Tacitus on Jesus

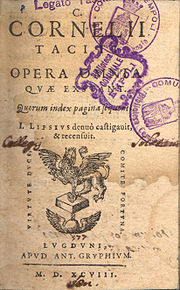

The Roman historian and senator Tacitus referred to Jesus, his execution by Pontius Pilate, and the existence of early Christians in Rome in his final work, Annals (written c. AD 116), book 15, chapter 44.

[1] The context of the passage is the six-day Great Fire of Rome that burned much of the city in AD 64 during the reign of Roman Emperor Nero.

The scholarly consensus is that Tacitus's reference to the execution of Jesus by Pontius Pilate is both authentic, and of historical value as an independent Roman source.

[11][12] Tacitus is one of the non-Christian writers of the time who mentioned Jesus and early Christianity along with Flavius Josephus, Pliny the Younger, and Suetonius.

Sed non ope humana, non largitionibus principis aut deum placamentis decedebat infamia, quin iussum incendium crederetur.

ergo abolendo rumori Nero subdidit reos et quaesitissimis poenis adfecit, quos per flagitia invisos vulgus Chrestianos appellabat.

auctor nominis eius Christus Tibero imperitante per procuratorem Pontium Pilatum supplicio adfectus erat; repressaque in praesens exitiabilis superstitio rursum erumpebat, non modo per Iudaeam, originem eius mali, sed per urbem etiam, quo cuncta undique atrocia aut pudenda confluunt celebranturque.

igitur primum correpti qui fatebantur, deinde indicio eorum multitudo ingens haud proinde in crimine incendii quam odio humani generis convicti sunt.

Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace.

Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judæa, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular.

Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.

Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car.

Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man's cruelty, that they were being destroyed.

[26] Adolf von Harnack argued that Chrestians was the original wording, and that Tacitus deliberately used Christus immediately after it to show his own superior knowledge compared to the population at large.

[51] Scholars such as Bruce Chilton, Craig Evans, Paul Eddy and Gregory Boyd agree with John Meier's statement that "Despite some feeble attempts to show that this text is a Christian interpolation in Tacitus, the passage is obviously genuine".

[17] When Tacitus wrote his account, he was the governor of the province of Asia, and as a member of the inner circle in Rome he would have known of the official position with respect to the fire and the Christians.

[17] William L. Portier has stated that the references to Christ and Christians by Tacitus, Josephus and the letters to Emperor Trajan by Pliny the Younger are consistent, which reaffirms the validity of all three accounts.

[29] Tacitus was a member of the Quindecimviri sacris faciundis, a council of priests whose duty it was to supervise foreign religious cults in Rome, which as Van Voorst points out, makes it reasonable to suppose that he would have acquired knowledge of Christian origins through his work with that body.

[10] Biblical scholar Bart D. Ehrman wrote: "Tacitus's report confirms what we know from other sources, that Jesus was executed by order of the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, sometime during Tiberius's reign.

[69] Shaw's views have received strong criticism and have generally not been accepted by the scholarly consensus:[67] Christopher P. Jones (Harvard University) answered to Shaw and refuted his arguments, noting that the Tacitus's anti-Christian stance makes it unlikely that he was using Christian sources; he also noted that the Epistle to the Romans of Paul the Apostle clearly points to the fact that there was indeed a clear and distinct Christian community in Rome in the 50s and that the persecution is also mentioned by Suetonius in The Twelve Caesars.

[72] John Granger Cook also rebuked Shaw's thesis, arguing that Chrestianus, Christianus, and Χριστιανός are not creations of the second century and that Roman officials were probably aware of the Chrestiani in the 60s.

The earliest known references to Christianity are found in Antiquities of the Jews, a 20-volume work written by the Jewish historian Titus Flavius Josephus around 93–94 AD, during the reign of emperor Domitian.

[78][79][80] Tacitus' references to Nero's persecution of Christians in the Annals were written around 115 AD,[77] a few years after Pliny's letter but also during the reign of emperor Trajan.

Another notable early author was Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, who wrote the Lives of the Twelve Caesars around 122 AD,[77] during the reign of emperor Hadrian.