Taoism

Early Taoism drew upon diverse influences, including the Shang and Zhou state religions, Naturalism, Mohism, Confucianism, various Legalist theories, as well as the I Ching and Spring and Autumn Annals.

[18] But the earliest references to 'the Tao' per se are largely devoid of liturgical or explicitly supernatural character, used in contexts either of abstract metaphysics or of the ordinary conditions required for human flourishing.

Scholars like Harold Roth argue that early Taoism was a series of "inner-cultivation lineages" of master-disciple communities, emphasizing a contentless and nonconceptual apophatic meditation as a way of achieving union with the Tao.

[4] According to modern scholars of Taoism, such as Kirkland and Livia Kohn, Taoist philosophy also developed by drawing on numerous schools of thought from the Warring States period (4th to 3rd centuries BCE), including Mohism, Confucianism, Legalist theorists (like Shen Buhai and Han Fei, which speak of wu wei), the School of Naturalists (from which Taoism draws its main cosmological ideas, yin and yang and the five phases), and the Chinese classics, especially the I Ching and the Lüshi Chunqiu.

[64] Another important early Taoist movement was Taiqing (Great Clarity), which was a tradition of external alchemy (weidan) that sought immortality through the concoction of elixirs, often using toxic elements like cinnabar, lead, mercury, and realgar, as well as ritual and purificatory practices.

[citation needed] The Three Kingdoms period saw the rise of the Xuanxue (Mysterious Learning or Deep Wisdom) tradition, which focused on philosophical inquiry and integrated Confucian teachings with Taoist thought.

Thus, according to Russell Kirkland, "in several important senses, it was really Lu Hsiu-ching who founded Taoism, for it was he who first gained community acceptance for a common canon of texts, which established the boundaries, and contents, of 'the teachings of the Tao' (Tao-chiao).

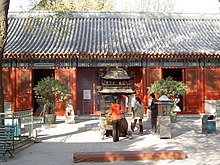

[87] In the 12th century, the Quanzhen (Complete Perfection) School was founded in Shandong by the sage Wang Chongyang (1113–1170) to compete with religious Taoist traditions that worshipped "ghosts and gods" and largely displaced them.

[96] Under the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), aspects of Confucianism, Taoism, and East Asian Buddhism were consciously synthesized in the Neo-Confucian school, which eventually became Imperial orthodoxy for state bureaucratic purposes.

[82] The Ming era saw the rise of the Jingming ("Pure Illumination") school to prominence, which merged Taoism with Buddhist and Confucian teachings and focused on "purity, clarity, loyalty and filial piety".

[103] The Qing era also saw the birth of the Longmen ("Dragon Gate" 龍門) school of Wang Kunyang (1552–1641), a branch of Quanzhen from southern China that became established at the White Cloud Temple.

[106] The Longmen school synthesized the Quanzhen and neidan teachings with the Chan Buddhist and Neo-Confucian elements that the Jingming tradition had developed, making it widely appealing to the literati class.

[120] Regarding the status of Taoism in mainland China, Livia Kohn writes: Taoist institutions are state-owned, monastics are paid by the government, several bureaus compete for revenues and administrative power, and training centers require courses in Marxism as preparation for full ordination.

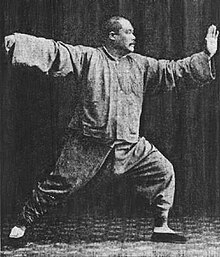

Kohn notes that all of these centers "combine traditional ritual services with Tao Te Ching and Yijing philosophy as well as with various health practices, such as breathing, diet, meditation, qigong, and soft martial arts".

[183] Many Taoist practices work with ancient Chinese understandings of the body, its organs and parts, "elixir fields" (dantien), inner substances (such as "essence" or jing), animating forces (like the hun and po), and meridians (qi channels).

Arthur Waley, applying them to the socio-political sphere, translated them as: "abstention from aggressive war and capital punishment", "absolute simplicity of living", and "refusal to assert active authority".

[203] In its original form, the religion does not involve political affairs or complex rituals; on the contrary, it encourages the avoidance of public responsibility and the search for a vision of a spiritual transcendent world.

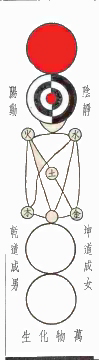

[205][206] Taoists' views about what happens in the afterlife tend to include the soul becoming a part of the cosmos[207] (which was often thought of as an illusionary place where qi and physical matter were thought of as being the same in a way held together by the microcosm of the spirits of the human body and the macrocosm of the universe itself, represented and embodied by the Three Pure Ones),[206] somehow aiding the spiritual functions of nature or Tian after death or being saved by either achieving spiritual immortality in an afterlife or becoming a xian who can appear in the human world at will,[208] but normally lives in another plane.

[213] More specifically, possibilities for "the spirit of the body" include "join[ing] the universe after death",[207] exploring[214] or serving various functions in parts of tiān[215] or other spiritual worlds,[214][216] or becoming a xian who can do one or more of those things.

[41] In the Quanzhen school of Wang Chongyang, the goal is to become a sage, which he equates with being a "spiritual immortal" (shen xien) and with the attainment of "clarity and stillness" (qingjing) through the integration of "inner nature" (xing) and "worldly reality" (ming).

There are various kinds of Taoist rituals, which may include presenting offerings, scripture reading, sacrifices, incantations, purification rites, confession, petitions and announcements to the gods, observing the ethical precepts, memorials, chanting, lectures, and communal feasts.

[301] The earliest manuscripts of this work (written on bamboo tablets) date back to the late 4th century BCE, and these contain significant differences from the later received edition (of Wang Bi c. 226–249).

[304] Louis Komjathy writes that the Tao Te Ching is "actually a multi-vocal anthology consisting of a variety of historical and textual layers; in certain respects, it is a collection of oral teachings of various members of the inner cultivation lineages.

However, some modern scholars, like Russell Kirkland, argue that Guo Xiang is actually the creator of the 33-chapter Zhuangzi text and that there is no solid historical data for the existence of Zhuang Zhou himself (other than the sparse and unreliable mentions in Sima Qian).

They typically feature mystical writing, talismans, or diagrams and are intended to fulfill various functions including providing guidance for the spirits of the dead, bringing good fortune, increasing life span, etc.

[374] Lucretius' poem De rerum natura describes a naturalist cosmology where there are only atoms and void (a primal duality which mirrors yin-yang in its dance of assertion/yielding), and where nature takes its course with no gods or masters.

Other parallels include the similarities between Daoist wu wei (effortless action) and Epicurean lathe biosas (live in obscurity), focus on naturalness (ziran) as opposed to conventional virtues, and the prominence of the Epicurus-like Chinese sage Yang Chu in the foundational Taoist writings.

[397] There are various kinds of festivals in Ceremonial Taoism, including "Great Services" (chai-chiao) and Ritual Gatherings (fa-hui) that can last for days and can focus on repentance, rainmaking, disaster aversion or petitioning.

[409] The Quanzhen School was founded by Wang Chongyang (1112–1170), a hermit in the Zhongnan mountains who was said in legends to have met and learned secret methods from two immortals: Lu Dongbin and Zhongli Quan.

[418] Polytheist Taoists venerated one or more of these kinds of spiritual entities:[419][248] "deified heroes...forces of nature"[248] and "nature spirits",[419] xian,[248] spirits,[248] gods,[248] devas and other celestial beings from Chinese Buddhism, Indian Buddhism, and Chinese folk religion,[248][420][421][422][215] various kinds of beings occupying heaven,[248] members of the celestial bureaucracy,[248] ghosts,[88] "mythical emperors",[423] Laozi,[423] a trinity of high gods that varied in how it was thought of,[248] and the Three Pure Ones.