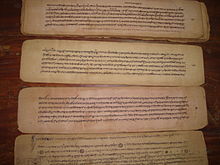

Buddhist tantric literature

The earliest of these works are a genre of Indian Buddhist tantric scriptures, variously named Tantras, Sūtras and Kalpas, which were composed from the 7th century CE onwards.

[1] They are followed by later tantric commentaries (called pañjikās and ṭīkās), original compositions by Vajrayana authors (called prakaraṇas and upadeśas), sādhanas (practice texts), ritual manuals (kalpas or vidhis), collections of tantric songs (dohās) odes (stotra), or hymns, and other related works.

[4] Wu-xing also reports that at the time he visited India (7th century), the Mantrayāna (“teaching about mantra”, Chinese: zhenyan jiaofa, 真言教法) was already very popular.

[6] Over time the number of texts increased with numerous Tantric scholars writing commentaries and practice manuals.

[8] Buddhist tantras were also influenced by non-buddhist traditions, including Śaiva and Śakta sources, the cults of local deities, and rites related to yakshas and nāgas.

[13] Later Tantric texts from the eighth century onward (termed variously Yogatantra, Mahayoga, and Yoginī Tantras) advocated union with a deity (deity yoga), sacred sounds (mantras), techniques for manipulation of the subtle body and other secret methods with which to achieve swift Buddhahood.

[16] Other origin myths focus around a mythic king of Oḍiyāna named Indrabhūti, who received the tantras with the aid of Vajrapani.

In another text meanwhile, Vilāsavajra discusses a different third category: Upaya, which referred to more transgressive tantras that made use of sexual yoga.

[20] A fourfold schema can be found in the work of the Indian scholar Śraddhākaravarman, who writes of "four doors" to the Vajratana: Kriyatantra, Caryatantra, Yoga- tantra, and Mahayogatantra.

[23] Many tantric Buddhist texts have titles other than "Tantra", including sutra, kalpa, rajñi, stotra, and doha.

Indeed, some scholars like Koichi Shinohara argue that the Buddhist tantric literature grew out of the earlier Mahayana dhāraṇī texts through a process of gradual expansion and the incorporation of new ritual elements (such as mandalas and visualization practices).

They often omit important details and misdirect the reader, thus maintaining secrecy and requiring further commentary to be properly understood.

[31] Buddhist tantras promise both the ability to attain worldly magical powers (laukikasiddhi) and the surepeme achievement (lokottarasiddhi) of Buddhahood in one lifetime.

[32][3] The tantras also contain a revaluation of supposedly negative mental states (like desire and anger) and antinominan behavior (like drinking alcohol, eating meat, living in charnel grounds etc.

[34][35] According to the tantras, to reach Buddhahood, one needs to recognize the true nature of one's mind, the buddha-nature, which is a non-dual empty luminosity (prabhāsvara) which is pure, blissful, and free of all concepts.

Common topics related to spiritual practice include: how to make mandalas, how to perform ritual initiations (abhisheka), explanation of mantras, fire ritual (homa), special observances (carya), descriptions of tantric feasts (ganacakra), descriptions of tantric deities, deity yoga, subtle body based practices (of the perfection stage) and teachings on the yoginis.

[33] Japanese scholars like Tsukamoto further classify these into different families, like Akṣobhya-kula, Vairocana-kula, Heruka-kula, Vajra-sūrya-kula, Padmanarteśvara-kula, Paramāśva-kula, and Vajradhara-kula.

Some key tantras in this category include:[46] There are various other types of tantric Buddhist texts composed in India.

Sāṅkrtyāyana lists the following important siddhas: Saraha, (Nāgārjuna), (Sabarapa), Luīpa, Dārikāpa, (Vajra-ghaṇṭāpa), Kūrmapā, Jālandharapā, (Kaṃha(pā) Caryapā), Guhyapā (Vijayapa), Tilopa, Naropa.

Benoytosh Bhattacharyya notes that there are two main chronological lists of prominent Indian Tantric authors, the first from Tāranātha's works (c. 1575–1634) and the second from Kazi Dawasamdup's introduction to the Cakrasaṃvara Tantra.

They worked on translations of classic tantras like the Vairocanābhisaṃbodhi Sūtra and the Vajrasekhara Sutra, and also composed practice manuals and commentaries in Chinese.

[66] They are considered to be the founding patriarchs of Chinese Esoteric Buddhism and their writings are central to the East Asian Mantrayāna traditions.

The tradition was passed on from later figures like Huiguo to various Japanese Buddhist disciples who founded the Mantrayāna lineages in Japan.

One of the most important works of Kūkai is his magnum opus, the Jūjū shinron (Treatise on Ten Levels of Mind), along with its summary, the Hizō hōyaku (Precious Key to the Secret Treasury).

[67] The Tendai school meanwhile also maintains its own collection of Mantrayāna texts, commentaries and practice manuals, composed by traditional figures like Saicho, Ennin and Annen.

are particularly important for Tendai esotericism, especially his Shingonshū kyōjigi (On the Meaning of Teachings and Times in Esoteric Buddhism) and the Taizōkongō bodaishingi ryaku mondōshō (Abbreviated Discussion on the Meaning of Bodhicitta according to the Garbha and Vajra realms) [68] As Vajrayana Buddhism developed in Tibet (beginning in the 8th century CE), Tibetan Buddhists also began to compose Vajrayana scriptures, commentaries and other works.

Each school of Tibetan Buddhism maintains their own collections of texts composed by the lineage masters of their tradition and considered to be canonical by their sect.

The Nyingma school for example, maintains a large collection of texts which are part of their "Dzogchen" (Great Perfection) tradition.

The Kagyu tradition emphasizes the esoteric practice of Mahamudra, and as such, they also maintain many collections of texts that focus on this method.

[70] In the Gelug school, the tantric works of the founder Tsongkhapa and his direct disciples are generally seen as foundational texts.