Tang dynasty tomb figures

The figures, called mingqi in Chinese, were most often of servants, soldiers (in male tombs) and attendants such as dancers and musicians, with many no doubt representing Gējìs.

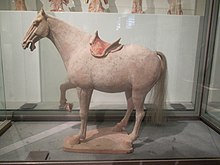

The animals are most often horses, but there are surprising numbers of both Bactrian camels and their Central Asian drivers, distinguished by thick beards and hair, and their facial features.

The depictions are realistic to a degree unprecedented in Chinese art,[3] and the figures give archaeologists much useful information about life under the Tang.

[8] They "virtually disappear" from 755 when the highly disruptive An Lushan Rebellion began,[9] which probably affected the kilns in Henan and Hebei making the pieces as well as their elite clientele.

[13] A thousand years before the Tang figures, the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (d. about 433 BC) contained the bodies of 22 musicians, as well as the instruments they played.

[14] Traces of wooden figures wearing textiles are known from similar dates, and the First Emperor's Terracotta Army is famous;[15] his funeral also involved the killing and burial of many servants and animals, including all his childless concubines.

It had been robbed in the past, probably soon after the burial, but the thieves had not bothered with the 777 unglazed and painted and around 60 glazed tomb figures (now mostly Shaanxi History Museum).

[23] Grand tombs were conceived as "a personalized paradise mirroring the best aspects of the earthly world", approached by a spirit road with stone statues, and ministered to by priests in temples and altars around the mound.

[24] Underground, they also contained extensive frescos with painted representations of the same types of figure as the pottery, and the images in the two media worked together to recreate a palace geography evoking the residence and lifestyle of the deceased before death.

The clay body fires to a "whitish" colour, except for a smaller group of less fine reddish pieces, normally covered in white slip.

[38] The figures share with Buddhist monumental sculpture of the period conventions, derived from further west, that show "appropriate detail of muscle which yet departs from reality at many points".

[39] With exception of the Zodiac figures, which were also the only type to increase in popularity after the Tang, the figures are "more closely related to the metropolitan and Buddhist attitudes than to the magical aspects of rural beliefs and a pattern of behaviour governed by superstitions or shamanistic beliefs of the local farming communities", which partly accounts for their failure to return after the 750s,[40] along with a preference for new types of grave goods.

[44] It has been suggested that this change in taste was provoked by the famous imperial concubine Yang Guifei, who had a full figure, although it seems to begin by about 725,[45] when she was a child.

More rarely, there are female riders and polo players, wearing male dress, which was usual for Tang women when riding, and apparently a fashion in the capital on other occasions.

Foreigners from further west seem to have been common as servants, in particular as grooms for horses and drivers of the camels which were the main form of transport on the overland Silk Road.

Tang art liked to depict foreign figures, usually men, with standard characteristics for their faces and dress; Persian and Sogdian types can be distinguished, both with big bushy beards, and often fierce and vigorous expressions.

Both sorts range from animals without harness and saddlery to those with elaborately detailed trappings, and carrying riders or, in the case of camels, heavy loads of goods.

They are often shown with heads raised and their mouths open, and in the finest models the shaggy areas at the neck and top of the legs are carefully textured in the clay.

These too were shown as "a fabulous crested semi-human being with bulging eyes, furiously gaping mouth and massive powerful arms and legs".

[65] Whereas the Indian versions emphasized royal attributes, in China they were "transformed into dynamic idealized generals",[66] with elaborate armour, often with added sprigged reliefs.

In the early part of the Tang their pose was less dramatic, standing with straight legs and holding a weapon (now usually lost) at rest.