Tea culture in Japan

Eisai then lists tea's many supposed health benefits: dispelling fatigue, curing lupus, indigestion, beriberi, cardiovascular disease, and many others, in addition to its hydrating effect.

[21] This type of gathering is described in the Treatise on Tea Tasting (Kissa ōrai) attributed to the monk Gen'e (1279–1350), which begins as soon as guests arrive at the host's residence, facing a strolling garden, where a first snack is offered.

At the time, this was an exclusively male audience, drawn from the wealthy circles of Kyoto and the major trading cities (Sakai, Hakata) that had been won over by the art of tea.

During the Sengoku period, political and social structures evolved very rapidly:[34] although the son of a Sakai fishmonger, Rikyū was able to study tea with Takeno Jōō and, like his mentor, was inspired by the wabi style.

According to the description left by the German Engelbert Kaempfer, who lived in Japan at the end of the 17th century, green tea is made locally using the Chinese method of dry cooking in a wok.

Some became establishments providing various types of entertainment: sumojaya specialized in sumo fights, shibaijaya in theatrical performances; in pleasure districts, mijuzaya where male customers were served tea and sake by young women, and hikitejaya which acted as brothels.

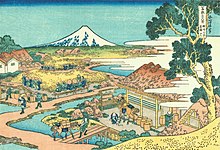

[60][63] Since the 16th century, there is documented evidence of the practice of laying rice straw mats over tea plantations in Uji to protect them from the volcanic ash spewed by Mount Fuji.

It was later found that this shading altered the taste of the teas, resulting in a beverage deemed to be of better quality, and the practice spread to other terroirs, being used to make renowned varieties of matcha, gyokuro and kabusecha.

The traditional form of these shades consisted of trellises of reeds or rice straw resting on bamboo structures erected over the plantations, and nowadays coverings are made of artificial cloth.

[68] This mechanization explains the appearance of Japanese tea fields, in which the bushes are pruned into a rounded shape and spaced at very regular intervals to facilitate the passage of machinery.

[70] The specific processing method developed in the eighteenth century involves stopping oxidation of the leaves by steaming, for varying lengths of time depending on the quality required (from 30 sec.

These are mature leaves, thicker and harder, which have been exposed to the summer sun, and the later ones are plucked from the lower parts of the tea plant that have been spared by the first harvests, so are roughly trimmed and rarely whole.

The traditional method was done in a wok or heated bowl, but higher-capacity automated cooking and rolling machines have been developed to increase the production capacity of this tea, previously produced in small quantities.

Japanese Black tea, produced from leaves whose oxidation has been prolonged to completion, is a marginal product in Japan in the 2010s, even though it has a long history since it was first developed in the second half of the 19th century for export purposes.

Nevertheless, since the beginning of the 21st century, Japanese black tea (known as wakoucha) production has picked up again to meet renewed domestic demand (under Western influence), reaching around 200 tonnes in 2016.

[42] Several of these houses still exist and are major players in the sector, belonging to the category of Japanese companies known as shinise, whose operations have been passed down within the same family, sometimes for many generations, many of them having been founded in the 19th century: in Uji, for example, Tsuen and Kanbayashi; in Kyoto, Fukujuen and Ippodo.

[94] The boom in tea beverages subsequently forced the archipelago's manufacturers to import raw leaves at a high level, as domestic production could not meet their demand, but it gradually adjusted.

Furthermore, the Japanese invested in nearby countries such as China, Indonesia, and Vietnam to produce Japanese-style sencha teas, as domestic production was insufficient to cover demand.

It gradually appeared during the second half of the medieval period, starting with tea-drinking gatherings, the proceedings of which were formalized by a series of tea masters strongly influenced by Zen Buddhism, notably Murata Jukō (1422–1502), Takeno Jōō (1502–1555) and Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591).

A ceremonial style was established, marked by the consumption of whipped tea and a meal (kaiseki), and incorporating the principles of wabi (侘び), the pursuit of elegance in simplicity and tranquility, and sabi (寂), a nostalgic contemplation of the passage of time that valued objects with an aged, rustic character.

The monk Baisaō popularized the beverage, promoting a free and simple approach (all one had to do was brew the sencha leaves before consuming the drink), in contrast to the extreme formalism of the tea ceremony of his time.

The "way of the sencha" (煎茶道, senchadō), later formalized, proposed a simpler aesthetic and freer ritual compared to that of the tea ceremony, even though its precepts brought it closer to its competitor.

As early as the 14th century, when tea was still relatively unknown in Japanese society, it was offered to Buddha during religious ceremonies; today, this type of ritual still exists, such as the Ochamori at Saidai-ji in Nara.

For the more elaborate forms of leaf tea consumption, generally using better-quality leaves (sencha, gyokuro or tamaryokucha), a ceramic pot is used, consisting of at least cups and the small (usually 36 cl, sometimes less) earthenware porcelain teapot or pan known as a kyusū.

The early tea masters who laid the foundations of this art paid great attention to the choice of objects used, which had to correspond to the general aesthetic framework of the ritual.

[116] Tea aficionados, and Japanese aesthetes in general, have long attached great importance to objects and fine manual production, with traditional craft arts seen as a national heritage.

Great attention is paid to fireplace frames (robuchi), meal trays (shokuro), incense boxes (kōgō), cold water containers (mizusashi) and tea caddies (natsume).

Ceramics have long been the major art form for the tea ceremony, produced in the same workshops since late medieval times (Bizen, Mino), although processes have generally been modernized, even if some ceramists use kilns crafted according to ancient methods.

Of course, this isn't totally new, as ochazuke, which is based on green tea poured into a bowl of rice to which other ingredients can be added, has long been a well-known recipe in Japanese cuisine.

Ice creams, pastries, and other sweet treats made with matcha have thus become very common in Japan and elsewhere, as has its use in popular drinks such as milkshakes, lattes, alcoholic and non-alcoholic cocktails, etc., all taking advantage of the fact that green tea is often promoted for its health benefits.