Tai peoples

According to Michel Ferlus, the ethnonyms Tai/Thai (or Tay/Thay) evolved from the etymon *k(ə)ri: 'human being' through the following chain: kəri: > kəli: > kədi:/kədaj (-l- > -d- shift in tense sesquisyllables and probable diphthongization of -i: > -aj).

Michel Ferlus' work is based on some simple rules of phonetic change observable in the Sinosphere and studied for the most part by William H. Baxter (1992).

[6] In fact, Keo/ Kæw kɛːwA1 was an exonym used to refer to Tai speaking peoples, as in the epic poem of Thao Cheuang, and was only later applied to the Vietnamese.

[8] The Nung living on both sides of the Sino-Vietnamese border have their ethnonym derived from clan name Nong (儂 / 侬), whose bearers dominated what are now north Vietnam and Guangxi in the 11th century AD.

[citation needed] Another name that's shared between the Nung, the Tay, and the Zhuang living along the Sino-Vietnamese border is Tho, which literally means autochthonous.

However, this term was also applied to the Tho people, who are a separate group of indigenous speakers of Vietic languages, who have come under the influence of Tai culture.

[citation needed] James R. Chamberlain (2016) proposes that the Tai-Kadai (Kra-Dai) language family was formed as early as the 12th century BC in the middle of the Yangtze basin, coinciding roughly with the establishment of the Chu state and the beginning of the Zhou dynasty.

[9] Comparative linguistic research seems to indicate that the Tai peoples were a Proto-Tai–Kadai speaking culture of southern China and dispersed into mainland Southeast Asia.

Roger Blench (2008) demonstrates that dental evulsion, face tattooing, teeth blackening and snake cults are shared between the Taiwanese Austronesians and the Tai-Kadai peoples of Southern China.

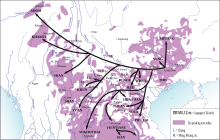

[12][13] The Tai peoples, from Guangxi began moving south – and westwards in the first millennium CE, eventually spreading across the whole of mainland Southeast Asia.

[18] Based on layers of Chinese loanwords in proto-Southwestern Tai and other historical evidence, Pittayawat Pittayaporn (2014) proposes that the southwestward migration of southwestern Tai-speaking tribes from the modern Guangxi to the mainland of Southeast Asia must have taken place sometime between the 8th–10th centuries.

[19] Tai speaking tribes migrated southwestward along the rivers and over the lower passes into Southeast Asia, perhaps prompted by the Chinese expansion and suppression.

[20] Two years later, another Li chief named Chen Xingfan declared himself the Emperor of Nanyue and led a large uprising against the Chinese, but was also crushed by Yang Zixu, who beheaded 60,000 rebels.

The third and major migration direction crossed the valleys of the Red and Black River, heading west through the hills into Burma and Assam.

[23] As a result of these three bloody centuries,[21] or with the political and cultural pressures from the north, some Tai peoples migrated southwestward, where they met the classical Indianized civilizations of Southeast Asia.

Du Yuting and Chen Lufan from Kunming Institute Southeast Asian Studies claimed that, during the Western Han dynasty, ancestors of the Tai people were known as Dianyue (in today Yunnan).

[26][27][28][29] Additionally, Du & Chen rejected the proposal that the ancestors of Tai people migrated en masse southwestwards out of Yunnan only after the 1253 Mongol invasion of Dali.

[34]: 28 The Tai people were the predominant non-Khmer groups in the areas of central Thailand that formed the geographical periphery of the Khmer Empire.

"[38] During the Ming dynasty in China, attempts were made to subjugate, control, tax, and settle ethnic Han along the lightly populated frontier of Yunnan with Southeast Asia (modern-day Burma, Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam).

It is natural that when China is governed peacefully, foreign countries would come and submit (來附)”…I am anxious that, as you are secluded in your distant places, you have not yet heard of my will.

Chinese epigraphic materials from Chu texts show clear substrate influence predominantly from Tai-Kadai, and a few items of Austroasiatic and Hmong-Mien origin.

[58] The Tai practice a type of feudal governance that is fundamentally different from that of the Han Chinese people, and is especially adapted to state formation in ethnically and linguistically diverse montane environments centered on valleys suitable for wet-rice cultivation.

The Tai village consisted of nuclear families working as subsistence rice farmers, living in small houses elevated above the ground.