Taoist philosophy

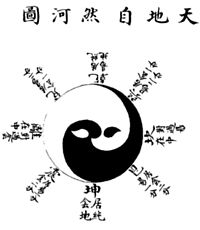

'self-so', "natural authenticity"), qì ("spirit"), wú ("non-being"), wújí ("non-duality"), tàijí ("polarity") and yīn-yáng (lit.

"[5] Instead of drawing on a single book or the works of one founding teacher, Taoism developed out a widely diverse set of Chinese beliefs and texts, that over time were gathered together into various synthetic traditions.

[8] Likewise the labels Taoism and Confucianism were developed during the Han dynasty by scholars to group together various thinkers, and texts of the past and categorize them as "Taoist", even though they are quite diverse and their authors may never have known of each other.

[12] The Daodejing changed and developed over time, possibly from a tradition of oral sayings, and is a loose collection of aphorisms on various topics which seek to give the reader wise advice on how to live and govern, and also includes some metaphysical speculations.

[13] Some scholars have argued that the Daodejing prominently refers to a subtle universal phenomenon or cosmic creative power called Dào (literally "way" or "road"), using feminine and maternal imagery to describe it.

[3] The Daodejing also mentions the concept of wúwéi (effortless action), which is illustrated with water analogies (going with the flow of the river instead of against it) and "encompasses shrewd tactics—among them “feminine wiles”— which one may utilize to achieve success".

Wúwéi is the activity of the ideal sage (shèng-rén), who spontaneously and effortlessly express dé (virtue), acting as one with the universal forces of the Dào, resembling children or un-carved wood (pu).

Sages concentrate their internal energies, are humble, pliable, and content; and they move naturally without being restricted by the structures of society and culture.

[18] The Neiye's idea of a pervasive and unseen "spirit" called qì and its relationship to acquiring dé (virtue or inner power) was very influential for later Taoist philosophy.

[22] The Zhuangzi's vision for becoming a sage requires one to empty oneself of conventional social values and cultural ideas and to cultivate wúwéi.

According to Livia Kohn, tiān is "a process, an abstract representation of the cycles and patterns of nature, a nonhuman force that interacted closely with the human world in a nonpersonal way.

"[24] The term Daojia (usually translated as "philosophical Taoism") was coined during the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) by scholars and bibliographers to refer to a grouping of classic texts like the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi.

[26] Another influence to the development of later Taoism was Huáng-Lǎo (literally: "Yellow [Emperor] Old [Master]"), one of the most influential Chinese school of thought in the early Han dynasty (2nd-century BCE).

These intellectual currents helped inspire several new social movements such as the Way of the Celestial Masters which would later influence Taoist thought.

[28] It was the Lingbao school who also developed the ideas of a great cosmic deity as a personification of the Tao and a heavenly order with Mahayana Buddhist influences.

[3] Thinkers like He Yan and Wang Bi set forth the theory that everything, including yīn and yáng and the virtue of the sage, “have their roots" in wú (nothingness, negativity, not-being).

Like He Yan, Wang Bi focuses on the concept of wú (non-being, nothingness) as the nature of the Tao and underlying ground of existence.

[30] According to Livia Kohn, for Wang Bi "nonbeing is at the root of all and needs to be activated in a return to emptiness and spontaneity, achieved through the practice of nonaction, a decrease in desires and growth of humility and tranquility".

[30] During the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589), Xuanxue reached the height of influence as it was admitted into the official curriculum of the imperial academy.

The Song dynasty (960–1279) era saw the foundation of the Quanzhen (Complete perfection or Integrating perfection) school of Taoism during the 12th century among followers of Wang Chongyang (1113–1170), a scholar who wrote various collections of poetry and texts on living a Taoist life who taught that the "three teachings" (Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism), "when investigated, prove to be but one school".

Wang Chongyang taught that “immortality of the soul” (shén-xiān, 神仙) can be attained within this life by entering seclusion, cultivating one's “internal nature” (xìng, 性), and harmonizing them with one's “personal fate” (mìng-yùn, 命運).

"[38] He taught that, by mental training and asceticism through which one reaches a state of no-mind (wú-xīn, 無心) and no-thoughts, attached to nothing, one can recover the primordial, deathless "radiant spirit" or "true nature" (yáng-shén 陽神, zhēn-xìng 真性).

Fond as he was of borrowing Buddhist language to preach detachment from this provisional, fleeting world of samsara, Wang Zhe ardently believed in the eternal, universal Real Nature/Radiant Spirit that is the ground and wellspring of consciousness (spirit [shén], Nature [xíng]), and vitality (qì, Life [mìng]) within all living beings.

[41] Several Song emperors, most notably Huizong, were active in promoting Taoism, collecting Taoist texts and publishing editions of the Daozang.

[43] During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the state promoted the notion that “the Three Teachings (Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism) are one”, an idea which over time became popular consensus.

[46] The late Ming and early Qing dynasty saw the rise of the Longmen ("Dragon Gate" 龍門) school of Taoism, founded by Wang Kunyang (d. 1680) which reinvigorated the Quanzhen tradition.

[47] It was Min Yide who also made the famous text known as The Secret of the Golden Flower, along with its emphasis on internal alchemy, the central doctrinal scripture of the Longmen tradition.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Taoism had declined considerably, and only one complete copy of the Daozang still remained, at the White Cloud Monastery in Beijing.