the airplane, tests were conducted in July and August 1997 using a retired Air France 747 at Bruntingthorpe Airfield, England.

[2]: 109, 263 Shortly after, the left wing separated from what remained of the main fuselage, which resulted in further development of the fuel-fed fireballs as the pieces of wreckage fell to the ocean.

[2]: 95–96 Hundreds of simulations were run using various combinations of possible times the nose of TWA 800 separated (the exact time was unknown), different models of the behavior of the crippled aircraft (the aerodynamic properties of the aircraft without its nose could only be estimated), and longitudinal radar data (the recorded radar tracks of the east/west position of TWA 800 from various sites differed).

"[2]: 265 In addition, 18 witnesses reported seeing a streak of light that originated at the surface, or the horizon, which did not "appear to be consistent with the airplane's calculated flightpath and other known aspects of the accident sequence.

[2]: 290 Experiments showed that applying power to a wire leading to the fuel quantity gauge can cause the digital display to change by several hundred pounds before the circuit breaker trips.

The source of ignition energy for the explosion could not be determined with certainty, but, of the sources evaluated by the investigation, the most likely was a short circuit outside of the CWT that allowed excessive voltage to enter it through electrical wiring associated with the fuel quantity indication system.In addition to the probable cause, the NTSB found the following contributing factors to the accident:[2]: 308 During the course of its investigation, and in its final report, the NTSB issued 15 safety recommendations, mostly covering fuel tank and wiring-related issues.

[57]: 6 After the accident, former Joint Chief of Staff Thomas Moorer and former White House Press Secretary Pierre Salinger speculated that the airplane was destroyed by a missile, with a nearby U.S. Navy ship being the likely culprit.

"[59] Speculation was fueled in part by early descriptions, visuals, and eyewitness accounts of the disaster that indicated a sudden explosion and trails of fire moving in an upward direction.

[66] On July 18, 2008, the United States Secretary of Transportation Mary E. Peters visited the facility and announced a final rule designed to prevent accidents caused by fuel-tank explosions.

Among other things, the act gives NTSB, instead of the particular airline involved, responsibility for coordinating services to the families of victims of fatal aircraft accidents in the United States.

[72] The TWA Flight 800 International Memorial was dedicated in a 2-acre (8,100 m2) parcel immediately adjoining the main pavilion at Smith Point County Park in Shirley, New York, on July 14, 2002.

By 2021, the methods taught using the wreckage were determined to no longer be relevant to modern accident investigation, which by then relied heavily on new technology, including three-dimensional laser-scanning techniques.