Tank cascade system

It is a network of thousands of small irrigation tanks (Sinhala: වැව, romanized: wewa) draining to large reservoirs that store rainwater and surface runoff for later use.

[8] The tank cascade system is largely located in the semi-arid north-central section of the island, which experiences equatorial heat, limited freshwater, and erratic rainfall patterns.

"[14][15] Similar ancient water engineering projects in tropical and subtropical climates include the qanats of Iran, oases in the Near East and North Africa, and the Gurganj Dam of Amu Darya.

[12] Researchers theorise that the evolution of the tank cascade began with rain-fed agriculture and then became increasingly sophisticated beginning with diverting rivulets, then permanent rivers, followed by a leap forward with the construction of spillways, weirs and ultimately sluices, then the construction of reservoirs, until, at the apogee of development, ancient Sri Lankans were able to successfully dam up perennial rivers and use the water as they saw fit.

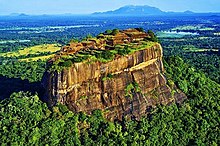

[17] The most famous surviving exemplars of the irrigation infrastructure used by Sri Lankan elites are the Abhayavapi rainwater reservoir in Anuradhapura built by Pandukabhaya (437–366 BCE) and the "lion rock" fortress Sigiriya, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The only possible source of water at Sigiriya (which sits 360 meters atop the plain) is rainwater, which was cunningly managed through a network of pools, underground channels and drains.

"[10] The extensive tank cascade infrastructure incorporated local and regional Buddhist monasteries by providing them with their own irrigation access and related incomes.

[20] In contemporary Sri Lanka, "Buddhist monks of any given village…are often consulted on water management decisions and lead agro-based cultural festivities.

Dutch colonial administrators (1640–1796 CE) mostly concerned themselves with cultivation of coastal areas and lucrative crops like cinnamon and seem to have ignored the inland tank cascade systems.

[22] British records also tell of village irrigation managers creating sluices from hollow tree trunks or clay pots turned pipes.

[21] Tanks can be any size from small vernal pools to huge perennial lakes "thousands of hectares in surface area.

[27] The gosgommana may be planted with indigenous species including Bassia longifolia, Terminalia arjuna, Crateva adansonii and Diosoyros malabarica.

"[11] The system remains an important part of the modern Sri Lankan irrigation network, and supports much of the agriculture in the country.

[21] Larger reservoirs may have buildings or huts built along the shore, and may be used for freshwater fishing, hunting or poaching, and lotus flower picking, in addition to the typical agricultural and pastoral uses.

[32] Benefits of the tank cascade system include creating cooler microclimates that serve as wildlife habitats, encouraging biodiversity through the establishment of many ecological niches and ecotones, and establishing conditions for a "unique decentralized social system in Sri Lanka where farmers have held the highest social rank.

"[1] The tanks and connecting channels are used as water sources and habitat by both domestic livestock and indigenous wildlife, including Sri Lankan elephants.

[33][26] A biodiversity survey of just one tank cascade system in the Malwathu Oya river watershed found that it supported approximately 400 plant and animal species.