Operation Sea Lion

Following the Battle of France and that country's capitulation, Adolf Hitler, the German Führer and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, hoped the British government would accept his offer to end the state of war between the two.

[14] Raeder was strongly opposed to Sea Lion, for over half of the Kriegsmarine surface fleet had been either sunk or badly damaged in Weserübung, and his service was hopelessly outnumbered by the ships of the Royal Navy.

[20] To the surprise of Von Brauchitsch and Halder, and completely at odds with his normal practice, Hitler did not ask any questions about specific operations, had no interest in details, and made no recommendations to improve the plans; instead, he simply told OKW to start preparations.

[22][23] Hitler's directive set four conditions for the invasion to occur:[24] This ultimately placed responsibility for Sea Lion's success squarely on the shoulders of Raeder and Göring, neither of whom had the slightest enthusiasm for the venture and, in fact, did little to hide their opposition to it.

[36] This initial plan was vetoed by opposition from both the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe, who successfully argued that an amphibious force could only be assured air and naval protection if confined to a narrow front, and that the landing areas should be as far from Royal Navy bases as possible.

[37] A single airborne division would land in Kent north of Hythe; with the objective of seizing the aerodrome at Lympne and bridge-crossings over the Royal Military Canal, and in assisting the ground forces in capturing Folkestone.

Around 1,300 of the 22nd Air Landing Division had been captured (subsequently shipped to Britain as prisoners of war), around 250 Junkers Ju 52 transport aircraft had been lost, and several hundred elite paratroops and air-landing infantry had been killed or injured.

The Kriegsmarine, already numerically far inferior to Britain's Royal Navy, had lost a sizeable portion of its large modern surface ships in April 1940 during the Norwegian campaign, either as complete losses or due to battle damage.

The idea was first mooted by Generaladmiral Rolf Carls on 1 August proposing a feint expedition into the North Sea resembling a troop convoy heading for Scotland, with the aim of drawing the British Home Fleet away from the intended invasion routes.

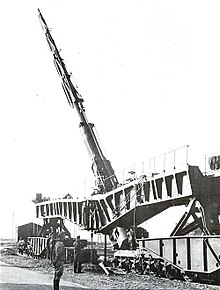

[67] Converting the assembled barges into landing craft involved cutting an opening in the bow for off-loading troops and vehicles, welding longitudinal I-beams and transverse braces to the hull to improve seaworthiness, adding a wooden internal ramp and pouring a concrete floor in the hold to allow for tank transport.

They had the advantage of being able to unload their tanks directly into water up to 15 metres (49 ft) in depth, several hundred yards from shore, whereas the unmodified Type A had to be firmly grounded on the beach, making it more vulnerable to enemy fire.

[70] During the planning stages of Sea Lion, it was deemed desirable to provide the advanced infantry detachments (making the initial landings) with greater protection from small-arms and light artillery fire by lining the sides of a powered Type A barge with concrete.

[72] The Kriegsmarine later used some of the motorised Sea Lion barges for landings on the Russian-held Baltic islands in 1941 and, though most of them were eventually returned to the inland rivers they originally plied, a reserve was kept for military transport duties and for filling out amphibious flotillas.

[80] As part of a Kriegsmarine competition, prototypes for a prefabricated "heavy landing bridge" or jetty (similar in function to later Allied Mulberry Harbours) were designed and built by Krupp Stahlbau and Dortmunder Union and successfully overwintered in the North Sea in 1941–42.

These included: The German Army High Command (Oberkommando des Heeres, OKH) originally planned an invasion on a vast scale, envisioning landing over forty divisions from Dorset to Kent.

With Germany's occupation of the Pas-de-Calais region in northern France, the possibility of closing the Strait of Dover to Royal Navy warships and merchant convoys by the use of land-based heavy artillery became readily apparent, both to the German High Command and to Hitler.

[98] The presence of these batteries was expected to greatly reduce the threat posed by British destroyers and smaller craft along the eastern approaches as the guns would be sited to cover the main transport routes from Dover to Calais and Hastings to Boulogne.

[104] The British prepared extensive defences, and, in Churchill's view, "the great invasion scare" was "serving a most useful purpose" by "keeping every man and woman tuned to a high pitch of readiness".

Author James Hayward has suggested that the whispering campaign around the "failed invasion" was a successful example of British black propaganda to bolster morale at home and in occupied Europe, and convince America that Britain was not a lost cause.

[127] In his history of World War II, Churchill stated, "Had the Germans possessed in 1940 well trained [and equipped] amphibious forces their task would still have been a forlorn hope in the face of our sea and air power.

Andrew Gordon, in an article for the Royal United Services Institute Journal[132] agrees with this and is clear in his conclusion the German Navy was never in a position to mount Sealion, regardless of any realistic outcome of the Battle of Britain.

His assessment concurs with that emerging from the 1974 Sandhurst Sea Lion wargame (see below) that the first wave would likely have crossed the Channel and established a lodgement around the landing beaches in Kent and East Sussex without major loss, and that the defending British forces would have been unlikely to have dislodged them once ashore.

[141] British intelligence further calculated that Folkestone, the largest harbour falling within the planned German landing zones, could handle 150 tons per day in the first week of the invasion (assuming all dockside equipment was successfully demolished and regular RAF bombing raids reduced capacity by 50%).

This meant that, at best, the nine German infantry and one airborne division landed in the first wave would receive less than 20% of the 3,300 tons of supplies they required each day through a port and would have to rely heavily on whatever could be brought in directly over the beaches or air-lifted into captured airstrips.

However, this rested on the rather unrealistic assumption of little or no interference from the Royal Navy and RAF with the German supply convoys which would have been made up of underpowered (or unpowered, i.e., towed) inland waterways vessels as they shuttled slowly between the Continent to the invasion beaches and any captured harbours.

[151][153] The continued military actions against the UK after the fall of France had the strategic goal of making Britain 'see the light' and conduct an armistice with the Axis powers, with 1 July 1940 being named the "probable date" for the cessation of hostilities.

The remaining population would have been terrorised, including civilian hostages being taken and the death penalty immediately imposed for even the most trivial acts of resistance, with the UK being plundered for anything of financial, military, industrial or cultural value.

[160] According to the most detailed plans created for the immediate post-invasion administration, Great Britain and Ireland were to be divided into six military-economic commands, with headquarters in London, Birmingham, Newcastle, Liverpool, Glasgow and Dublin.

[167] The German Government used 90% of James Vincent Murphy's rough draft translation of Mein Kampf to form the body of an edition to be distributed in the UK once Operation Sea Lion was completed.

[170] Had Operation Sea Lion succeeded, Franz Six was intended to become the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) Commander in the country, with his headquarters to be located in London, and with regional task forces in Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, and Edinburgh.