Chinese theology

The alignment of earthly and heavenly forces is upheld through the practice of rites and rituals (Li), for instance, the jiao festivals in which sacrificial offerings of incense and other products are set up by local temples, with participants hoping to renew the perceived alliance between community leaders and the gods.

[13][14] As explained by the scholar Stephan Feuchtwang, in Chinese cosmology "the universe creates itself out of a primary chaos of material energy" (hundun and qi), organising as the polarity of yin and yang which characterises any thing and life.

Yin and yang are the invisible and the visible, the receptive and the active, the unshaped and the shaped; they characterise the yearly cycle (winter and summer), the landscape (shady and bright), the sexes (female and male), and even sociopolitical history (disorder and order).

As long as it is blowing wind, raining, thundering, or flashing, [we call it] shén, while it stops, [we call it] gǔi.The Chinese dragon, associated with the constellation Draco winding the north ecliptic pole and slithering between the Little and Big Dipper (or Great Chariot), represents the "protean" primordial power, which embodies both yin and yang in unity,[18][failed verification] and therefore the awesome unlimited power (qi) of divinity.

That is to say, each creature plays both the roles of creature and creator, and consequently is not only a fixed constituent of, but also a promoter and author of, the diversity or richness of the world.The relationship between oneness and multiplicity, between the supreme principle and the myriad things, is notably explained by Zhu Xi through the "metaphor of the moon":[24] Fundamentally there is only one Great Pole (Tàijí), yet each of the myriad things has been endowed with it and each in itself possesses the Great Ultimate in its entirety.

It cannot be said that the moon has been split.In his terminology, the myriad things are generated as effects or actualities (用 yòng) of the supreme principle, which, before in potence (體 tǐ), sets in motion qi.

[5] Other words, such as 顶 dǐng ("on top", "apex") would share the same etymology, all connected to a conceptualisation—according to the scholar John C. Didier—of the north celestial pole godhead as cosmic square (Dīng 口).

[43] Medhurst (1847) also shows affinities in the usage of "deity", Chinese di, Greek theos and Latin deus, for incarnate powers resembling the supreme godhead.

[44] Ulrich Libbrecht distinguishes two layers in the development of early Chinese theology, traditions derived respectively from the Shang and subsequent Zhou dynasties.

[40] In the Shang dynasty, as discussed by John C. Didier, Shangdi was the same as Dīng (口, modern 丁), the "square" as the north celestial pole, and Shàngjiǎ (上甲 "Supreme Ancestor") was an alternative name.

[54] The other gods associated with the circumpolar stars were all embraced by Shangdi, and they were conceived as the ancestors of side noble lineages of the Shang and even non-Shang peripheral peoples who benefited from the identification of their ancestor-gods as part of Di.

[53] The emperors of the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) are credited with an effort to unify the cults of the Wǔfāng Shàngdì (五方上帝 "Five Forms of the Highest Deity"), which were previously held at different locations, into single temple complexes.

They "reflect the cosmic structure of the world" in which yin, yang, and all forces are held in balance, and are associated with the four directions of space and the centre, the five sacred mountains, the five phases of creation, and the five constellations rotating around the celestial pole and five planets.

The competing factions of the Confucians and the fāngshì (方士 "masters of directions"), regarded as representatives of the ancient religious tradition inherited from previous dynasties, concurred in the formulation of the Han state religion.

[62] Throughout the Qin and the Han dynasties, a distinction became evident between Taiyi as the supreme godhead identified with the northern culmen of the sky and its spinning stars, and a more abstract concept of Yī (一 "One"), which begets the polar godhead bringing into existence the principles of Yin and Yang, the pivot san bao, then "the myriad of beings" and "the ten thousand things"; the more abstract Yi was an "interiorisation" of the supreme God which was influenced by the Confucian discourse.

[58] As a human being, the Yellow Emperor was conceived by a virgin mother, Fubao, who was impregnated by Taiyi's radiance (yuanqi, "primordial pneuma"), a lightning, which she saw encircling the Northern Dipper (Great Chariot, or broader Ursa Major), or the celestial pole, while walking in the countryside.

[84] By the Tang dynasty the name of "Jade King" had been widely adopted by the common people to refer to the God of Heaven, and this got the attention of the Taoists who integrated the deity in their pantheon.

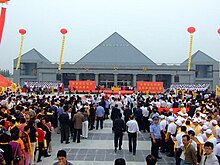

[85] There are a great number of temples in China dedicated to the Jade Deity (玉皇庙 yùhuángmiào or 玉皇阁 yùhuánggé, et al.), and his birthday on the 9th day of the first month of the Chinese calendar is one of the biggest festivals.

[88] Zi 子, literally meaning "son", "(male) offspring", is another concept associated with the supreme God of Heaven as the north celestial pole and its spinning stars.

According to Didier, in Shang and Zhou forms, the grapheme zi itself depicts someone linked to the godhead of the squared north celestial pole (口 Dīng), and is related to 中 zhōng, the concept of spiritual, and thus political, centrality.

His elaboration of ancient theology gives centrality to self-cultivation and human agency,[46] and to the educational power of the self-established individual in assisting others to establish themselves (the principle of 愛人 àirén, "loving others").

[110] The theistic idea of early Confucianism gave later way to a depersonalisation of Heaven, identifying it as the pattern discernible in the unfolding of nature and his will (Tianming) as peoples' consensus, culminating in the Mencius and the Xunzi.

[114] According to the further explanations of Xiong's student Mou Zongsan, Heaven is not merely the sky, and just like the God of the Judaic and Hellenistic-Christian tradition, it is not one of the beings in the world.

[132] While Confucians prescribe to be moderate in pursuing appetites, since even the bodily ones are necessary for life,[133] when the "proprietorship of corporeality" (xíngqì zhīsī 形氣之私) prevails, selfishness and therefore immorality ensue.

By all these methods it stimulates his mind, hardens his nature, and supplies his incompetencies.Likewise, Zhu Xi says:[128] Helplessness, poverty, adversity, and obstacles can strengthen one's will, and cultivate his humanity (ren).Religious traditions under the label of "Taoism" have their own theologies which, characterised by henotheism, are meant to accommodate local deities in the Taoist celestial hierarchy.

[15] It has hermetic and lay liturgical traditions, the most practised at the popular level being those for healing and exorcism, codified into a textual corpus commissioned and approved by emperors throughout the dynasties, the Taoist Canon.

[138] The hierarchy of the highest powers of the cosmos is arranged as follows:[32] Interest in traditional Chinese theology has waxed and waned throughout the dynasties of the history of China.

[13] Most people in China today take part in some rituals and festivals, especially those around the lunar new year,[139] and culture heroes like the Yellow Emperor are celebrated by the contemporary Chinese government.

Their organizational form and its symbols are sacred in their concreteness, regardless of ... speculations about their meaning.Quoting from Ellis Sandoz's works, Hsu says:[104] Civil theology consists of propositionally stated true scientific knowledge of the divine order.

It is the theology discerned and validated through reason by the philosopher, on the one hand, and through common sense and the logique du Coeur evoked by the persuasive beauty of mythic narrative and imitative representations, on the other hand.Also, Joël Thoraval characterises the common Chinese religion, or what he calls a "popular Confucianism", which has powerfully revived since the 1980s, consisting of the widespread belief and worship of five cosmological entities—Heaven and Earth (Di 地), the sovereign or the government (jūn 君), ancestors (qīn 親), and masters (shī 師)—, as China's civil religion.

.

.