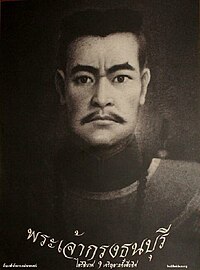

Taksin

His reign was characterized by numerous wars; he fought to repel new Burmese invasions and to subjugate the northern Thai kingdom of Lanna, the Laotian principalities, and threatening Cambodia.

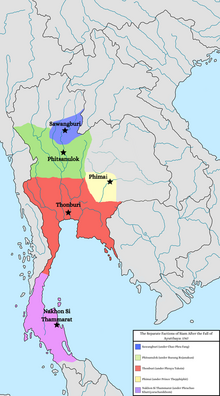

He was taken in a coup d'état and executed, and succeeded by his long-time friend Maha Ksatriyaseuk, who then assumed the throne, founding the Rattanakosin Kingdom and the Chakri dynasty, which has since ruled Thailand.

His father, Yong Saetae (Thai: หยง แซ่แต้; Chinese: 鄭鏞 Zhèng Yōng), who worked as a tax-collector,[7] was of ethnic Teochew descent from Chenghai District, Shantou, Guangdong, China.

When Sin and his friend Thongduang who was also a descendant of Mon aristocratic family were Buddhist novices, they reportedly met a Chinese fortune-teller who told them that both had lucky lines in their hands and would both become kings.

[citation needed] On 3 January 1767, 3 months before the fall of Ayutthaya,[16] Taksin made his way out of the city at the head of 500 followers to Rayong, on the east coast of the Gulf of Thailand.

He travelled first to Chonburi, a town on the Gulf of Thailand's eastern coast, and then to Rayong, where he raised a small army and his supporters began to address him as Prince Tak.

[21] His army was rapidly increasing in numbers, as men of Chanthaburi and Trat, which had not been plundered and depopulated by the Burmese,[22] naturally constituted a suitable base for him to make preparations for the liberation of his motherland.

[23] Having thoroughly looted Ayutthaya, the Burmese did not seem to show serious interest in holding the capital of Siam, since they left only a handful of troops under General Suki to control the shattered city.

On 6 November 1767, having amassed 5,000 troops and built 100 ships, Taksin sailed up the Chao Phraya River and seized Thonburi opposite present day Bangkok.

[25] He followed up his victory quickly by attacking the main Burmese camp numbering 3,000 men, led by General Suki (สุกี้) at the Battle of Pho Sam Ton (Thai: โพธิ์สามต้น) near Ayutthaya.

[29] Not only would Thonburi be difficult to invade by land, it would also prevent an acquisition of weapons and military supplies by anyone ambitious enough to establish himself as an independent prince further up the Chao Phraya River.

[21] As Thonburi was a small town, Taksin's available forces, both soldiers and sailors, could man its fortifications, and if he found it impossible to hold it against an enemy attack, he could embark the troops and retreat to Chanthaburi.

Among the officials who cast their fate with him during the campaigns for independence and for the elimination of the self-appointed local nobles were two personalities who subsequently played important roles in Thai history.

[31] Thongduang, prior to the sacking of Ayutthaya, was ennobled as Luang Yokkrabat, taking charge of royal surveillance, serving the Governor of Ratchaburi, and Bunma had a court title conferred upon him as Nai Sudchinda.

[41][42] Undaunted by this defeat, and aiming to retake Chiang Mai, Hsinbyushin tried again to conquer Siam, and in October 1775 the greatest Burmese invasion in the Thonburi period began under Maha Thiha Thura, known in Thai history as Azaewunky.

[46] In 1777, the ruler of Champasak, which was at that time an independent principality bordering the eastern frontier of the Thonburi Kingdom, supported the Governor of Nangrong, who had rebelled against the King Taksin.

In Vientiane, a Minister of State, Pra Woh [de], had rebelled against the ruling prince and fled to the Champasak territory, where he set himself up at Donmotdang, near the present city of Ubon Ratchathani.

This action was instantly regarded by King Taksin as a great insult to him, and at his command, Somdej Chao Phraya Mahakasatsuek invaded Vientiane with an army of 20,000 men in 1778.

He paid high prices for rice from his own money to induce foreign traders to bring in adequate amounts of basic necessities to satisfy the need of the people.

During this time King Taksin actively encouraged the Chinese to settle in Siam, principally those from Chaoshan,[54] partly with the intention to revive the stagnating economy[55] and upgrading the local workforce.

The opposition was led mainly by the Bunnags, a merchant-aristocratic family of Persian origin, successors of Ayutthaya's minister of Ports and Finance, or Phra Klang[57] Later, Thonburi ordered some guns from England.

Royal letters were exchanged and in 1777 the Viceroy of British Raj Madras, George Stratton, sent a gold scabbard decorated with gems to King Taksin.

The administration of the Sangha during the Thonburi period followed the model established in Ayutthaya,[63] and he allowed French missionaries to enter Thailand, and like a previous Thai king, helped them build a church in 1780.

However, his attempt was hindered by Mạc Thiên Tứ (Mo Shilin), the governor of Hà Tiên, whom had thorough knowledge of Chinese diplomatic practices and alleged that Taksin was a usurper.

"[68] As one contemporary observed, François Henri Turpin (1771), under the famine conditions of 1767–1768 : A tomb containing Taksin's clothes and a family shrine were found at Chenghai district in Guangdong province in China in 1921.

[75] An alternative account (by the Official Vietnamese Chronicles) states that Taksin was ordered to be executed in the traditional Siamese way by General Chao Phraya Chakri at Wat Chaeng: by being sealed in a velvet sack and beaten to death with a scented sandalwood club.

[76] Another account claimed that Taksin was secretly sent to a palace located in the remote mountains of Nakhon Si Thammarat, where he lived until 1825, and that a substitute was beaten to death in his place.

Resentful, the brothers eventually befriended two Vietnamese generals, Nguyễn Hữu Thoại (阮有瑞) and Hồ Văn Lân (胡文璘), the four swearing to help with each other in need.

According to Nidhi Eoseewong, a prominent Thai historian, writer, and political commentator, Taksin could be seen as the originator, new style of leader, promoting a 'decentralized' kingdom and new generation of the nobles, of Chinese merchant-origin, his major helpers in the wars.

This was because the leaders of that time such as Plaek Phibunsongkhram and even later military junta, on the other hand, wanted to glorify and publicize the stories of certain historical figures in order to support their own policy of nationalism, expansionism and patriotism.