Free group

An arbitrary group G is called free if it is isomorphic to FS for some subset S of G, that is, if there is a subset S of G such that every element of G can be written in exactly one way as a product of finitely many elements of S and their inverses (disregarding trivial variations such as st = suu−1t).

In an 1882 paper, Walther von Dyck pointed out that these groups have the simplest possible presentations.

[1] The algebraic study of free groups was initiated by Jakob Nielsen in 1924, who gave them their name and established many of their basic properties.

[2][3][4] Max Dehn realized the connection with topology, and obtained the first proof of the full Nielsen–Schreier theorem.

[5] Otto Schreier published an algebraic proof of this result in 1927,[6] and Kurt Reidemeister included a comprehensive treatment of free groups in his 1932 book on combinatorial topology.

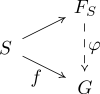

The free group FS is the universal group generated by the set S. This can be formalized by the following universal property: given any function f from S to a group G, there exists a unique homomorphism φ: FS → G making the following diagram commute (where the unnamed mapping denotes the inclusion from S into FS): That is, homomorphisms FS → G are in one-to-one correspondence with functions S → G. For a non-free group, the presence of relations would restrict the possible images of the generators under a homomorphism.

It is known as the universal property of free groups, and the generating set S is called a basis for FS.

Sela (2006) answered the first question by showing that any two nonabelian free groups have the same first-order theory, and Kharlampovich & Myasnikov (2006) answered both questions, showing that this theory is decidable.

A similar unsolved (as of 2011) question in free probability theory asks whether the von Neumann group algebras of any two non-abelian finitely generated free groups are isomorphic.