Celadon

[2] Celadon production later spread to other parts of East Asia, such as Japan and Korea,[3] as well as Southeast Asian countries, such as Thailand.

Celadon continued to be produced in China at a lower level, often with a conscious sense of reviving older styles.

The celadon color is classically produced by firing a glaze containing a little iron oxide at a high temperature in a reducing kiln.

Too little iron oxide causes a blue color (sometimes a desired effect), and too much gives olive and finally black; the right amount is between 0.75% and 2.5%.

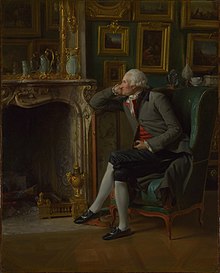

The most commonly accepted theory is that the term first appeared in France in the 17th century and that it is named after the shepherd Celadon in Honoré d'Urfé's French pastoral romance L'Astrée (1627),[5] who wore pale green ribbons.

So-called "true celadon", which requires a minimum 1,260 °C (2,300 °F) furnace temperature, a preferred range of 1,285 to 1,305 °C (2,345 to 2,381 °F), and firing in a reducing atmosphere, originated at the beginning of the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127),[7] at least on one strict definition.

Celadons are almost exclusively fired in a reducing atmosphere kiln as the chemical changes in the iron oxide which accompany depriving it of free oxygen are what produce the desired colors.

[12] This had bluish, blue-green, and olive green glazes and the bodies increasingly had high silica and alkali contents which resembled later porcelain wares made at Jingdezhen and Dehua rather than stonewares.

Other wares which can be classified as celadons, were more often in shades of pale blue, very highly valued by the Chinese, or various browns and off-whites.

Since about 1420 the Counts of Katzenelnbogen have owned the oldest European import of celadon, reaching Europe indirectly via the Islamic world.

There is very rarely any contrast with a completely different color, except where parts of a piece are sometimes left as unglazed biscuit in Longquan celadon.

Even though Japan has arguably the most diverse styles of ceramic art in the modern era, greenware was mostly avoided by potters because of the high loss rate of up to 80%.

Nevertheless, a number of artists emerged whose works received critical acclaim in regards to the quality and color of the glazes achieved, as well as later on in the innovation of modern design.

The glaze with a mixed subtle color gradations of icy, bluish white is called seihakuji (青白磁) porcelain.

Artists from the early Showa era are Itaya Hazan (1872–1963), Tomimoto Kenkichi (1886–1963), Kato Hajme (1900–1968), Tsukamoto Kaiji (塚本快示) (1912–1990), and Okabe Mineo (1919–1990), who specialized in Guan ware with its crackled glaze.

Artists such as Fukami Sueharu, Masamichi Yoshikawa, and Kato Tsubusa also produce abstract pieces, and their works are part of a number of national and international museum collections.

Korea has a tradition of making jewels and crowns with jade in gogok shapes as a symbol of creativity, universe, divinity, and leadership.

Mountains in the north provided the necessary raw materials such as firewood, kaolin and silicon dioxide for the master potters while a well established system of distribution transported pottery throughout Korea and facilitated export to China and Japan.

Beginning in the early 20th century, potters, using modern materials and tools, attempted to recreate the techniques of ancient Korean Goyeo celadons.

Playing a leading role in its revival was Yu Geun-Hyeong (유근형; 柳根瀅), a Living National Treasure whose work was documented in the 1979 short film, Koryo Celadon.

[30] In the late 20th century ceramists like Shin Sang-ho and Kim Se-yong created their own styles based upon traditional Goryeo ware.

Medieval Thai wares were initially influenced by Chinese greenware, but went on to develop its own unique style and technique.

[32] Outside of East Asia, a number of artists also worked with greenware to varying degrees of success in regard to purity and quality.